You Were Created to Be Silent

When G-d Speaks, a Universe is Created; When G-d Thinks, a Soul is Created

- May 31, 2012

- |

- 10 Sivan 5772

Rabbi YY Jacobson

816 views

You Were Created to Be Silent

When G-d Speaks, a Universe is Created; When G-d Thinks, a Soul is Created

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 31, 2012

The Silent Parrot

An old Jew received a parrot from his sons after his wife died, to keep him company. He discovered that the parrot had heard him pray so often, that it had learned to say the prayers. The old man was so thrilled, that he decided to take his parrot to the synagogue on Rosh Hashana (the Jewish new year). When he entered with the bird, the rabbi tried to protest, but when he told him the parrot could pray ("daven" in Yiddish), the rabbi showed interest, though still skeptical. People started betting on whether the parrot would pray, and the old man happily took all the bets that went up to $50,000.

The prayer starts – but the bird is silent. The prayer continues - not a word from the bird. The prayer ends, and the old man, crestfallen, is now in debt $50,000 for all of the bets. On the way home he thunders at his parrot: "Why did you do this to me? I know you can pray, you know you can pray, why did you keep your mouth shut? Do you know how much money I owe people now?"

To which the parrot replied: "A little business imagination would help you, dear friend. You must look ahead: Can you imagine what the stakes will be like on Yom Kippur?"

The Purpose of Life

“Rabbai Gamliel’s son, Shimon, would say: All my life I have been raised among the wise, and I have found nothing better for the body than silence.”

-- Ethics of the Fathers, 1:17 (chapter of this week.)

What is the meaning of these words? Why is there nothing better for the body than silence? And why the emphasis on the body, more than on the general person (“I have found nothing better for the person…”).

Silence is certainly a positive quality in life, especially in particular instances. But is really nothing better for the human body than silence?

The Talmud goes even further, stating a deeply enigmatic statement[1]: “What is man’s task in the world? To make himself as silent as the dumb.”

Surely, silence is not always a bad idea, especially for certain types of people. But is this really man’s task in the world? Were we created merely to be silent? Does the Talmud believe that the entire purpose of our creation was to keep our mouths shut?

A Thing of Silence

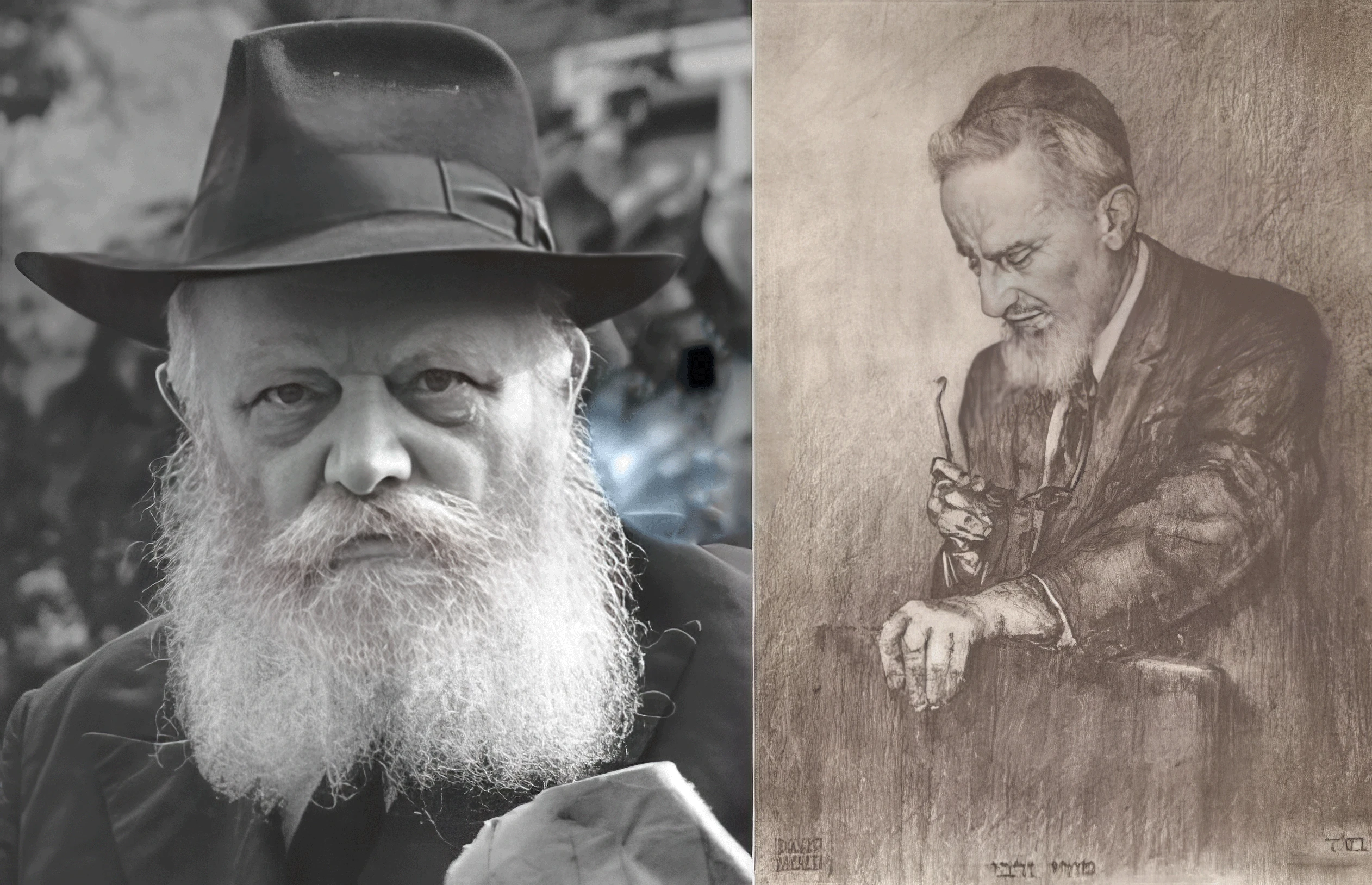

In a brilliant exposition, the Lubavitcher Rebbe once presented the following interpretation[2].

The Torah defines all of existence as G-d’s speech. As Genesis puts it: “G-d said: ‘Let there be light!’ and there was light.” G-d said: “May the earth sprout forth vegetation,” etc.

Why does Torah employ the metaphor of speech to define the process of creation? Because in speech – unlike thought – the words of the speaker leave his or her domain and travel into a world outside of the speaker. When a person thinks, the ideas exist only within his or her own mind; when the thought is translated into words, it departs the person’s inner world, to attain an existence distinct from his.

This is why creation is described as G-d’s speech: G-d created a world which though completely dependent on Him (like words on the speaker), and continuously sustained by Him, nevertheless perceives itself as distinct and separate from G-d. In our world, one can remain completely oblivious to G-d and to any deeper reality pervading existence. One can enjoy the status of “agnostic” or “atheist,” walk our planet for ninety years and not even once entertain the idea that the presence of the living G-d vibrates through every moment of consciousness and every being. G-d “spoke” us into existence and thus allowed us to experience ourselves as “outside” and detached from His reality.

There is, however, a single exception to this model for the essential nature of all created things: the soul of man. The soul, the Neshamah, is described in Torah and Kabbalah[3] not as a Divine word but as a G-dly thought.

Why the metaphor of thought? Just as a thought never departs from the inner domain of the thinker, the soul, too, is a creation which never “departs” from the all-pervading reality of G-d. Unlike the rest of the world which experiences itself as an egotistical reality, separate from the Divine, the soul experiences itself as submerged in the cosmic oneness of reality, and never sees itself as an “entity” distinct from its Creator.

When G-d speaks, a universe is created. When G-d thinks, a soul is created.

Alone in a verbose world, the soul of man is a “thing of silence.” And its mission in life is to impart this silence to the world about it.

We were created to share the “silence” of the soul with the rest of the world, beginning with our own bodies.

[1] Talmud, Chulin 89a.

[2] The Lubavitcher Rebbe communicated this idea during an address on Shabbos Parshas Acharei Mos, 24 Nissan, 5719 (May 2, 1959), published in Likkutei Sichos vol. 4 Avos ch. 1. Cf. the rendition of Rabbo Yanki Tauber of this talk at http://meaningfullife.com/torah/ethics/1/The_Soul_COLON_A_Thing_of_Silence.php

[3] Zohar part II p. 119a; Ohr Torah (by Rabbi DovBer the Maggid of Mezeritch) 2c; Tanya Chapter 2.

- Comment

Class Summary:

With much appreciation and respect

The Silent Parrot

An old Jew received a parrot from his sons after his wife died, to keep him company. He discovered that the parrot had heard him pray so often, that it had learned to say the prayers. The old man was so thrilled, that he decided to take his parrot to the synagogue on Rosh Hashana (the Jewish new year). When he entered with the bird, the rabbi tried to protest, but when he told him the parrot could pray ("daven" in Yiddish), the rabbi showed interest, though still skeptical. People started betting on whether the parrot would pray, and the old man happily took all the bets that went up to $50,000.

The prayer starts – but the bird is silent. The prayer continues - not a word from the bird. The prayer ends, and the old man, crestfallen, is now in debt $50,000 for all of the bets. On the way home he thunders at his parrot: "Why did you do this to me? I know you can pray, you know you can pray, why did you keep your mouth shut? Do you know how much money I owe people now?"

To which the parrot replied: "A little business imagination would help you, dear friend. You must look ahead: Can you imagine what the stakes will be like on Yom Kippur?"

The Purpose of Life

“Rabbai Gamliel’s son, Shimon, would say: All my life I have been raised among the wise, and I have found nothing better for the body than silence.”

-- Ethics of the Fathers, 1:17 (chapter of this week.)

What is the meaning of these words? Why is there nothing better for the body than silence? And why the emphasis on the body, more than on the general person (“I have found nothing better for the person…”).

Silence is certainly a positive quality in life, especially in particular instances. But is really nothing better for the human body than silence?

The Talmud goes even further, stating a deeply enigmatic statement[1]: “What is man’s task in the world? To make himself as silent as the dumb.”

Surely, silence is not always a bad idea, especially for certain types of people. But is this really man’s task in the world? Were we created merely to be silent? Does the Talmud believe that the entire purpose of our creation was to keep our mouths shut?

A Thing of Silence

In a brilliant exposition, the Lubavitcher Rebbe once presented the following interpretation[2].

The Torah defines all of existence as G-d’s speech. As Genesis puts it: “G-d said: ‘Let there be light!’ and there was light.” G-d said: “May the earth sprout forth vegetation,” etc.

Why does Torah employ the metaphor of speech to define the process of creation? Because in speech – unlike thought – the words of the speaker leave his or her domain and travel into a world outside of the speaker. When a person thinks, the ideas exist only within his or her own mind; when the thought is translated into words, it departs the person’s inner world, to attain an existence distinct from his.

This is why creation is described as G-d’s speech: G-d created a world which though completely dependent on Him (like words on the speaker), and continuously sustained by Him, nevertheless perceives itself as distinct and separate from G-d. In our world, one can remain completely oblivious to G-d and to any deeper reality pervading existence. One can enjoy the status of “agnostic” or “atheist,” walk our planet for ninety years and not even once entertain the idea that the presence of the living G-d vibrates through every moment of consciousness and every being. G-d “spoke” us into existence and thus allowed us to experience ourselves as “outside” and detached from His reality.

There is, however, a single exception to this model for the essential nature of all created things: the soul of man. The soul, the Neshamah, is described in Torah and Kabbalah[3] not as a Divine word but as a G-dly thought.

Why the metaphor of thought? Just as a thought never departs from the inner domain of the thinker, the soul, too, is a creation which never “departs” from the all-pervading reality of G-d. Unlike the rest of the world which experiences itself as an egotistical reality, separate from the Divine, the soul experiences itself as submerged in the cosmic oneness of reality, and never sees itself as an “entity” distinct from its Creator.

When G-d speaks, a universe is created. When G-d thinks, a soul is created.

Alone in a verbose world, the soul of man is a “thing of silence.” And its mission in life is to impart this silence to the world about it.

We were created to share the “silence” of the soul with the rest of the world, beginning with our own bodies.

[1] Talmud, Chulin 89a.

[2] The Lubavitcher Rebbe communicated this idea during an address on Shabbos Parshas Acharei Mos, 24 Nissan, 5719 (May 2, 1959), published in Likkutei Sichos vol. 4 Avos ch. 1. Cf. the rendition of Rabbo Yanki Tauber of this talk at http://meaningfullife.com/torah/ethics/1/The_Soul_COLON_A_Thing_of_Silence.php

[3] Zohar part II p. 119a; Ohr Torah (by Rabbi DovBer the Maggid of Mezeritch) 2c; Tanya Chapter 2.

Tags

Categories

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 31, 2012

- |

- 10 Sivan 5772

- |

- 816 views

You Were Created to Be Silent

When G-d Speaks, a Universe is Created; When G-d Thinks, a Soul is Created

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 31, 2012

The Silent Parrot

An old Jew received a parrot from his sons after his wife died, to keep him company. He discovered that the parrot had heard him pray so often, that it had learned to say the prayers. The old man was so thrilled, that he decided to take his parrot to the synagogue on Rosh Hashana (the Jewish new year). When he entered with the bird, the rabbi tried to protest, but when he told him the parrot could pray ("daven" in Yiddish), the rabbi showed interest, though still skeptical. People started betting on whether the parrot would pray, and the old man happily took all the bets that went up to $50,000.

The prayer starts – but the bird is silent. The prayer continues - not a word from the bird. The prayer ends, and the old man, crestfallen, is now in debt $50,000 for all of the bets. On the way home he thunders at his parrot: "Why did you do this to me? I know you can pray, you know you can pray, why did you keep your mouth shut? Do you know how much money I owe people now?"

To which the parrot replied: "A little business imagination would help you, dear friend. You must look ahead: Can you imagine what the stakes will be like on Yom Kippur?"

The Purpose of Life

“Rabbai Gamliel’s son, Shimon, would say: All my life I have been raised among the wise, and I have found nothing better for the body than silence.”

-- Ethics of the Fathers, 1:17 (chapter of this week.)

What is the meaning of these words? Why is there nothing better for the body than silence? And why the emphasis on the body, more than on the general person (“I have found nothing better for the person…”).

Silence is certainly a positive quality in life, especially in particular instances. But is really nothing better for the human body than silence?

The Talmud goes even further, stating a deeply enigmatic statement[1]: “What is man’s task in the world? To make himself as silent as the dumb.”

Surely, silence is not always a bad idea, especially for certain types of people. But is this really man’s task in the world? Were we created merely to be silent? Does the Talmud believe that the entire purpose of our creation was to keep our mouths shut?

A Thing of Silence

In a brilliant exposition, the Lubavitcher Rebbe once presented the following interpretation[2].

The Torah defines all of existence as G-d’s speech. As Genesis puts it: “G-d said: ‘Let there be light!’ and there was light.” G-d said: “May the earth sprout forth vegetation,” etc.

Why does Torah employ the metaphor of speech to define the process of creation? Because in speech – unlike thought – the words of the speaker leave his or her domain and travel into a world outside of the speaker. When a person thinks, the ideas exist only within his or her own mind; when the thought is translated into words, it departs the person’s inner world, to attain an existence distinct from his.

This is why creation is described as G-d’s speech: G-d created a world which though completely dependent on Him (like words on the speaker), and continuously sustained by Him, nevertheless perceives itself as distinct and separate from G-d. In our world, one can remain completely oblivious to G-d and to any deeper reality pervading existence. One can enjoy the status of “agnostic” or “atheist,” walk our planet for ninety years and not even once entertain the idea that the presence of the living G-d vibrates through every moment of consciousness and every being. G-d “spoke” us into existence and thus allowed us to experience ourselves as “outside” and detached from His reality.

There is, however, a single exception to this model for the essential nature of all created things: the soul of man. The soul, the Neshamah, is described in Torah and Kabbalah[3] not as a Divine word but as a G-dly thought.

Why the metaphor of thought? Just as a thought never departs from the inner domain of the thinker, the soul, too, is a creation which never “departs” from the all-pervading reality of G-d. Unlike the rest of the world which experiences itself as an egotistical reality, separate from the Divine, the soul experiences itself as submerged in the cosmic oneness of reality, and never sees itself as an “entity” distinct from its Creator.

When G-d speaks, a universe is created. When G-d thinks, a soul is created.

Alone in a verbose world, the soul of man is a “thing of silence.” And its mission in life is to impart this silence to the world about it.

We were created to share the “silence” of the soul with the rest of the world, beginning with our own bodies.

[1] Talmud, Chulin 89a.

[2] The Lubavitcher Rebbe communicated this idea during an address on Shabbos Parshas Acharei Mos, 24 Nissan, 5719 (May 2, 1959), published in Likkutei Sichos vol. 4 Avos ch. 1. Cf. the rendition of Rabbo Yanki Tauber of this talk at http://meaningfullife.com/torah/ethics/1/The_Soul_COLON_A_Thing_of_Silence.php

[3] Zohar part II p. 119a; Ohr Torah (by Rabbi DovBer the Maggid of Mezeritch) 2c; Tanya Chapter 2.

- Comment

With much appreciation and respect

Class Summary:

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!