The Mule and the Salt

- October 3, 2012

- |

- 17 Tishrei 5773

Rabbi YY Jacobson

43 views

Abraham Foxman meets Rabbi Leo Goldman

The Mule and the Salt

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2012

In the Maternity Ward

It is a surreal scene. No eye remains dry when Yaakov Kroyzer, a Vishnitzer Chassid living in Jerusalem, takes his tallis and covers around 100 infants, newly born babies, in a hospital in the Kiryat Yearim neighborhood in Jerusalem.

On Simchat Torah it is customary that even children receive an aliya to the Torah. In synagogues the world over, all the children are gathered together under a tallis and, together with the adult who received this honor, recite the traditional aliya blessings. So Yaakov Kroyzer decided to take it a step further: He makes a Simchas Torah minyan in the maternity ward in the hospital near his home with all of the new infants under the tallis, as all of them get called up to the Torah each year on Simchat Torah!

Mr. Kroyzer has a tallis 30 feet long, with which he bedecks all of the infants. “I am doing it for more than 20 years,” he related recently in a web interview, “and never did any child cry while under the tallis.”

Before they receive the aliya, he gives his annual victory speech which lasts for 20 seconds: “70 years ago, they murdered one and a half million infants and children. Today, 100 of our children, together with hundreds of thousands of children the world over, are being called up to the Torah. This is our victory.” He then calls up all of the children to their aliya, they read the Torah, and a choir sings the songs “hamalach hagoel,” and “vezakeni legadel banim,” blessing these children with a most beautiful and blessed life. [You may ask your cantor to sing]. Not a single mother and father in the audience retains a dry eye.[1]

But why? Why do we call up our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah, something we do not do all year around?[2]

The Grand Debate

For this, we have to explore a fantastical and enigmatic story in the Talmud.

[Note: We discussed this debate in the sermon of Shabbos Haazenu 5773. If you did it, you can skip straight to the actual debate.]

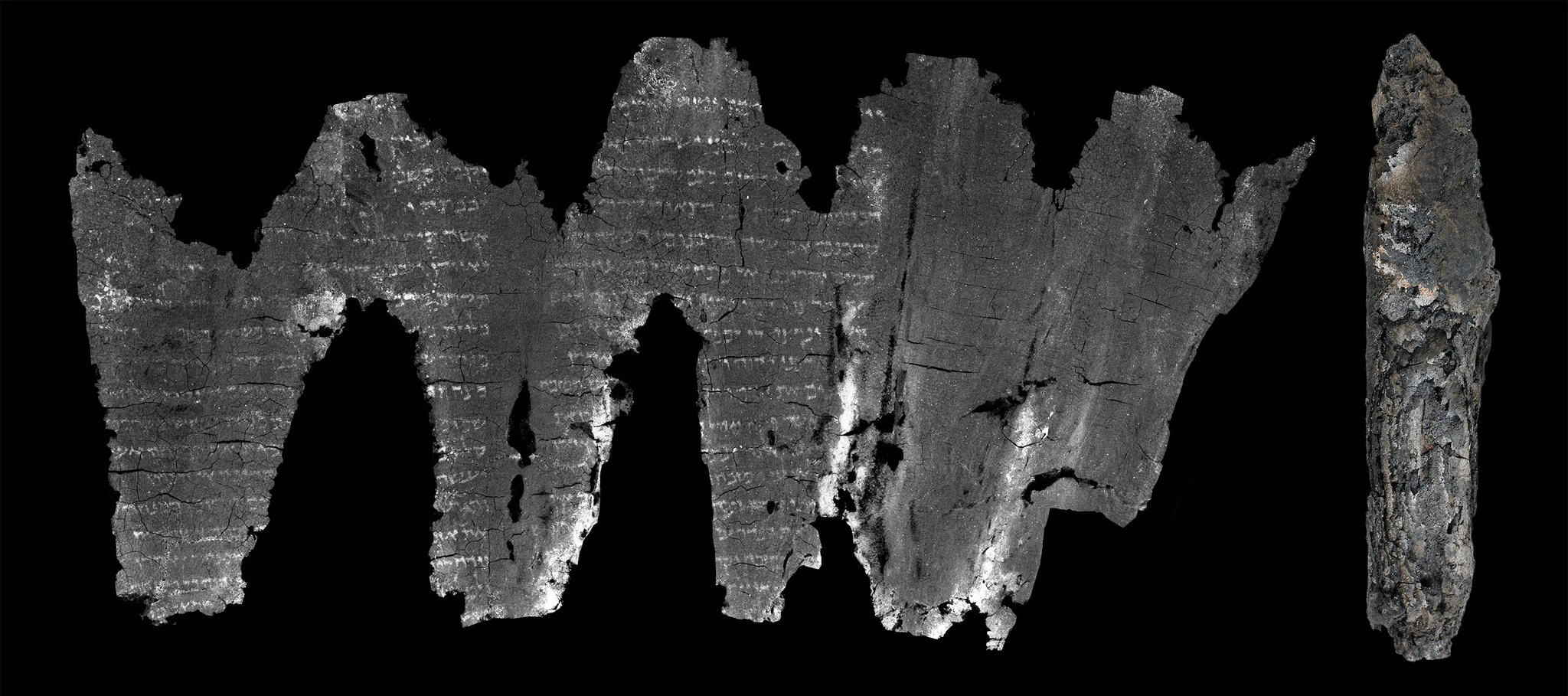

Some 1900 years ago, during the first century CE, only a few years after the destruction of the second Temple by the Romans in the year 70 CE, a great debate took place between the Jews and the Greeks.

The Talmud[3] recounts the fascinating confrontation that occurred between the Wise Men of Athens and the great sage of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya. Athens was known in the ancient world as the seat of wisdom and philosophy, and its sages saw themselves as the deepest and wisest thinkers of the time. Amongst the sages of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua stood out as the sharpest and most quick-witted, a fearsome debater and a brilliant scholar, though to earn a livelihood he would sell charcoal.[4]

He was a Levite who played music back in the Second Temple[5] (the Levites would perform a daily morning concerto in the Temple) and witnessed its destruction. In the following decades, one of the worst periods in all of our history, Rabbi Yehoshua served as the most prominent spokesman for Judaism and the Jewish people. [6]

So when the Roman Caesar demanded to test who was wiser—the Jews or the Greeks—Rabbi Yehoshua was the clear choice to represent the Torah of Israel.

A Conflict of Riddles

Sixty sages of Athens challenged the singular Jewish sage and the battle of wits began. The Talmud records the back and forth between these sages, that took the form of a cryptic exchange of riddles. The Athenian scholars would throw a challenge in front of Rabbi Yehoshua, and Rabbi Yehoshua would come back with an answer each time, usually in the form of a counter-question. Part of the exchange went like this.

בכורות ח, ב: ורצוצא דמית מהיכא נפיק רוחיה? מהיכא דעל נפק

The sages of Athens asked: "If a chick dies while in the egg, before the egg is hatched [and it is sealed from all sides], from where does its soul escape?" Rabbi Yehoshua's response: "The soul escapes through the same place it entered [into the sealed egg]."

משרא דסכיני במאי קטלי בקרנא דחמרא ומי איכא קרנא לחמרא ומי איכא משרא דסכיני

They further asked, "How do you harvest a field of knives?” Rabbi Yehoshua answered: "You use a donkey's horn." The elders: "But donkeys do not have horns!" Rabbi Yehoshua: "And knives do not grow in a field!"

Each one of these exchanges—and there were many of them—begs explanation. What do these bizarre questions really mean, and what lies behind the sharp answers? What wisdom is being displayed here?

The various Talmudic commentaries all agree that the conversations between the Rabbi and the Greeks were allegorical. They were discussing lofty issues of the spirit, the meaning of life and death, G-d's role in the universe, human destiny, the meaning of existence, the concept of the “chosen people,” the cardinal principles of Judaism. They spoke in symbolic terms, the language of wise men, and their words are not to be taken literally.

Salting Salt

But today I want to discuss the one of their other absurd exchanges.

מילחא כי סריא, במאי מלחי לה? אמר להו בסילתא דכודניתא. ומי איכא סילתא לכודנתא? ומילחא מי סרי.

[תרגום ללשון הקודש: (אמרו לו) מלח שמסריח, במה מולחים אותו (כדי לשומרו)? אמר להם, בשליה של פרדה. אמרו לו, וכי יש שליה לפרדה? אמר להם: וכי מלח מסריח?]

They asked him, "When salt gets spoiled, what do we use to preserve it?" His response: "We use the afterbirth of a mule." (This is the embryonic sac which shelters and preserves the developing fetus.) "Do mules have afterbirth?" they asked. [A mule cannot give birth.] "Does salt spoil?" he retorted.

Is this an intelligent conversation between the representatives of the house of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the representative of the Torah of Israel? What are they asking and what is Rabbi Yehoshua answering?

In truth, this absurd exchange symbolized a profound debate—one that endured for thousands of years and rages to this very day. It confronts the important question: What is the relevance of Torah and Judaism in the modern world?[7]

Time To Update the Religion

When the Elders of Athens spoke about salt, they were referring to Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People. They considered that this preservative had spoiled; that it had become rancid, obsolete and irrelevant.

A student once prepared a thesis. The professor wrote on the manuscript that it is both good and original, but then proceeded to fail the student. When the student wondered why he failed, the teacher replied: "The manuscript is both good and original, but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good."

Judaism, the Greeks maintain, is old, very old; the Torah is not an original work written in this century and it needed a tune-up. After all, those were the glorious days of Greek culture, and even many Jews were seeing the Torah as being old-fashioned. Rather than observe Shabbos, they wanted to join the Greek Gymnasiums. Rather than study Torah, they wanted to study Greek philosophy. Rather than sit in a Sukkah, shake a lulav or put on tefilin and daven, they gravitated to Zeus and Olympus, to Homer, Socrates and Plato.

It was time, said the Elders of Athens, to salt the salt. The salt was not old and sour. It was time to change the Torah in order to keep it in the spirit of the day and ensure its popularity. It was time to make some reforms to Judaism. Judaism was ready for an upgrade, for iPhone 5, it needed some cosmetic and substance changes, to make it more fresh, exciting and relevant to a new age inspired by Greek esthetics, philosophy, culture, athleticism, art, drama and literature. Mikvah, tefilin, kosher, Torah study, Torah education, Shabbos candles, Mezuzah, a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashanah, crunchy matzah, the laws of modesty, and the 613 Mitzvos of Torah desperately need a make over. In one word, the salt needs to be salted.

The Mule

Rabbi Yehoshua replied that they should use the afterbirth of a mule. It was a brilliant reply astonishing in its vision, truth and in the method he conveyed such a profound truth. What is a mule? The hybrid offspring of a female horse and a male donkey. At first sight, a mule seems like an awesome animal; it is strong, sure-footed, resistant to disease, and long-lived. By taking elements of the donkey and of the horse, we seem to have the best of both worlds. It has been claimed that mules are "more patient, sure-footed, hardy and long-lived than horses, and they are considered less obstinate, faster, and more intelligent than donkeys."[8] What an awesome combination. It’s just like a Hellenized, modernized Judaism – hybridizing the two cultures in order to have the best of both worlds.

There’s just one problem. Mules can’t breed. They are sterile.

Rabbi Yehoshua was saying: If you try to alter Judaism, to “update” it and combine it with the latest fads, it will look great, and it will doubtless be very popular, the new show in town. But it won’t last. It’s not authentic and it can’t perpetuate. When the sages of Athens explained to him that mule is sterile, Rabbi Yehousha responded, that salt cannot go rancid. Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People, will continue to preserve them, as long as it is left pure and unadulterated.

Torah is salt and salt does not get rancid. It will endure forever, because it is rooted in the source of all life and history, in the Divine. Torah is always relevant because its truths span and pervade all of history, all cultures, all milieus, all circumstances. When we attempt to present a new Judaism, less ancient and more modern, it may be appealing short term. But it will prove sterile in the long term. It will not last. The grandchildren will be lost.

The Results

Was Rabbi Yehoshua right?

1900 years later, we know the answer. Samuel Clemens, popularly known as Mark Twain, famously wrote: "The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, and then passed away. The Greek and the Roman followed. The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?"

What is more, all movements within Judaism which have advocated (as a philosophy) that we alter the Torah and its mitzvos, in order to make it more palpable and appealing to the youth, have become sterile. They perhaps had good intentions, they wanted to preserve Judaism, but their preservatives have proven counter-productive: You don’t try to preserve salt with superficial preservatives. Salt itself is its own best preservative!

The secret of Judaism lay not in the fact that it addresses the fad of the day, that it accommodates the political sentiment of the hour; that it speaks of the new dress design or the latest TV series. The true power of Judaism lay in the fact that it addresses the transcendent needs, yearnings and passions of the human being, truths that transcend time and space, needs that are timeless, aspirations that are eternal.

Shabbas refreshed souls and sanctified homes 3,000 years ago, and it still does so today; tefilin synchronized minds and hearts to our mission in life 2000 years ago and it still does so today; mikvah gave intimacy its holiness and freshness 1000 years ago, it still does so today; Torah study gave moral vision and spiritual inspiration 500 years ago, it still does so today.

When I put on tefillin in the morning, I know that these very same tefillin were donned by Jews in Eretz Israel in 1200 BCE; by Jews in Babylonia in 500 BCE; by Jews in Iran in 100 CE; by Jews in Spain in 1000; by Jews in Poland and Austria in 1600; by my great-great-grandparents in Lithuania in 1850; by Jews in Auschwitz in 1943; and by millions of Jews from Sydney to Los Angeles in 2012.

If Moses and Aaron walk in today to [name the main business center district of your city], they will recognize almost nothing. If they enter our shul today, they will be familiar with so much: the same mezuzah, the same tefillin, the same talit, the same Torah scroll, the same Sukkah, the same shofar, the same lulav and esrog; 3,324 years, and the same Torah that Moses taught his children, we are teaching our children. [9]

The Story of Henryk-Abraham[10]

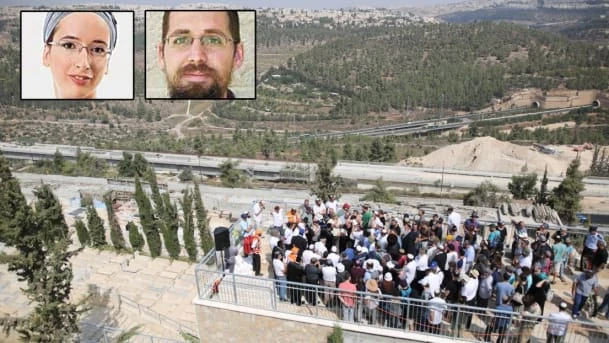

Henryk was very young in 1945, when the War ended and solitary survivors tried frantically to trace their relatives. He had spent what seemed to be most of his life with his nanny, who had hidden him away from the Nazis at his father's request. There was great personal risk involved, but the woman had readily taken it, as she loved the boy.

All the Jews were being killed, and Henryk's nanny did not think for a moment that the father, Joseph Foxman, would survive the infamous destruction of the Vilna Ghetto. He would surely have been transferred to Auschwitz — and everyone knew that nobody ever came back from Auschwitz. She therefore had no scruples about adopting the boy, having him baptized into the Catholic Church and taught catechism by the local priest.

The nanny saved his life—but also taught him to spit on the ground when a Jew walked by.

It was Simchat Torah when his father came to take him. The heartbroken nanny had packed all his clothing and his small catechism book, stressing to the father that the boy had become a good Catholic. Joseph Foxman took his son by the hand and led him directly to the Great Synagogue of Vilna. On the way, he told his son that he was a Jew and that his name was Avraham.

Not far from the house, they passed the church and the boy reverently crossed himself, causing his father great anguish. Just then, a priest emerged who knew the boy, and when Henryk rushed over to kiss his hand, the priest spoke to him, reminding him of his Catholic faith.

Everything inside of Joseph wanted to drag his son away from the priest and from the church. But he knew that this was not the way to do things. He nodded to the priest, holding his son more closely. After all, these people had harbored his child and saved the child's life. He had to show his son Judaism, living Judaism.

They entered the Great Synagogue of Vilna, now a remnant of a past, vibrant Jewish era. There they found some Jewish survivors from Auschwitz who had made their way back to Vilna and were now rebuilding their lives and their Jewish spirits. Amid the stark reality of their suffering and terrible loss, in much diminished numbers, they were singing and dancing with real joy while celebrating Simchat Torah.

Only 3,000 of Vilna's 100,000 Jews remained.

Avraham stared wide-eyed around him and picked up a tattered prayer book with a touch of affection. Something deep inside of him responded to the atmosphere, and he was happy to be there with the father he barely knew. He held back, though, from joining the dancing.

A Jewish man wearing a Soviet Army uniform could not take his eyes off the boy, and he came over to Joseph. "Is this child... Jewish?" he asked, a touch of awe in his voice.

The father answered that the boy was Jewish and introduced his son. As the soldier stared at Henryk-Avraham, he fought to hold back tears. "Over these four terrible years, I have traveled thousands of miles, and this is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all this time. I did not see a single Jewish child. They were all murdered. This is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all these years... Would you like to dance with me on my shoulders?" he asked the boy, who was staring back at him, fascinated.

The father nodded permission, and the soldier hoisted the boy high onto his shoulders. With tears now coursing down his cheeks and a heart full of real joy, the soldier joined in the dancing.

"This is my Torah scroll," he cried, as he danced with the five year old Jewish boy.

The Abraham in our story you all heard of: His name is Abe Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League.

The Reunion

But this is not the end of the story.

For 65 years, the boy and the soldier carried that moment in their heads and hearts. Unknown to each other, they told the story to family and friends.

But then something happened. The Jewish composer Abie Rotenberg put together a song, "The Man From Vilna," about the incident with a Michigan rabbi dancing with a Jewish boy. Foxman heard the song and he learned that the Jewish Soviet soldier was a man named Goldman, still alive and living in the United States.

Two years ago, they met and embraced for the first time since 1945. As it turns out, the Soviet soldier is 93 year old Rabbi Leo Goldman from Oak Park, Detroit, an Orthodox rabbi and an educator

The two men hugged and talked and recited the blessing of “Shecheyanu vekeymanu veheganu lizman hazeh.”[11]

Dance With Your Children

That is why we call up all of our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah—because this is what captures the reason for our never ending celebration of the Torah: In a world where every fad turns into a mule, we celebrate the “salt” which never grows old, sour or rancid. It is our children that demonstrate to us the eternal value of Torah.

Friends, we are not in Vilna in 1945. We are, thank G-d, living in freedom. Abe Foxman’s life was changed because of that single dance. We ought not to deprive our children of that dance.

Let us bring our children, grandchildren and friends for our Simchat Torah celebration. And let us dance away with them. Life up your children—or your friend’s children—or your grandchildren on your shoulders and dance with them. Dance and dance. Let us dance with millions of Jews who will all dance with us on this Simchas Torah celebrating the Divine gift of Torah which becomes more fresh, more relevant, and more exciting each year.

Let us dance away and commit ourselves this coming year to embrace the Torah in our lives, by increasing in our study of Torah. Join a Torah class. Study Torah on your own. But don’t let the ultimate preservative of history slip through your fingers.

[As we are about to say yizkor, we remember what our loved ones have given us, the “salt” that passed on to us, and we commit to share that eternal “salt” with our children.]

[1] For the full story and photos, see: http://www.bhol.co.il/article_old.aspx?id=33026

[2] The Malbushei Yom Tov gives this reason:

שגם הם ידעו, שיש להם אות וחלק בתורה ולחנכם במצוות ולשתפם בשמחת התורה. מצאתי על קלף, ש"בחיי" (רבנו "בחיי", מחבר הפירוש תורה) כתב למחות [נגד המנהג] לזרוק פירות לנערים בשמחת תורה; אבל יש במדרש, שזה היה אומר המן למלך (אחשורוש) על היהודים. אם כן מנהג קדמון הוא. ואולי (מחה רבינו בחיי על מנהג זה כיון) שראה ה"בחיי" בימיו, שנוהגים בזה ריקות והוללות. (מלבושי יום טוב).

[3] Bechoros 8b

[4] Talmud Berachos 28a

[5] Talmud Erkin 11

[6] See Talmud Chagigah 5b

[7] The following explanation is based on Maharsha to Bechoros 8b and Sefer Dorash Moshe derush 32. Cf. Chidushei Agados Maharal, Perus HaGra, and Likkutei Mahran for alternative explanations to this exhchange.

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mule footnote 3

[9] You can share these two stories:

I want to share with you a story that I heard from the former chief rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Israel Meir Lau. In 1989, when Gorbachev first introduced Glasnost to the Soviet Union, as a gesture to the Jewish community he invited an international delegation of rabbis to visit Moscow. They were to spend six days with the Jewish community. Rabbi Lau was one of the rabbis selected. They spoke in various synagogues, gave encouragement and inspired many with hope for tomorrow. On their last night in the Moscow shul, an old man named Berel asked Rabbi Lau if he could escort him to his hotel. Rabbi Lau agreed. The shul was about a half hour walk from the hotel.

Reb Berel began to cry. "You come here, you teach, you sing with us, you have Shabbos with us, you lift us up so high, and then you leave us. You go home and we're here alone, back in the pit of despair again. (Remember, that in those days shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, there was absolutely no infrastructure of Jewish life in the country.)

Rabbi Lau said, "Reb Berel, how old are you?"

"I'm 86 years old."

"What do you do for a living?"

"I'm a butcher, but I have not seen a piece of meat in years."

"Reb Berel, the Russians won't care if you leave. I made some connections here. Let me work on it tonight and tomorrow you will join me on the flight back to Eretz Yisroel, to Israel. You'll be out of the pit for good."

The old man lets out a loud krecthz, a sigh. "Oh to see Yerushalayim; to touch the Western Wall; to breathe the air of our homeland. It is a dream come true. What I wouldn't do to kiss the land of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob."

And then Berel stopped short, and continued: "How much can a person think only of himself? I have one daughter and she married out, a Russian gentile. They don't live near Moscow. She has two children. Two young Jewish boys. One is nine years old and the other one is seven years old. They are my grandchildren, my ainiklach. Once a month my daughter brings my grandchildren to visit their zaide. That day is so dear to me. I get dressed up in my Shabbat clothes and I place one grandson on one knee, the second grandson on the other knee, and I say with them Shema Yisroel Hashem elokainu Hashem echod. I say with them Torah tziva lanu Moshe. I teach them about Moshe Rabbeinu. I teach them about Shabbos, about Rosh Hashanah, about Pesach. I teach them who they are. I sing with them the melodies I heard from my mother and grandmother; I share with them our story, a story that began thousands of years ago and is still going strong.

"Those two hours a month are the only two hours of Judaism they get and those two hours are the most precious two hours of my entire month. If I leave with you to Israel, who will tell them that they are Jewish? Who will see to it that the chain continues? Who will teach them to be proud to be a Jew?"

Somewhere in the world today, there are two brothers, one 32 and one 30, and they know about their heritage. They know that they are "messengers," that they are part of a chain, because their zaide was willing to sacrifice for them.

A second story:

In April 1943, in the Warsaw ghetto, a Jewish family was conducting a seder in a bunker. It was the first night of Passover when the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising broke out.A child in the family asked the four questions. And then he continued, “Tatti, can I ask you a fifth question"?

The father said, for sure.

So the boy continued with his fifth question: "Why is our nation different than all other nations? Why have we been targeted for abuse and annihilation?"

His father answered, “The Jewish nation began before any other nation had, and it will survive long after the Third Reich is dead. One cannot understand a story if one does not first know the entire story, from beginning to end, and our story is not over yet…"

"Tatty, I have a sixth question. Next year will I be here to ask you these four questions? Will you be here to answer them?"

And the father said, “I’ll be honest with you, my son. I hope yes, but I am not sure. Yet this I want you to know: There is an expression in the sedur, “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished." So I can promise you that somewhere in the world there will be a Moshele or a Dovidl, a saraleh or a racheleh, asking these four questions to their father and mother."

My dear friends, that little boy and his father perished. But last Passover, at the seder table, 3 million Jewish children turned to their mother's and father's and said, "Tatti, Mammi, I want to ask you four questions…"

My friends, this is why we are all here today. “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished."

- Comment

Class Summary:

It is a surreal scene. No eye remains dry when Yaakov Kroyzer, a Vishnitzer Chassid living in Jerusalem, takes his tallis and covers around 100 infants, newly born babies, in a hospital in the Kiryat Yearim neighborhood in Jerusalem, giving them all an aliya for Simchas Torah. Before the aliya, he gives a 20-second speech: 70 years ago, infants like yourself were sent to the gas chmabers. Today, you are under a tallis being called up to the Torah, celebrating our heritage, and perpetuating our eternal values and hopes.

Why do we call up our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah, something we do not do all year around?

For this, we have to explore a fantastical and enigmatic story in the Talmud, recording a debate 1900 years ago between the sages of Athens, the great wise men of Greece, and the Jewish sage Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya. They asked him, "When salt gets spoiled, what do we use to preserve it?" His response: "We use the afterbirth of a mule." (This is the embryonic sac which shelters and preserves the developing fetus.) "Do mules have afterbirth?" they asked. [A mule cannot give birth.] "Does salt spoil?" he retorted. And he won the debate.

Is this an intelligent conversation between the representatives of the house of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the representative of the Torah of Israel? What are they asking and what is Rabbi Yehoshua answering?

In truth, this absurd exchange symbolized a profound debate—one that endured for thousands of years and rages to this very day. It confronts the important question: What is the relevance of Torah and Judaism in the modern world?

It was Simchat Torah when his father came to take him—his little boy who was raised by the Catholics throughout the Holocaust. The heartbroken Christian nanny had packed all his clothing and his small catechism book, stressing to the father that the boy had become a good Catholic. Joseph Foxman took his son by the hand and led him directly to the Great Synagogue of Vilna. On the way, he told his son that he was a Jew and that his name was Avraham. In the shul, it was a Soviet soldier who lifted him up on his shoulders, dancing with him, crying: This is my Sefer Torah!

And in 2010, the two met again—the soldier and the boy. One turned out to be the head of ADL and the other a prominent Rabbi in Detroit. They both made a resounding Shecheyanu.

In the Maternity Ward

It is a surreal scene. No eye remains dry when Yaakov Kroyzer, a Vishnitzer Chassid living in Jerusalem, takes his tallis and covers around 100 infants, newly born babies, in a hospital in the Kiryat Yearim neighborhood in Jerusalem.

On Simchat Torah it is customary that even children receive an aliya to the Torah. In synagogues the world over, all the children are gathered together under a tallis and, together with the adult who received this honor, recite the traditional aliya blessings. So Yaakov Kroyzer decided to take it a step further: He makes a Simchas Torah minyan in the maternity ward in the hospital near his home with all of the new infants under the tallis, as all of them get called up to the Torah each year on Simchat Torah!

Mr. Kroyzer has a tallis 30 feet long, with which he bedecks all of the infants. “I am doing it for more than 20 years,” he related recently in a web interview, “and never did any child cry while under the tallis.”

Before they receive the aliya, he gives his annual victory speech which lasts for 20 seconds: “70 years ago, they murdered one and a half million infants and children. Today, 100 of our children, together with hundreds of thousands of children the world over, are being called up to the Torah. This is our victory.” He then calls up all of the children to their aliya, they read the Torah, and a choir sings the songs “hamalach hagoel,” and “vezakeni legadel banim,” blessing these children with a most beautiful and blessed life. [You may ask your cantor to sing]. Not a single mother and father in the audience retains a dry eye.[1]

But why? Why do we call up our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah, something we do not do all year around?[2]

The Grand Debate

For this, we have to explore a fantastical and enigmatic story in the Talmud.

[Note: We discussed this debate in the sermon of Shabbos Haazenu 5773. If you did it, you can skip straight to the actual debate.]

Some 1900 years ago, during the first century CE, only a few years after the destruction of the second Temple by the Romans in the year 70 CE, a great debate took place between the Jews and the Greeks.

The Talmud[3] recounts the fascinating confrontation that occurred between the Wise Men of Athens and the great sage of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya. Athens was known in the ancient world as the seat of wisdom and philosophy, and its sages saw themselves as the deepest and wisest thinkers of the time. Amongst the sages of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua stood out as the sharpest and most quick-witted, a fearsome debater and a brilliant scholar, though to earn a livelihood he would sell charcoal.[4]

He was a Levite who played music back in the Second Temple[5] (the Levites would perform a daily morning concerto in the Temple) and witnessed its destruction. In the following decades, one of the worst periods in all of our history, Rabbi Yehoshua served as the most prominent spokesman for Judaism and the Jewish people. [6]

So when the Roman Caesar demanded to test who was wiser—the Jews or the Greeks—Rabbi Yehoshua was the clear choice to represent the Torah of Israel.

A Conflict of Riddles

Sixty sages of Athens challenged the singular Jewish sage and the battle of wits began. The Talmud records the back and forth between these sages, that took the form of a cryptic exchange of riddles. The Athenian scholars would throw a challenge in front of Rabbi Yehoshua, and Rabbi Yehoshua would come back with an answer each time, usually in the form of a counter-question. Part of the exchange went like this.

בכורות ח, ב: ורצוצא דמית מהיכא נפיק רוחיה? מהיכא דעל נפק

The sages of Athens asked: "If a chick dies while in the egg, before the egg is hatched [and it is sealed from all sides], from where does its soul escape?" Rabbi Yehoshua's response: "The soul escapes through the same place it entered [into the sealed egg]."

משרא דסכיני במאי קטלי בקרנא דחמרא ומי איכא קרנא לחמרא ומי איכא משרא דסכיני

They further asked, "How do you harvest a field of knives?” Rabbi Yehoshua answered: "You use a donkey's horn." The elders: "But donkeys do not have horns!" Rabbi Yehoshua: "And knives do not grow in a field!"

Each one of these exchanges—and there were many of them—begs explanation. What do these bizarre questions really mean, and what lies behind the sharp answers? What wisdom is being displayed here?

The various Talmudic commentaries all agree that the conversations between the Rabbi and the Greeks were allegorical. They were discussing lofty issues of the spirit, the meaning of life and death, G-d's role in the universe, human destiny, the meaning of existence, the concept of the “chosen people,” the cardinal principles of Judaism. They spoke in symbolic terms, the language of wise men, and their words are not to be taken literally.

Salting Salt

But today I want to discuss the one of their other absurd exchanges.

מילחא כי סריא, במאי מלחי לה? אמר להו בסילתא דכודניתא. ומי איכא סילתא לכודנתא? ומילחא מי סרי.

[תרגום ללשון הקודש: (אמרו לו) מלח שמסריח, במה מולחים אותו (כדי לשומרו)? אמר להם, בשליה של פרדה. אמרו לו, וכי יש שליה לפרדה? אמר להם: וכי מלח מסריח?]

They asked him, "When salt gets spoiled, what do we use to preserve it?" His response: "We use the afterbirth of a mule." (This is the embryonic sac which shelters and preserves the developing fetus.) "Do mules have afterbirth?" they asked. [A mule cannot give birth.] "Does salt spoil?" he retorted.

Is this an intelligent conversation between the representatives of the house of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the representative of the Torah of Israel? What are they asking and what is Rabbi Yehoshua answering?

In truth, this absurd exchange symbolized a profound debate—one that endured for thousands of years and rages to this very day. It confronts the important question: What is the relevance of Torah and Judaism in the modern world?[7]

Time To Update the Religion

When the Elders of Athens spoke about salt, they were referring to Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People. They considered that this preservative had spoiled; that it had become rancid, obsolete and irrelevant.

A student once prepared a thesis. The professor wrote on the manuscript that it is both good and original, but then proceeded to fail the student. When the student wondered why he failed, the teacher replied: "The manuscript is both good and original, but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good."

Judaism, the Greeks maintain, is old, very old; the Torah is not an original work written in this century and it needed a tune-up. After all, those were the glorious days of Greek culture, and even many Jews were seeing the Torah as being old-fashioned. Rather than observe Shabbos, they wanted to join the Greek Gymnasiums. Rather than study Torah, they wanted to study Greek philosophy. Rather than sit in a Sukkah, shake a lulav or put on tefilin and daven, they gravitated to Zeus and Olympus, to Homer, Socrates and Plato.

It was time, said the Elders of Athens, to salt the salt. The salt was not old and sour. It was time to change the Torah in order to keep it in the spirit of the day and ensure its popularity. It was time to make some reforms to Judaism. Judaism was ready for an upgrade, for iPhone 5, it needed some cosmetic and substance changes, to make it more fresh, exciting and relevant to a new age inspired by Greek esthetics, philosophy, culture, athleticism, art, drama and literature. Mikvah, tefilin, kosher, Torah study, Torah education, Shabbos candles, Mezuzah, a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashanah, crunchy matzah, the laws of modesty, and the 613 Mitzvos of Torah desperately need a make over. In one word, the salt needs to be salted.

The Mule

Rabbi Yehoshua replied that they should use the afterbirth of a mule. It was a brilliant reply astonishing in its vision, truth and in the method he conveyed such a profound truth. What is a mule? The hybrid offspring of a female horse and a male donkey. At first sight, a mule seems like an awesome animal; it is strong, sure-footed, resistant to disease, and long-lived. By taking elements of the donkey and of the horse, we seem to have the best of both worlds. It has been claimed that mules are "more patient, sure-footed, hardy and long-lived than horses, and they are considered less obstinate, faster, and more intelligent than donkeys."[8] What an awesome combination. It’s just like a Hellenized, modernized Judaism – hybridizing the two cultures in order to have the best of both worlds.

There’s just one problem. Mules can’t breed. They are sterile.

Rabbi Yehoshua was saying: If you try to alter Judaism, to “update” it and combine it with the latest fads, it will look great, and it will doubtless be very popular, the new show in town. But it won’t last. It’s not authentic and it can’t perpetuate. When the sages of Athens explained to him that mule is sterile, Rabbi Yehousha responded, that salt cannot go rancid. Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People, will continue to preserve them, as long as it is left pure and unadulterated.

Torah is salt and salt does not get rancid. It will endure forever, because it is rooted in the source of all life and history, in the Divine. Torah is always relevant because its truths span and pervade all of history, all cultures, all milieus, all circumstances. When we attempt to present a new Judaism, less ancient and more modern, it may be appealing short term. But it will prove sterile in the long term. It will not last. The grandchildren will be lost.

The Results

Was Rabbi Yehoshua right?

1900 years later, we know the answer. Samuel Clemens, popularly known as Mark Twain, famously wrote: "The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, and then passed away. The Greek and the Roman followed. The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?"

What is more, all movements within Judaism which have advocated (as a philosophy) that we alter the Torah and its mitzvos, in order to make it more palpable and appealing to the youth, have become sterile. They perhaps had good intentions, they wanted to preserve Judaism, but their preservatives have proven counter-productive: You don’t try to preserve salt with superficial preservatives. Salt itself is its own best preservative!

The secret of Judaism lay not in the fact that it addresses the fad of the day, that it accommodates the political sentiment of the hour; that it speaks of the new dress design or the latest TV series. The true power of Judaism lay in the fact that it addresses the transcendent needs, yearnings and passions of the human being, truths that transcend time and space, needs that are timeless, aspirations that are eternal.

Shabbas refreshed souls and sanctified homes 3,000 years ago, and it still does so today; tefilin synchronized minds and hearts to our mission in life 2000 years ago and it still does so today; mikvah gave intimacy its holiness and freshness 1000 years ago, it still does so today; Torah study gave moral vision and spiritual inspiration 500 years ago, it still does so today.

When I put on tefillin in the morning, I know that these very same tefillin were donned by Jews in Eretz Israel in 1200 BCE; by Jews in Babylonia in 500 BCE; by Jews in Iran in 100 CE; by Jews in Spain in 1000; by Jews in Poland and Austria in 1600; by my great-great-grandparents in Lithuania in 1850; by Jews in Auschwitz in 1943; and by millions of Jews from Sydney to Los Angeles in 2012.

If Moses and Aaron walk in today to [name the main business center district of your city], they will recognize almost nothing. If they enter our shul today, they will be familiar with so much: the same mezuzah, the same tefillin, the same talit, the same Torah scroll, the same Sukkah, the same shofar, the same lulav and esrog; 3,324 years, and the same Torah that Moses taught his children, we are teaching our children. [9]

The Story of Henryk-Abraham[10]

Henryk was very young in 1945, when the War ended and solitary survivors tried frantically to trace their relatives. He had spent what seemed to be most of his life with his nanny, who had hidden him away from the Nazis at his father's request. There was great personal risk involved, but the woman had readily taken it, as she loved the boy.

All the Jews were being killed, and Henryk's nanny did not think for a moment that the father, Joseph Foxman, would survive the infamous destruction of the Vilna Ghetto. He would surely have been transferred to Auschwitz — and everyone knew that nobody ever came back from Auschwitz. She therefore had no scruples about adopting the boy, having him baptized into the Catholic Church and taught catechism by the local priest.

The nanny saved his life—but also taught him to spit on the ground when a Jew walked by.

It was Simchat Torah when his father came to take him. The heartbroken nanny had packed all his clothing and his small catechism book, stressing to the father that the boy had become a good Catholic. Joseph Foxman took his son by the hand and led him directly to the Great Synagogue of Vilna. On the way, he told his son that he was a Jew and that his name was Avraham.

Not far from the house, they passed the church and the boy reverently crossed himself, causing his father great anguish. Just then, a priest emerged who knew the boy, and when Henryk rushed over to kiss his hand, the priest spoke to him, reminding him of his Catholic faith.

Everything inside of Joseph wanted to drag his son away from the priest and from the church. But he knew that this was not the way to do things. He nodded to the priest, holding his son more closely. After all, these people had harbored his child and saved the child's life. He had to show his son Judaism, living Judaism.

They entered the Great Synagogue of Vilna, now a remnant of a past, vibrant Jewish era. There they found some Jewish survivors from Auschwitz who had made their way back to Vilna and were now rebuilding their lives and their Jewish spirits. Amid the stark reality of their suffering and terrible loss, in much diminished numbers, they were singing and dancing with real joy while celebrating Simchat Torah.

Only 3,000 of Vilna's 100,000 Jews remained.

Avraham stared wide-eyed around him and picked up a tattered prayer book with a touch of affection. Something deep inside of him responded to the atmosphere, and he was happy to be there with the father he barely knew. He held back, though, from joining the dancing.

A Jewish man wearing a Soviet Army uniform could not take his eyes off the boy, and he came over to Joseph. "Is this child... Jewish?" he asked, a touch of awe in his voice.

The father answered that the boy was Jewish and introduced his son. As the soldier stared at Henryk-Avraham, he fought to hold back tears. "Over these four terrible years, I have traveled thousands of miles, and this is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all this time. I did not see a single Jewish child. They were all murdered. This is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all these years... Would you like to dance with me on my shoulders?" he asked the boy, who was staring back at him, fascinated.

The father nodded permission, and the soldier hoisted the boy high onto his shoulders. With tears now coursing down his cheeks and a heart full of real joy, the soldier joined in the dancing.

"This is my Torah scroll," he cried, as he danced with the five year old Jewish boy.

The Abraham in our story you all heard of: His name is Abe Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League.

The Reunion

But this is not the end of the story.

For 65 years, the boy and the soldier carried that moment in their heads and hearts. Unknown to each other, they told the story to family and friends.

But then something happened. The Jewish composer Abie Rotenberg put together a song, "The Man From Vilna," about the incident with a Michigan rabbi dancing with a Jewish boy. Foxman heard the song and he learned that the Jewish Soviet soldier was a man named Goldman, still alive and living in the United States.

Two years ago, they met and embraced for the first time since 1945. As it turns out, the Soviet soldier is 93 year old Rabbi Leo Goldman from Oak Park, Detroit, an Orthodox rabbi and an educator

The two men hugged and talked and recited the blessing of “Shecheyanu vekeymanu veheganu lizman hazeh.”[11]

Dance With Your Children

That is why we call up all of our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah—because this is what captures the reason for our never ending celebration of the Torah: In a world where every fad turns into a mule, we celebrate the “salt” which never grows old, sour or rancid. It is our children that demonstrate to us the eternal value of Torah.

Friends, we are not in Vilna in 1945. We are, thank G-d, living in freedom. Abe Foxman’s life was changed because of that single dance. We ought not to deprive our children of that dance.

Let us bring our children, grandchildren and friends for our Simchat Torah celebration. And let us dance away with them. Life up your children—or your friend’s children—or your grandchildren on your shoulders and dance with them. Dance and dance. Let us dance with millions of Jews who will all dance with us on this Simchas Torah celebrating the Divine gift of Torah which becomes more fresh, more relevant, and more exciting each year.

Let us dance away and commit ourselves this coming year to embrace the Torah in our lives, by increasing in our study of Torah. Join a Torah class. Study Torah on your own. But don’t let the ultimate preservative of history slip through your fingers.

[As we are about to say yizkor, we remember what our loved ones have given us, the “salt” that passed on to us, and we commit to share that eternal “salt” with our children.]

[1] For the full story and photos, see: http://www.bhol.co.il/article_old.aspx?id=33026

[2] The Malbushei Yom Tov gives this reason:

שגם הם ידעו, שיש להם אות וחלק בתורה ולחנכם במצוות ולשתפם בשמחת התורה. מצאתי על קלף, ש"בחיי" (רבנו "בחיי", מחבר הפירוש תורה) כתב למחות [נגד המנהג] לזרוק פירות לנערים בשמחת תורה; אבל יש במדרש, שזה היה אומר המן למלך (אחשורוש) על היהודים. אם כן מנהג קדמון הוא. ואולי (מחה רבינו בחיי על מנהג זה כיון) שראה ה"בחיי" בימיו, שנוהגים בזה ריקות והוללות. (מלבושי יום טוב).

[3] Bechoros 8b

[4] Talmud Berachos 28a

[5] Talmud Erkin 11

[6] See Talmud Chagigah 5b

[7] The following explanation is based on Maharsha to Bechoros 8b and Sefer Dorash Moshe derush 32. Cf. Chidushei Agados Maharal, Perus HaGra, and Likkutei Mahran for alternative explanations to this exhchange.

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mule footnote 3

[9] You can share these two stories:

I want to share with you a story that I heard from the former chief rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Israel Meir Lau. In 1989, when Gorbachev first introduced Glasnost to the Soviet Union, as a gesture to the Jewish community he invited an international delegation of rabbis to visit Moscow. They were to spend six days with the Jewish community. Rabbi Lau was one of the rabbis selected. They spoke in various synagogues, gave encouragement and inspired many with hope for tomorrow. On their last night in the Moscow shul, an old man named Berel asked Rabbi Lau if he could escort him to his hotel. Rabbi Lau agreed. The shul was about a half hour walk from the hotel.

Reb Berel began to cry. "You come here, you teach, you sing with us, you have Shabbos with us, you lift us up so high, and then you leave us. You go home and we're here alone, back in the pit of despair again. (Remember, that in those days shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, there was absolutely no infrastructure of Jewish life in the country.)

Rabbi Lau said, "Reb Berel, how old are you?"

"I'm 86 years old."

"What do you do for a living?"

"I'm a butcher, but I have not seen a piece of meat in years."

"Reb Berel, the Russians won't care if you leave. I made some connections here. Let me work on it tonight and tomorrow you will join me on the flight back to Eretz Yisroel, to Israel. You'll be out of the pit for good."

The old man lets out a loud krecthz, a sigh. "Oh to see Yerushalayim; to touch the Western Wall; to breathe the air of our homeland. It is a dream come true. What I wouldn't do to kiss the land of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob."

And then Berel stopped short, and continued: "How much can a person think only of himself? I have one daughter and she married out, a Russian gentile. They don't live near Moscow. She has two children. Two young Jewish boys. One is nine years old and the other one is seven years old. They are my grandchildren, my ainiklach. Once a month my daughter brings my grandchildren to visit their zaide. That day is so dear to me. I get dressed up in my Shabbat clothes and I place one grandson on one knee, the second grandson on the other knee, and I say with them Shema Yisroel Hashem elokainu Hashem echod. I say with them Torah tziva lanu Moshe. I teach them about Moshe Rabbeinu. I teach them about Shabbos, about Rosh Hashanah, about Pesach. I teach them who they are. I sing with them the melodies I heard from my mother and grandmother; I share with them our story, a story that began thousands of years ago and is still going strong.

"Those two hours a month are the only two hours of Judaism they get and those two hours are the most precious two hours of my entire month. If I leave with you to Israel, who will tell them that they are Jewish? Who will see to it that the chain continues? Who will teach them to be proud to be a Jew?"

Somewhere in the world today, there are two brothers, one 32 and one 30, and they know about their heritage. They know that they are "messengers," that they are part of a chain, because their zaide was willing to sacrifice for them.

A second story:

In April 1943, in the Warsaw ghetto, a Jewish family was conducting a seder in a bunker. It was the first night of Passover when the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising broke out.

A child in the family asked the four questions. And then he continued, “Tatti, can I ask you a fifth question"?

The father said, for sure.

So the boy continued with his fifth question: "Why is our nation different than all other nations? Why have we been targeted for abuse and annihilation?"

His father answered, “The Jewish nation began before any other nation had, and it will survive long after the Third Reich is dead. One cannot understand a story if one does not first know the entire story, from beginning to end, and our story is not over yet…"

"Tatty, I have a sixth question. Next year will I be here to ask you these four questions? Will you be here to answer them?"

And the father said, “I’ll be honest with you, my son. I hope yes, but I am not sure. Yet this I want you to know: There is an expression in the sedur, “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished." So I can promise you that somewhere in the world there will be a Moshele or a Dovidl, a saraleh or a racheleh, asking these four questions to their father and mother."

My dear friends, that little boy and his father perished. But last Passover, at the seder table, 3 million Jewish children turned to their mother's and father's and said, "Tatti, Mammi, I want to ask you four questions…"

My friends, this is why we are all here today. “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished."

Categories

Shemini Atzeres/Simchas Torah 5773

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2012

- |

- 17 Tishrei 5773

- |

- 43 views

The Mule and the Salt

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2012

In the Maternity Ward

It is a surreal scene. No eye remains dry when Yaakov Kroyzer, a Vishnitzer Chassid living in Jerusalem, takes his tallis and covers around 100 infants, newly born babies, in a hospital in the Kiryat Yearim neighborhood in Jerusalem.

On Simchat Torah it is customary that even children receive an aliya to the Torah. In synagogues the world over, all the children are gathered together under a tallis and, together with the adult who received this honor, recite the traditional aliya blessings. So Yaakov Kroyzer decided to take it a step further: He makes a Simchas Torah minyan in the maternity ward in the hospital near his home with all of the new infants under the tallis, as all of them get called up to the Torah each year on Simchat Torah!

Mr. Kroyzer has a tallis 30 feet long, with which he bedecks all of the infants. “I am doing it for more than 20 years,” he related recently in a web interview, “and never did any child cry while under the tallis.”

Before they receive the aliya, he gives his annual victory speech which lasts for 20 seconds: “70 years ago, they murdered one and a half million infants and children. Today, 100 of our children, together with hundreds of thousands of children the world over, are being called up to the Torah. This is our victory.” He then calls up all of the children to their aliya, they read the Torah, and a choir sings the songs “hamalach hagoel,” and “vezakeni legadel banim,” blessing these children with a most beautiful and blessed life. [You may ask your cantor to sing]. Not a single mother and father in the audience retains a dry eye.[1]

But why? Why do we call up our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah, something we do not do all year around?[2]

The Grand Debate

For this, we have to explore a fantastical and enigmatic story in the Talmud.

[Note: We discussed this debate in the sermon of Shabbos Haazenu 5773. If you did it, you can skip straight to the actual debate.]

Some 1900 years ago, during the first century CE, only a few years after the destruction of the second Temple by the Romans in the year 70 CE, a great debate took place between the Jews and the Greeks.

The Talmud[3] recounts the fascinating confrontation that occurred between the Wise Men of Athens and the great sage of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya. Athens was known in the ancient world as the seat of wisdom and philosophy, and its sages saw themselves as the deepest and wisest thinkers of the time. Amongst the sages of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua stood out as the sharpest and most quick-witted, a fearsome debater and a brilliant scholar, though to earn a livelihood he would sell charcoal.[4]

He was a Levite who played music back in the Second Temple[5] (the Levites would perform a daily morning concerto in the Temple) and witnessed its destruction. In the following decades, one of the worst periods in all of our history, Rabbi Yehoshua served as the most prominent spokesman for Judaism and the Jewish people. [6]

So when the Roman Caesar demanded to test who was wiser—the Jews or the Greeks—Rabbi Yehoshua was the clear choice to represent the Torah of Israel.

A Conflict of Riddles

Sixty sages of Athens challenged the singular Jewish sage and the battle of wits began. The Talmud records the back and forth between these sages, that took the form of a cryptic exchange of riddles. The Athenian scholars would throw a challenge in front of Rabbi Yehoshua, and Rabbi Yehoshua would come back with an answer each time, usually in the form of a counter-question. Part of the exchange went like this.

בכורות ח, ב: ורצוצא דמית מהיכא נפיק רוחיה? מהיכא דעל נפק

The sages of Athens asked: "If a chick dies while in the egg, before the egg is hatched [and it is sealed from all sides], from where does its soul escape?" Rabbi Yehoshua's response: "The soul escapes through the same place it entered [into the sealed egg]."

משרא דסכיני במאי קטלי בקרנא דחמרא ומי איכא קרנא לחמרא ומי איכא משרא דסכיני

They further asked, "How do you harvest a field of knives?” Rabbi Yehoshua answered: "You use a donkey's horn." The elders: "But donkeys do not have horns!" Rabbi Yehoshua: "And knives do not grow in a field!"

Each one of these exchanges—and there were many of them—begs explanation. What do these bizarre questions really mean, and what lies behind the sharp answers? What wisdom is being displayed here?

The various Talmudic commentaries all agree that the conversations between the Rabbi and the Greeks were allegorical. They were discussing lofty issues of the spirit, the meaning of life and death, G-d's role in the universe, human destiny, the meaning of existence, the concept of the “chosen people,” the cardinal principles of Judaism. They spoke in symbolic terms, the language of wise men, and their words are not to be taken literally.

Salting Salt

But today I want to discuss the one of their other absurd exchanges.

מילחא כי סריא, במאי מלחי לה? אמר להו בסילתא דכודניתא. ומי איכא סילתא לכודנתא? ומילחא מי סרי.

[תרגום ללשון הקודש: (אמרו לו) מלח שמסריח, במה מולחים אותו (כדי לשומרו)? אמר להם, בשליה של פרדה. אמרו לו, וכי יש שליה לפרדה? אמר להם: וכי מלח מסריח?]

They asked him, "When salt gets spoiled, what do we use to preserve it?" His response: "We use the afterbirth of a mule." (This is the embryonic sac which shelters and preserves the developing fetus.) "Do mules have afterbirth?" they asked. [A mule cannot give birth.] "Does salt spoil?" he retorted.

Is this an intelligent conversation between the representatives of the house of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the representative of the Torah of Israel? What are they asking and what is Rabbi Yehoshua answering?

In truth, this absurd exchange symbolized a profound debate—one that endured for thousands of years and rages to this very day. It confronts the important question: What is the relevance of Torah and Judaism in the modern world?[7]

Time To Update the Religion

When the Elders of Athens spoke about salt, they were referring to Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People. They considered that this preservative had spoiled; that it had become rancid, obsolete and irrelevant.

A student once prepared a thesis. The professor wrote on the manuscript that it is both good and original, but then proceeded to fail the student. When the student wondered why he failed, the teacher replied: "The manuscript is both good and original, but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good."

Judaism, the Greeks maintain, is old, very old; the Torah is not an original work written in this century and it needed a tune-up. After all, those were the glorious days of Greek culture, and even many Jews were seeing the Torah as being old-fashioned. Rather than observe Shabbos, they wanted to join the Greek Gymnasiums. Rather than study Torah, they wanted to study Greek philosophy. Rather than sit in a Sukkah, shake a lulav or put on tefilin and daven, they gravitated to Zeus and Olympus, to Homer, Socrates and Plato.

It was time, said the Elders of Athens, to salt the salt. The salt was not old and sour. It was time to change the Torah in order to keep it in the spirit of the day and ensure its popularity. It was time to make some reforms to Judaism. Judaism was ready for an upgrade, for iPhone 5, it needed some cosmetic and substance changes, to make it more fresh, exciting and relevant to a new age inspired by Greek esthetics, philosophy, culture, athleticism, art, drama and literature. Mikvah, tefilin, kosher, Torah study, Torah education, Shabbos candles, Mezuzah, a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashanah, crunchy matzah, the laws of modesty, and the 613 Mitzvos of Torah desperately need a make over. In one word, the salt needs to be salted.

The Mule

Rabbi Yehoshua replied that they should use the afterbirth of a mule. It was a brilliant reply astonishing in its vision, truth and in the method he conveyed such a profound truth. What is a mule? The hybrid offspring of a female horse and a male donkey. At first sight, a mule seems like an awesome animal; it is strong, sure-footed, resistant to disease, and long-lived. By taking elements of the donkey and of the horse, we seem to have the best of both worlds. It has been claimed that mules are "more patient, sure-footed, hardy and long-lived than horses, and they are considered less obstinate, faster, and more intelligent than donkeys."[8] What an awesome combination. It’s just like a Hellenized, modernized Judaism – hybridizing the two cultures in order to have the best of both worlds.

There’s just one problem. Mules can’t breed. They are sterile.

Rabbi Yehoshua was saying: If you try to alter Judaism, to “update” it and combine it with the latest fads, it will look great, and it will doubtless be very popular, the new show in town. But it won’t last. It’s not authentic and it can’t perpetuate. When the sages of Athens explained to him that mule is sterile, Rabbi Yehousha responded, that salt cannot go rancid. Torah, the preservative of the Jewish People, will continue to preserve them, as long as it is left pure and unadulterated.

Torah is salt and salt does not get rancid. It will endure forever, because it is rooted in the source of all life and history, in the Divine. Torah is always relevant because its truths span and pervade all of history, all cultures, all milieus, all circumstances. When we attempt to present a new Judaism, less ancient and more modern, it may be appealing short term. But it will prove sterile in the long term. It will not last. The grandchildren will be lost.

The Results

Was Rabbi Yehoshua right?

1900 years later, we know the answer. Samuel Clemens, popularly known as Mark Twain, famously wrote: "The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, and then passed away. The Greek and the Roman followed. The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?"

What is more, all movements within Judaism which have advocated (as a philosophy) that we alter the Torah and its mitzvos, in order to make it more palpable and appealing to the youth, have become sterile. They perhaps had good intentions, they wanted to preserve Judaism, but their preservatives have proven counter-productive: You don’t try to preserve salt with superficial preservatives. Salt itself is its own best preservative!

The secret of Judaism lay not in the fact that it addresses the fad of the day, that it accommodates the political sentiment of the hour; that it speaks of the new dress design or the latest TV series. The true power of Judaism lay in the fact that it addresses the transcendent needs, yearnings and passions of the human being, truths that transcend time and space, needs that are timeless, aspirations that are eternal.

Shabbas refreshed souls and sanctified homes 3,000 years ago, and it still does so today; tefilin synchronized minds and hearts to our mission in life 2000 years ago and it still does so today; mikvah gave intimacy its holiness and freshness 1000 years ago, it still does so today; Torah study gave moral vision and spiritual inspiration 500 years ago, it still does so today.

When I put on tefillin in the morning, I know that these very same tefillin were donned by Jews in Eretz Israel in 1200 BCE; by Jews in Babylonia in 500 BCE; by Jews in Iran in 100 CE; by Jews in Spain in 1000; by Jews in Poland and Austria in 1600; by my great-great-grandparents in Lithuania in 1850; by Jews in Auschwitz in 1943; and by millions of Jews from Sydney to Los Angeles in 2012.

If Moses and Aaron walk in today to [name the main business center district of your city], they will recognize almost nothing. If they enter our shul today, they will be familiar with so much: the same mezuzah, the same tefillin, the same talit, the same Torah scroll, the same Sukkah, the same shofar, the same lulav and esrog; 3,324 years, and the same Torah that Moses taught his children, we are teaching our children. [9]

The Story of Henryk-Abraham[10]

Henryk was very young in 1945, when the War ended and solitary survivors tried frantically to trace their relatives. He had spent what seemed to be most of his life with his nanny, who had hidden him away from the Nazis at his father's request. There was great personal risk involved, but the woman had readily taken it, as she loved the boy.

All the Jews were being killed, and Henryk's nanny did not think for a moment that the father, Joseph Foxman, would survive the infamous destruction of the Vilna Ghetto. He would surely have been transferred to Auschwitz — and everyone knew that nobody ever came back from Auschwitz. She therefore had no scruples about adopting the boy, having him baptized into the Catholic Church and taught catechism by the local priest.

The nanny saved his life—but also taught him to spit on the ground when a Jew walked by.

It was Simchat Torah when his father came to take him. The heartbroken nanny had packed all his clothing and his small catechism book, stressing to the father that the boy had become a good Catholic. Joseph Foxman took his son by the hand and led him directly to the Great Synagogue of Vilna. On the way, he told his son that he was a Jew and that his name was Avraham.

Not far from the house, they passed the church and the boy reverently crossed himself, causing his father great anguish. Just then, a priest emerged who knew the boy, and when Henryk rushed over to kiss his hand, the priest spoke to him, reminding him of his Catholic faith.

Everything inside of Joseph wanted to drag his son away from the priest and from the church. But he knew that this was not the way to do things. He nodded to the priest, holding his son more closely. After all, these people had harbored his child and saved the child's life. He had to show his son Judaism, living Judaism.

They entered the Great Synagogue of Vilna, now a remnant of a past, vibrant Jewish era. There they found some Jewish survivors from Auschwitz who had made their way back to Vilna and were now rebuilding their lives and their Jewish spirits. Amid the stark reality of their suffering and terrible loss, in much diminished numbers, they were singing and dancing with real joy while celebrating Simchat Torah.

Only 3,000 of Vilna's 100,000 Jews remained.

Avraham stared wide-eyed around him and picked up a tattered prayer book with a touch of affection. Something deep inside of him responded to the atmosphere, and he was happy to be there with the father he barely knew. He held back, though, from joining the dancing.

A Jewish man wearing a Soviet Army uniform could not take his eyes off the boy, and he came over to Joseph. "Is this child... Jewish?" he asked, a touch of awe in his voice.

The father answered that the boy was Jewish and introduced his son. As the soldier stared at Henryk-Avraham, he fought to hold back tears. "Over these four terrible years, I have traveled thousands of miles, and this is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all this time. I did not see a single Jewish child. They were all murdered. This is the first live Jewish child I have come across in all these years... Would you like to dance with me on my shoulders?" he asked the boy, who was staring back at him, fascinated.

The father nodded permission, and the soldier hoisted the boy high onto his shoulders. With tears now coursing down his cheeks and a heart full of real joy, the soldier joined in the dancing.

"This is my Torah scroll," he cried, as he danced with the five year old Jewish boy.

The Abraham in our story you all heard of: His name is Abe Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League.

The Reunion

But this is not the end of the story.

For 65 years, the boy and the soldier carried that moment in their heads and hearts. Unknown to each other, they told the story to family and friends.

But then something happened. The Jewish composer Abie Rotenberg put together a song, "The Man From Vilna," about the incident with a Michigan rabbi dancing with a Jewish boy. Foxman heard the song and he learned that the Jewish Soviet soldier was a man named Goldman, still alive and living in the United States.

Two years ago, they met and embraced for the first time since 1945. As it turns out, the Soviet soldier is 93 year old Rabbi Leo Goldman from Oak Park, Detroit, an Orthodox rabbi and an educator

The two men hugged and talked and recited the blessing of “Shecheyanu vekeymanu veheganu lizman hazeh.”[11]

Dance With Your Children

That is why we call up all of our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah—because this is what captures the reason for our never ending celebration of the Torah: In a world where every fad turns into a mule, we celebrate the “salt” which never grows old, sour or rancid. It is our children that demonstrate to us the eternal value of Torah.

Friends, we are not in Vilna in 1945. We are, thank G-d, living in freedom. Abe Foxman’s life was changed because of that single dance. We ought not to deprive our children of that dance.

Let us bring our children, grandchildren and friends for our Simchat Torah celebration. And let us dance away with them. Life up your children—or your friend’s children—or your grandchildren on your shoulders and dance with them. Dance and dance. Let us dance with millions of Jews who will all dance with us on this Simchas Torah celebrating the Divine gift of Torah which becomes more fresh, more relevant, and more exciting each year.

Let us dance away and commit ourselves this coming year to embrace the Torah in our lives, by increasing in our study of Torah. Join a Torah class. Study Torah on your own. But don’t let the ultimate preservative of history slip through your fingers.

[As we are about to say yizkor, we remember what our loved ones have given us, the “salt” that passed on to us, and we commit to share that eternal “salt” with our children.]

[1] For the full story and photos, see: http://www.bhol.co.il/article_old.aspx?id=33026

[2] The Malbushei Yom Tov gives this reason:

שגם הם ידעו, שיש להם אות וחלק בתורה ולחנכם במצוות ולשתפם בשמחת התורה. מצאתי על קלף, ש"בחיי" (רבנו "בחיי", מחבר הפירוש תורה) כתב למחות [נגד המנהג] לזרוק פירות לנערים בשמחת תורה; אבל יש במדרש, שזה היה אומר המן למלך (אחשורוש) על היהודים. אם כן מנהג קדמון הוא. ואולי (מחה רבינו בחיי על מנהג זה כיון) שראה ה"בחיי" בימיו, שנוהגים בזה ריקות והוללות. (מלבושי יום טוב).

[3] Bechoros 8b

[4] Talmud Berachos 28a

[5] Talmud Erkin 11

[6] See Talmud Chagigah 5b

[7] The following explanation is based on Maharsha to Bechoros 8b and Sefer Dorash Moshe derush 32. Cf. Chidushei Agados Maharal, Perus HaGra, and Likkutei Mahran for alternative explanations to this exhchange.

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mule footnote 3

[9] You can share these two stories:

I want to share with you a story that I heard from the former chief rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Israel Meir Lau. In 1989, when Gorbachev first introduced Glasnost to the Soviet Union, as a gesture to the Jewish community he invited an international delegation of rabbis to visit Moscow. They were to spend six days with the Jewish community. Rabbi Lau was one of the rabbis selected. They spoke in various synagogues, gave encouragement and inspired many with hope for tomorrow. On their last night in the Moscow shul, an old man named Berel asked Rabbi Lau if he could escort him to his hotel. Rabbi Lau agreed. The shul was about a half hour walk from the hotel.

Reb Berel began to cry. "You come here, you teach, you sing with us, you have Shabbos with us, you lift us up so high, and then you leave us. You go home and we're here alone, back in the pit of despair again. (Remember, that in those days shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, there was absolutely no infrastructure of Jewish life in the country.)

Rabbi Lau said, "Reb Berel, how old are you?"

"I'm 86 years old."

"What do you do for a living?"

"I'm a butcher, but I have not seen a piece of meat in years."

"Reb Berel, the Russians won't care if you leave. I made some connections here. Let me work on it tonight and tomorrow you will join me on the flight back to Eretz Yisroel, to Israel. You'll be out of the pit for good."

The old man lets out a loud krecthz, a sigh. "Oh to see Yerushalayim; to touch the Western Wall; to breathe the air of our homeland. It is a dream come true. What I wouldn't do to kiss the land of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob."

And then Berel stopped short, and continued: "How much can a person think only of himself? I have one daughter and she married out, a Russian gentile. They don't live near Moscow. She has two children. Two young Jewish boys. One is nine years old and the other one is seven years old. They are my grandchildren, my ainiklach. Once a month my daughter brings my grandchildren to visit their zaide. That day is so dear to me. I get dressed up in my Shabbat clothes and I place one grandson on one knee, the second grandson on the other knee, and I say with them Shema Yisroel Hashem elokainu Hashem echod. I say with them Torah tziva lanu Moshe. I teach them about Moshe Rabbeinu. I teach them about Shabbos, about Rosh Hashanah, about Pesach. I teach them who they are. I sing with them the melodies I heard from my mother and grandmother; I share with them our story, a story that began thousands of years ago and is still going strong.

"Those two hours a month are the only two hours of Judaism they get and those two hours are the most precious two hours of my entire month. If I leave with you to Israel, who will tell them that they are Jewish? Who will see to it that the chain continues? Who will teach them to be proud to be a Jew?"

Somewhere in the world today, there are two brothers, one 32 and one 30, and they know about their heritage. They know that they are "messengers," that they are part of a chain, because their zaide was willing to sacrifice for them.

A second story:

In April 1943, in the Warsaw ghetto, a Jewish family was conducting a seder in a bunker. It was the first night of Passover when the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising broke out.A child in the family asked the four questions. And then he continued, “Tatti, can I ask you a fifth question"?

The father said, for sure.

So the boy continued with his fifth question: "Why is our nation different than all other nations? Why have we been targeted for abuse and annihilation?"

His father answered, “The Jewish nation began before any other nation had, and it will survive long after the Third Reich is dead. One cannot understand a story if one does not first know the entire story, from beginning to end, and our story is not over yet…"

"Tatty, I have a sixth question. Next year will I be here to ask you these four questions? Will you be here to answer them?"

And the father said, “I’ll be honest with you, my son. I hope yes, but I am not sure. Yet this I want you to know: There is an expression in the sedur, “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished." So I can promise you that somewhere in the world there will be a Moshele or a Dovidl, a saraleh or a racheleh, asking these four questions to their father and mother."

My dear friends, that little boy and his father perished. But last Passover, at the seder table, 3 million Jewish children turned to their mother's and father's and said, "Tatti, Mammi, I want to ask you four questions…"

My friends, this is why we are all here today. “ki besham kodsecah nishbata shelo yechbe naro leolam vaed," “You have taken an oath that Israel's flame will never be extinguished."

- Comment

Class Summary:

It is a surreal scene. No eye remains dry when Yaakov Kroyzer, a Vishnitzer Chassid living in Jerusalem, takes his tallis and covers around 100 infants, newly born babies, in a hospital in the Kiryat Yearim neighborhood in Jerusalem, giving them all an aliya for Simchas Torah. Before the aliya, he gives a 20-second speech: 70 years ago, infants like yourself were sent to the gas chmabers. Today, you are under a tallis being called up to the Torah, celebrating our heritage, and perpetuating our eternal values and hopes.

Why do we call up our children to the Torah on Simchas Torah, something we do not do all year around?

For this, we have to explore a fantastical and enigmatic story in the Talmud, recording a debate 1900 years ago between the sages of Athens, the great wise men of Greece, and the Jewish sage Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya. They asked him, "When salt gets spoiled, what do we use to preserve it?" His response: "We use the afterbirth of a mule." (This is the embryonic sac which shelters and preserves the developing fetus.) "Do mules have afterbirth?" they asked. [A mule cannot give birth.] "Does salt spoil?" he retorted. And he won the debate.

Is this an intelligent conversation between the representatives of the house of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the representative of the Torah of Israel? What are they asking and what is Rabbi Yehoshua answering?

In truth, this absurd exchange symbolized a profound debate—one that endured for thousands of years and rages to this very day. It confronts the important question: What is the relevance of Torah and Judaism in the modern world?

It was Simchat Torah when his father came to take him—his little boy who was raised by the Catholics throughout the Holocaust. The heartbroken Christian nanny had packed all his clothing and his small catechism book, stressing to the father that the boy had become a good Catholic. Joseph Foxman took his son by the hand and led him directly to the Great Synagogue of Vilna. On the way, he told his son that he was a Jew and that his name was Avraham. In the shul, it was a Soviet soldier who lifted him up on his shoulders, dancing with him, crying: This is my Sefer Torah!

And in 2010, the two met again—the soldier and the boy. One turned out to be the head of ADL and the other a prominent Rabbi in Detroit. They both made a resounding Shecheyanu.

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!