The Legacy of Woodstock

When the youth loses sight of the difference between right and wrong, a new opportunity is born

- August 31, 2009

- |

- 11 Elul 5769

Rabbi YY Jacobson

1266 views

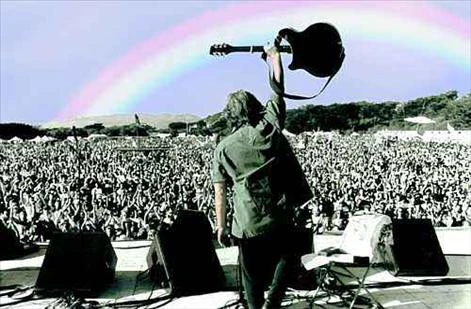

Woodstock, August 1969

The Legacy of Woodstock

When the youth loses sight of the difference between right and wrong, a new opportunity is born

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- August 31, 2009

Forty years ago, when America watched news reports from Woodstock, the youthful counter-culture saw a celebration of their generation. But many of their elders saw an unimaginable horde of immoral, drug-abusing, morally unrestrained freaks.

The rebellion of the youth of the 60’s culminated with what has become a cultural symbol - the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in August of '69 that drew close to a half million people to a pasture in Sullivan County, N.Y. For four days the pilgrims experimented with extraordinary quantities of drugs, "free" love, and minds and hearts open to anything and everything. The music, which began Friday afternoon, Aug. 15 and continued until mid-morning of Monday, Aug. 18, captured the wild life of the flower generation, as their teachers and parents looked on in shock, grief, awe or a combination of the three.Why did an entire generation of young and bright Americans reject the pragmatic and sensible path of their parents and grandparents? Was it an expression of immature naiveté and futile innocence? Was it simply one hell of a party, legitimizing hedonistic temptations? Was it merely a holiday of dumb luck before the realities of capitalism resumed? Was Woodstock a whole lot of people getting stoned at a rock concert, which was much easier than working to change the world?Or was there something deeper at stake?The Lubavitcher Rebbe (1902-1994), one of the great moral voices of that generation, in a historical address six months after the event, Purim 1970, saw it as something far more profound and existential than just lots of youngsters living out their natural animal passions *.A little introduction is necessary.DrunkAn intriguing and uncharacteristic statement in the Talmud (the primary body of Jewish law and literature) declares that "On Purim a person is obligated to become intoxicated until he does not know the difference between 'Cursed is Haman' and 'Blessed is Mordechai.'" (Talmud, Megilah 7b).

In Judaism, excessive drinking is seen as both repulsive and destructive. In Genesis we are informed that intoxication by Noah and then Lot led to disaster. Little needs to be said today to validate this truth. In America today, as in so many other parts of the world, alcoholism has destroyed too many a life and family. For people who have fallen prey to the devil of addiction, no religious excuse should ever be employed to allow the horrible demon of alcoholic or drug addiction to destroy themselves and their loved ones.

Yet for individuals living up to Talmudic moral and spiritual standards - abstaining from any form of excessive drinking all year around and, instead, toiling to refine their characters and dispositions under complete sobriety -- Jewish tradition designates one day of the year when they ought to leave the inhibitions of the rational mind in order to express the depth and glow of their passions, which are usually stored in the super-conscious chambers of their souls. An individual who has dedicated an entire year to work soberly on his or her psychological, emotional and spiritual identity, as Judaism incessantly demands, is highly unlikely to be pulled down by the once-a-year consumption of alcohol.

Still, the Talmud's demand that under the spell of intoxication one ought to forget the difference between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" seems absolutely bizarre.

Haman was a ruthless power monger, a self-centered egomaniac and an evil barbarian who schemed to exterminate every single Jew living in the Persian Empire. He was the Hitler of his day. Mordechai, on the other hand, was a saintly sage, a genuine leader, a lover of G-d, of his people and of humanity. It seems obvious that a decent human being should never forget that Haman must be cursed and Mordechai blessed. Moral equations between monsters and good people, although popular in some academic circles today, are grotesque and disgusting. They allow the monsters to continue their work.

What is even more bizarre is that we are enjoined to engage in this forgetfulness on the Jewish holiday of Purim - the day in which we celebrate Jewish deliverance from the vicious Haman as a result of the courageous spiritual and political leadership of Mordechai. The very holiday of Purim is about the fall of Haman and the rise of Mordechai. How, then, are we to make sense of the Talmud's demand that on Purim we know not "the difference between 'Cursed is Haman' and 'Blessed is Mordechai' when this distinction is what constitutes the very essence and purpose of the holiday!

Obviously, then, we must understand these words of the Talmud in a deeper way. Indeed, interpretations are abundant. What follows is one of my personal favorites presented by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, delivered at that Purim assembly in 1970, some six months after Woodstock.

Why Should I Be a Good Person?

There are two levels of consciousness, the Rebbe explained, in which one can distinguish between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai." The first is pragmatic and materialistic; the second is soulful and eternal. One speaks in the name of self-interest and personal gain, the other in the name of meaning.

From a pragmatic and materialistic world outlook, Haman's path ought to be rejected, and Mordechai's lifestyle embraced. Indeed, many of our parents and grandparents employed the pragmatic argument in order to persuade us to live the good and decent life.

"If you wish to get into a good college," they told us, "you should keep away from drugs and alcohol. If you want to graduate with honors, you must abstain from promiscuity and frivolousness. If you desire to be hired by a successful firm or company, you need to demonstrate responsibility, consistency and trust and get a good education. If you want to generate a good income, live in a beautiful home, take a few vacations a year, and own three cars and a summer home, you need to get up early each morning, put in a full day at the office, remain loyal to your spouse and stay away from dangerous and trippy behavior. If you wish to be respected socially and invited to upper-class receptions, stay away from any form of racism, bigotry and violence. You must behave like a 'mentch.'

"And," they continued, "if you manage to give some charity on the side, you might even be honored one day at fund-raising dinners and have your name engraved on a building or two. When you hit old age, you will retire with dignity, accompanied by a hefty savings account and time for golf and relaxation. If you make enough money, you may even establish a tax-deductible foundation on your name."

This is, admittedly, a nice vision (a certain part of me likes it too, though I must confess I have at this stage of my life already violated many of the ground rules.) It promotes decent behavior, loyal citizenship, hard work and faithful family commitments. It works for many youngsters and has proven successful with many American Jews who made a life for themselves. Yet it proved futile with millions of American and Jewish youngsters who in the 1960s revolted against the "Establishment" and embraced a lifestyle of boundless frivolousness, uninhibited intimacy and uncontrolled acid trips.

In the view of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, large segments of American youth were consciously or subconsciously rejecting the pragmatic but essentially self-serving philosophy of their teachers and parents because it failed to address the depth of their souls. It spoke in the name of financial security, comfortable living and a respectable social status. It attempted to impress them with the glamour of a comfortable life style, a nice home, beautiful clothes and engaging entertainment.

These are certainly tempting to many of us. But what about the idealistic cords inherent in the soul of our youth? What about the passion for truth and the dedication emblematic of the human spirit? What about human beings' quest to touch infinity and live a life of true meaning? On this count the Establishment failed them miserably then, as it does so often now. Not because it demanded too much, but because it expected too little. It reduced souls to machines, spirits to robots and humans capable of moral greatness to self-centered creatures. It spoke not to the profoundest passions of our youngsters but rather to their most superficial instincts. It addressed not their idealistic and spiritual yearnings, only their bodies and physical cravings.“We are not only animals,” was the subconscious cry of a generation, “searching for self gratification and self aggrandizement. We are souls; we care not only about a capitalistic secure financial future, but for deep meaning and the echo of truth.”

When the distinction between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" is founded merely on materialistic, self-serving and pragmatic benefits rather than on the deepest passions and commitments of the human soul; when it speaks in the name of external satisfaction rather than with the voice of existential wholesomeness, the youthful spirit is likely to reject it and, in his or her rebelliousness, travel to the opposite extreme where the distinctions between Haman and Mordechai are blurred and all moral standards become hazy and meaningless.When the goals of education and decent behavior are motivated by superficial human qualities they do not resonate with deeper, more sensitive and more spiritual kids. And in their attempt to touch their own depth, they reject all standards and boundaries.Shattering the Myth

This is the meaning behind the Talmud's demand that on Purim we must lose our knowledge of the distinction between Haman's evil and Mordechai's goodness. There is no question that even on Purim we must know the difference between good and evil, between light and darkness, between love and hate, between a life committed to building the world and a life dedicated to destroying it. Never are we permitted to forget the difference between a lifestyle of morality and virtue vs. a lifestyle of immorality and selfishness.

What the Talmud is telling us, however, is that for the distinction between the two to resonate deeply and eternally, sometimes the superficial basis for the distinction between the two paths of life must first be destroyed. It is only after we know not the difference between Haman and Mordechai on a superficial level – because we are not driven merely by our selfish instincts and motivations -- that we can discover the essential difference on a far truer and deeper level.And this, the Rebbe concluded, was the true calling behind the rebelliousness of the youth. They were rejecting the superficial distinctions between “Haman” and “Mordechai,” because these did not resonate with their deep, sensitive souls. Morality must speak in the name of truth and depth, not in the name of shallow narcissistic benefits. “Don’t blame the youth, blame the educators,” the Rebbe declared.Now, he believed, we have the opportunity to teach the youth about the true and profound distinctions between the two lifestyles and philosophies, founded on the soul's awareness that man was created to become larger than human, and that in a life committed to goodness, kindness, morality and the service of G-d the soul encounters itself in its profoundest dreams, tragedies and hopes.

And Today...

Forty years have passed. Woodstock today is nostalgia. And even nostalgia today is not what it used to be like, as one old nostalgic man remarked.Yet so many youth still find themselves in the muddy fields of unrestrained passion and behavior. Are they too not responding to the superficial messages coming from their teaches and parents?*) The Lubavitcher Rebbe, in his usual style of avoiding direct references, did not mention Woodstock by name, only an entire generation of young people who rejected the Establishment.- Comment

Class Summary:

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein

In honor of their new-born nephew Menachem Mendel Schottenstein

Forty years ago, when America watched news reports from Woodstock, the youthful counter-culture saw a celebration of their generation. But many of their elders saw an unimaginable horde of immoral, drug-abusing, morally unrestrained freaks.

In Judaism, excessive drinking is seen as both repulsive and destructive. In Genesis we are informed that intoxication by Noah and then Lot led to disaster. Little needs to be said today to validate this truth. In America today, as in so many other parts of the world, alcoholism has destroyed too many a life and family. For people who have fallen prey to the devil of addiction, no religious excuse should ever be employed to allow the horrible demon of alcoholic or drug addiction to destroy themselves and their loved ones.

Yet for individuals living up to Talmudic moral and spiritual standards - abstaining from any form of excessive drinking all year around and, instead, toiling to refine their characters and dispositions under complete sobriety -- Jewish tradition designates one day of the year when they ought to leave the inhibitions of the rational mind in order to express the depth and glow of their passions, which are usually stored in the super-conscious chambers of their souls. An individual who has dedicated an entire year to work soberly on his or her psychological, emotional and spiritual identity, as Judaism incessantly demands, is highly unlikely to be pulled down by the once-a-year consumption of alcohol.

Still, the Talmud's demand that under the spell of intoxication one ought to forget the difference between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" seems absolutely bizarre.

Haman was a ruthless power monger, a self-centered egomaniac and an evil barbarian who schemed to exterminate every single Jew living in the Persian Empire. He was the Hitler of his day. Mordechai, on the other hand, was a saintly sage, a genuine leader, a lover of G-d, of his people and of humanity. It seems obvious that a decent human being should never forget that Haman must be cursed and Mordechai blessed. Moral equations between monsters and good people, although popular in some academic circles today, are grotesque and disgusting. They allow the monsters to continue their work.

What is even more bizarre is that we are enjoined to engage in this forgetfulness on the Jewish holiday of Purim - the day in which we celebrate Jewish deliverance from the vicious Haman as a result of the courageous spiritual and political leadership of Mordechai. The very holiday of Purim is about the fall of Haman and the rise of Mordechai. How, then, are we to make sense of the Talmud's demand that on Purim we know not "the difference between 'Cursed is Haman' and 'Blessed is Mordechai' when this distinction is what constitutes the very essence and purpose of the holiday!

Obviously, then, we must understand these words of the Talmud in a deeper way. Indeed, interpretations are abundant. What follows is one of my personal favorites presented by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, delivered at that Purim assembly in 1970, some six months after Woodstock.

There are two levels of consciousness, the Rebbe explained, in which one can distinguish between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai." The first is pragmatic and materialistic; the second is soulful and eternal. One speaks in the name of self-interest and personal gain, the other in the name of meaning.

From a pragmatic and materialistic world outlook, Haman's path ought to be rejected, and Mordechai's lifestyle embraced. Indeed, many of our parents and grandparents employed the pragmatic argument in order to persuade us to live the good and decent life.

"If you wish to get into a good college," they told us, "you should keep away from drugs and alcohol. If you want to graduate with honors, you must abstain from promiscuity and frivolousness. If you desire to be hired by a successful firm or company, you need to demonstrate responsibility, consistency and trust and get a good education. If you want to generate a good income, live in a beautiful home, take a few vacations a year, and own three cars and a summer home, you need to get up early each morning, put in a full day at the office, remain loyal to your spouse and stay away from dangerous and trippy behavior. If you wish to be respected socially and invited to upper-class receptions, stay away from any form of racism, bigotry and violence. You must behave like a 'mentch.'

"And," they continued, "if you manage to give some charity on the side, you might even be honored one day at fund-raising dinners and have your name engraved on a building or two. When you hit old age, you will retire with dignity, accompanied by a hefty savings account and time for golf and relaxation. If you make enough money, you may even establish a tax-deductible foundation on your name."

This is, admittedly, a nice vision (a certain part of me likes it too, though I must confess I have at this stage of my life already violated many of the ground rules.) It promotes decent behavior, loyal citizenship, hard work and faithful family commitments. It works for many youngsters and has proven successful with many American Jews who made a life for themselves. Yet it proved futile with millions of American and Jewish youngsters who in the 1960s revolted against the "Establishment" and embraced a lifestyle of boundless frivolousness, uninhibited intimacy and uncontrolled acid trips.

These are certainly tempting to many of us. But what about the idealistic cords inherent in the soul of our youth? What about the passion for truth and the dedication emblematic of the human spirit? What about human beings' quest to touch infinity and live a life of true meaning? On this count the Establishment failed them miserably then, as it does so often now. Not because it demanded too much, but because it expected too little. It reduced souls to machines, spirits to robots and humans capable of moral greatness to self-centered creatures. It spoke not to the profoundest passions of our youngsters but rather to their most superficial instincts. It addressed not their idealistic and spiritual yearnings, only their bodies and physical cravings.

When the distinction between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" is founded merely on materialistic, self-serving and pragmatic benefits rather than on the deepest passions and commitments of the human soul; when it speaks in the name of external satisfaction rather than with the voice of existential wholesomeness, the youthful spirit is likely to reject it and, in his or her rebelliousness, travel to the opposite extreme where the distinctions between Haman and Mordechai are blurred and all moral standards become hazy and meaningless.

What the Talmud is telling us, however, is that for the distinction between the two to resonate deeply and eternally, sometimes the superficial basis for the distinction between the two paths of life must first be destroyed. It is only after we know not the difference between Haman and Mordechai on a superficial level – because we are not driven merely by our selfish instincts and motivations -- that we can discover the essential difference on a far truer and deeper level.

And Today...

Forty years have passed. Woodstock today is nostalgia. And even nostalgia today is not what it used to be like, as one old nostalgic man remarked.

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- August 31, 2009

- |

- 11 Elul 5769

- |

- 1266 views

The Legacy of Woodstock

When the youth loses sight of the difference between right and wrong, a new opportunity is born

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- August 31, 2009

Forty years ago, when America watched news reports from Woodstock, the youthful counter-culture saw a celebration of their generation. But many of their elders saw an unimaginable horde of immoral, drug-abusing, morally unrestrained freaks.

The rebellion of the youth of the 60’s culminated with what has become a cultural symbol - the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in August of '69 that drew close to a half million people to a pasture in Sullivan County, N.Y. For four days the pilgrims experimented with extraordinary quantities of drugs, "free" love, and minds and hearts open to anything and everything. The music, which began Friday afternoon, Aug. 15 and continued until mid-morning of Monday, Aug. 18, captured the wild life of the flower generation, as their teachers and parents looked on in shock, grief, awe or a combination of the three.Why did an entire generation of young and bright Americans reject the pragmatic and sensible path of their parents and grandparents? Was it an expression of immature naiveté and futile innocence? Was it simply one hell of a party, legitimizing hedonistic temptations? Was it merely a holiday of dumb luck before the realities of capitalism resumed? Was Woodstock a whole lot of people getting stoned at a rock concert, which was much easier than working to change the world?Or was there something deeper at stake?The Lubavitcher Rebbe (1902-1994), one of the great moral voices of that generation, in a historical address six months after the event, Purim 1970, saw it as something far more profound and existential than just lots of youngsters living out their natural animal passions *.A little introduction is necessary.DrunkAn intriguing and uncharacteristic statement in the Talmud (the primary body of Jewish law and literature) declares that "On Purim a person is obligated to become intoxicated until he does not know the difference between 'Cursed is Haman' and 'Blessed is Mordechai.'" (Talmud, Megilah 7b).

In Judaism, excessive drinking is seen as both repulsive and destructive. In Genesis we are informed that intoxication by Noah and then Lot led to disaster. Little needs to be said today to validate this truth. In America today, as in so many other parts of the world, alcoholism has destroyed too many a life and family. For people who have fallen prey to the devil of addiction, no religious excuse should ever be employed to allow the horrible demon of alcoholic or drug addiction to destroy themselves and their loved ones.

Yet for individuals living up to Talmudic moral and spiritual standards - abstaining from any form of excessive drinking all year around and, instead, toiling to refine their characters and dispositions under complete sobriety -- Jewish tradition designates one day of the year when they ought to leave the inhibitions of the rational mind in order to express the depth and glow of their passions, which are usually stored in the super-conscious chambers of their souls. An individual who has dedicated an entire year to work soberly on his or her psychological, emotional and spiritual identity, as Judaism incessantly demands, is highly unlikely to be pulled down by the once-a-year consumption of alcohol.

Still, the Talmud's demand that under the spell of intoxication one ought to forget the difference between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" seems absolutely bizarre.

Haman was a ruthless power monger, a self-centered egomaniac and an evil barbarian who schemed to exterminate every single Jew living in the Persian Empire. He was the Hitler of his day. Mordechai, on the other hand, was a saintly sage, a genuine leader, a lover of G-d, of his people and of humanity. It seems obvious that a decent human being should never forget that Haman must be cursed and Mordechai blessed. Moral equations between monsters and good people, although popular in some academic circles today, are grotesque and disgusting. They allow the monsters to continue their work.

What is even more bizarre is that we are enjoined to engage in this forgetfulness on the Jewish holiday of Purim - the day in which we celebrate Jewish deliverance from the vicious Haman as a result of the courageous spiritual and political leadership of Mordechai. The very holiday of Purim is about the fall of Haman and the rise of Mordechai. How, then, are we to make sense of the Talmud's demand that on Purim we know not "the difference between 'Cursed is Haman' and 'Blessed is Mordechai' when this distinction is what constitutes the very essence and purpose of the holiday!

Obviously, then, we must understand these words of the Talmud in a deeper way. Indeed, interpretations are abundant. What follows is one of my personal favorites presented by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, delivered at that Purim assembly in 1970, some six months after Woodstock.

Why Should I Be a Good Person?

There are two levels of consciousness, the Rebbe explained, in which one can distinguish between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai." The first is pragmatic and materialistic; the second is soulful and eternal. One speaks in the name of self-interest and personal gain, the other in the name of meaning.

From a pragmatic and materialistic world outlook, Haman's path ought to be rejected, and Mordechai's lifestyle embraced. Indeed, many of our parents and grandparents employed the pragmatic argument in order to persuade us to live the good and decent life.

"If you wish to get into a good college," they told us, "you should keep away from drugs and alcohol. If you want to graduate with honors, you must abstain from promiscuity and frivolousness. If you desire to be hired by a successful firm or company, you need to demonstrate responsibility, consistency and trust and get a good education. If you want to generate a good income, live in a beautiful home, take a few vacations a year, and own three cars and a summer home, you need to get up early each morning, put in a full day at the office, remain loyal to your spouse and stay away from dangerous and trippy behavior. If you wish to be respected socially and invited to upper-class receptions, stay away from any form of racism, bigotry and violence. You must behave like a 'mentch.'

"And," they continued, "if you manage to give some charity on the side, you might even be honored one day at fund-raising dinners and have your name engraved on a building or two. When you hit old age, you will retire with dignity, accompanied by a hefty savings account and time for golf and relaxation. If you make enough money, you may even establish a tax-deductible foundation on your name."

This is, admittedly, a nice vision (a certain part of me likes it too, though I must confess I have at this stage of my life already violated many of the ground rules.) It promotes decent behavior, loyal citizenship, hard work and faithful family commitments. It works for many youngsters and has proven successful with many American Jews who made a life for themselves. Yet it proved futile with millions of American and Jewish youngsters who in the 1960s revolted against the "Establishment" and embraced a lifestyle of boundless frivolousness, uninhibited intimacy and uncontrolled acid trips.

In the view of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, large segments of American youth were consciously or subconsciously rejecting the pragmatic but essentially self-serving philosophy of their teachers and parents because it failed to address the depth of their souls. It spoke in the name of financial security, comfortable living and a respectable social status. It attempted to impress them with the glamour of a comfortable life style, a nice home, beautiful clothes and engaging entertainment.

These are certainly tempting to many of us. But what about the idealistic cords inherent in the soul of our youth? What about the passion for truth and the dedication emblematic of the human spirit? What about human beings' quest to touch infinity and live a life of true meaning? On this count the Establishment failed them miserably then, as it does so often now. Not because it demanded too much, but because it expected too little. It reduced souls to machines, spirits to robots and humans capable of moral greatness to self-centered creatures. It spoke not to the profoundest passions of our youngsters but rather to their most superficial instincts. It addressed not their idealistic and spiritual yearnings, only their bodies and physical cravings.“We are not only animals,” was the subconscious cry of a generation, “searching for self gratification and self aggrandizement. We are souls; we care not only about a capitalistic secure financial future, but for deep meaning and the echo of truth.”

When the distinction between "Cursed is Haman" and "Blessed is Mordechai" is founded merely on materialistic, self-serving and pragmatic benefits rather than on the deepest passions and commitments of the human soul; when it speaks in the name of external satisfaction rather than with the voice of existential wholesomeness, the youthful spirit is likely to reject it and, in his or her rebelliousness, travel to the opposite extreme where the distinctions between Haman and Mordechai are blurred and all moral standards become hazy and meaningless.When the goals of education and decent behavior are motivated by superficial human qualities they do not resonate with deeper, more sensitive and more spiritual kids. And in their attempt to touch their own depth, they reject all standards and boundaries.Shattering the Myth

This is the meaning behind the Talmud's demand that on Purim we must lose our knowledge of the distinction between Haman's evil and Mordechai's goodness. There is no question that even on Purim we must know the difference between good and evil, between light and darkness, between love and hate, between a life committed to building the world and a life dedicated to destroying it. Never are we permitted to forget the difference between a lifestyle of morality and virtue vs. a lifestyle of immorality and selfishness.

What the Talmud is telling us, however, is that for the distinction between the two to resonate deeply and eternally, sometimes the superficial basis for the distinction between the two paths of life must first be destroyed. It is only after we know not the difference between Haman and Mordechai on a superficial level – because we are not driven merely by our selfish instincts and motivations -- that we can discover the essential difference on a far truer and deeper level.And this, the Rebbe concluded, was the true calling behind the rebelliousness of the youth. They were rejecting the superficial distinctions between “Haman” and “Mordechai,” because these did not resonate with their deep, sensitive souls. Morality must speak in the name of truth and depth, not in the name of shallow narcissistic benefits. “Don’t blame the youth, blame the educators,” the Rebbe declared.Now, he believed, we have the opportunity to teach the youth about the true and profound distinctions between the two lifestyles and philosophies, founded on the soul's awareness that man was created to become larger than human, and that in a life committed to goodness, kindness, morality and the service of G-d the soul encounters itself in its profoundest dreams, tragedies and hopes.

And Today...

Forty years have passed. Woodstock today is nostalgia. And even nostalgia today is not what it used to be like, as one old nostalgic man remarked.Yet so many youth still find themselves in the muddy fields of unrestrained passion and behavior. Are they too not responding to the superficial messages coming from their teaches and parents?*) The Lubavitcher Rebbe, in his usual style of avoiding direct references, did not mention Woodstock by name, only an entire generation of young people who rejected the Establishment.- Comment

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein

In honor of their new-born nephew Menachem Mendel Schottenstein

Class Summary:

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!