Choose Life: Hemingway, Wiesel & Yizkor

”Remember the Soul of My Parents Because I will Donate to Charity”

- October 16, 2016

- |

- 14 Tishrei 5777

Rabbi YY Jacobson

30 views

Choose Life: Hemingway, Wiesel & Yizkor

”Remember the Soul of My Parents Because I will Donate to Charity”

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 16, 2016

Make Sure He's Dead

A couple of Montana hunters are out in the woods when one of them falls to the ground. He doesn't seem to be breathing, his eyes are rolled back in his head. The other guy whips out his cell phone and calls the emergency services. He gasps to the operator: “My friend is dead! What can I do?”

The operator, in a calm soothing voice says: “Just take it easy. I can help. First, let's make sure he's dead.” There is a silence, then a shot is heard.

The guy's voice comes back on the line. He says: “OK, now what?“

The Storm

Sadie has died and today is her funeral. Her husband Nathan and many of

their family and friends are standing round the grave as Sadie's coffin is

lowered into the ground. Then, as is the custom, many of the mourners pick

up some shovels and help to fill the open grave with earth.

But on their way back to the prayer hall, the sky suddenly darkens, rain

starts to fall, flashes of lightening fill the sky and loud thunder rings

out.Nathan turns to his rabbi and says, "Well rabbi, she's arrived alright."

Strange Text of Yizkor

Yizkor, a special memorial prayer for the departed, is recited in the synagogue four times a year, following the Torah reading on the last day of Passover, on the second day of Shavuot, on Yom Kippur, and today—on Shemini Atzeres.

Yizkor, in Hebrew, means "Remember." It is not only the first word of the prayer, it also represents its overall theme. In this prayer, we implore G‑d to remember the souls of our relatives and friends that have passed on.

This is the text of Yizkor: “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher (and we mention his or her Hebrew name and that of his or her mother)—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—who has gone to his [supernal] world, because I will (without obligating myself with a vow) donate charity for his/her sake. In this merit, may his soul be bound up in the bond of life with the souls of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, and with the other righteous men and women who are in Gan Eden; and let us say, Amen.

There are two strange things here. First, why are we asking G-d to “remember” the soul of our father, mother, or other loved ones, when we know He remembers everything? As we say on Rosh Hashanah, “There is no forgetfulness before the throne of Your Glory.” If we cannot forget the soul of someone we have lost, how could G-d forget him or her? After all, G-d created that soul, for sure He does not forget it!

In the stirring words of Isaiah:

The second enigma is the reason we give to G-d for remembering the soul. “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—because I will donate charity for his/her sake.” Really? G-d should remember them because I will give a check to charity? If I don’t give 18 dollars or 1800 dollars to charity G-d might forget them; but since I am giving some charity, therefore G-d shall remember them?

In truth, one question is answered by the other.

Hemingway and Bleich

I want to share with you a fascinating story about a meeting between a young American Rabbi, and arguably the greatest writer of the 20th century.

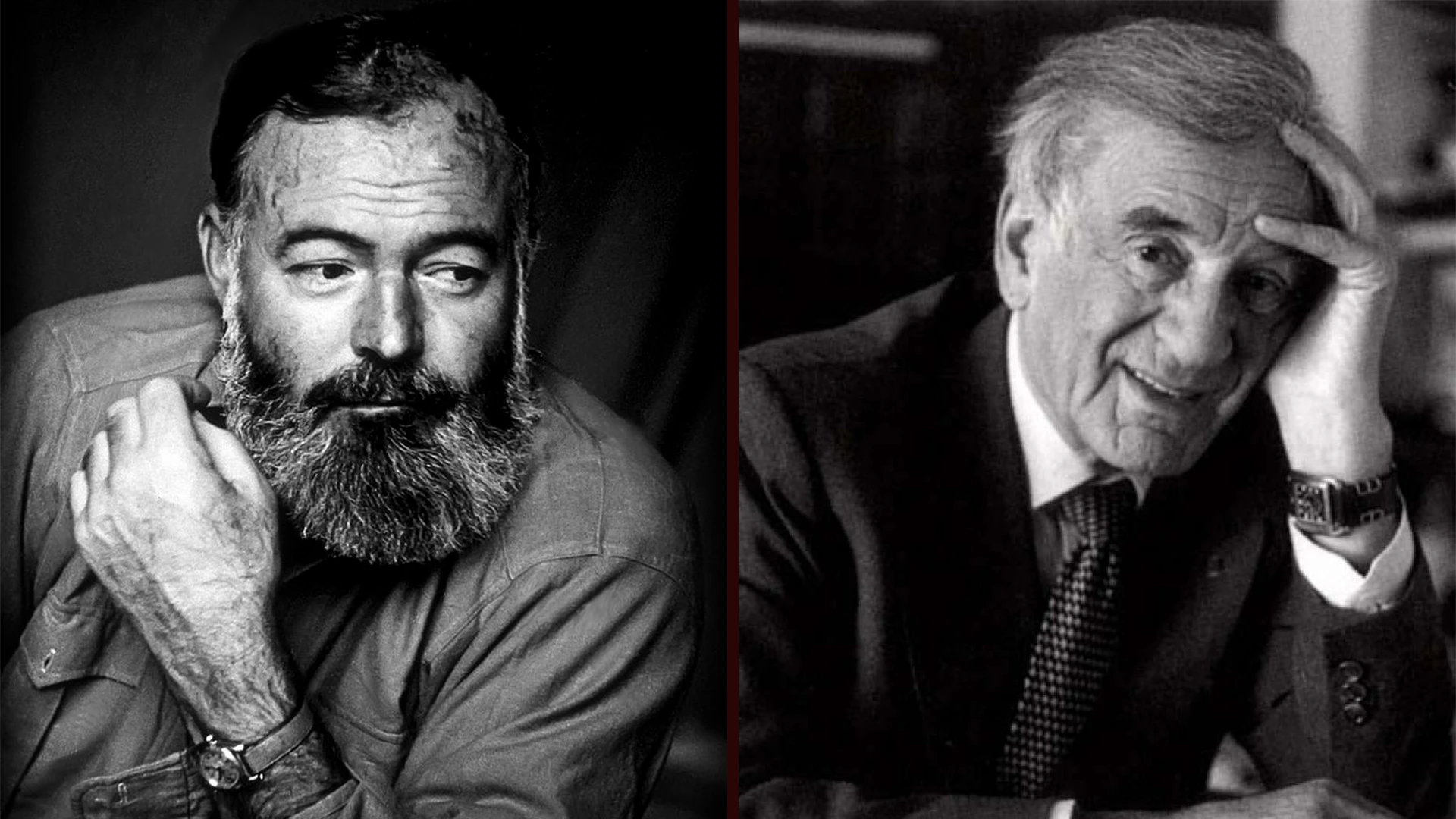

One of the greatest authors in American history, whose works are considered timeless classics of American literature, was Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961). Rabbi Benjamin Blech, who serves today a professor at Yeshiva University in NY, related the following personal episode.[1]

The year was 1956. I had just been ordained and felt I needed a vacation after completing years of rigorous study, to get ordained by the famed Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik. Together with two other newly minted rabbis, we decided on a trip that in those days was considered rather exotic. We chose pre-Castro Cuba as our destination—not too far away, not too costly, beautiful and totally different from our New York City environment.

One day as we drove through Havana and its outskirts, our combination taxi driver/guide pointed out a magnificent estate and told us that this was the residence of the writer, Ernest Hemingway. "Stop the car," we told him. "We want to go in." He shook his head and vehemently told us, "No, no, that is impossible. No one can just come in to visit. Only very important people who have an appointment."

With the chutzpah of the young, I insisted that we would be able to get in and approached the guard with these words: "Would you please call Mr. Hemingway and tell him that three rabbis from New York are here to see him."

How could Hemingway not be intrigued? Surely he would wonder what in the world three rabbis wanted to talk to him about. We held our breaths, and the guard himself could not bElive it when the message came back from the house that Mr. Hemingway would see us.

We were ushered into Hemingway's presence as he sat in his spacious den. What followed, we subsequently learnt, was a verbal volley meant to establish whether it was worthwhile for him to spend any time talking to us. He questioned us about our backgrounds, threw some literary allusions at us to see if we would understand their meaning, asked what we thought was the symbolic meaning of some passages in his A Farewell To Arms—and then after about 15 minutes totally changed his demeanor and spoke to us with a great deal of warmth and friendship.

"Rabbis," he said to us, "forgive me for having been brusque with you at first but before continuing I had to make certain it was worth my while to talk to you. To be honest, I've long wanted to engage a rabbi in conversation. I just never had the opportunity. And now suddenly out of the blue you've come to me."

Hemingway then opened up to us in most remarkable manner. He told us he had a great interest in religion for many years which he pursued privately and never discussed or wrote about. He said during one period of his life he set aside time to study many of the major religions in depth.

He said that after he thought deeply about the different religions he studied, he came to an important conclusion. Fundamentally he realized all religions divide into one of two major categories. There are religions of death and there are religions of life. Religions of death are the ones whose primary emphasis is preparation for an afterlife. This world and its pleasures are renounced in favor of dedicating oneself totally to the world to come. "Obviously," he added, "that isn't for me." What he respects, he continued, is the religion of Judaism which stress our obligations to what we are here for now on earth rather than the hereafter.

With his perceptive mind, he summed up the essence of Judaism perhaps better than most Jews themselves can. Judaism is a religion of life. "Choose life," says the Torah.

Rabbi Bleich continues:

I took the opportunity to compliment Hemingway on his analysis and had the temerity to ask if I might teach him something that would add to his insight. I told him of the biblical law that prohibits the Kohanim, all the members of the Jewish priesthood, from coming into any contact with the dead. If they did so, they would be considered impure. To this day Kohanim cannot enter a funeral chapel with a body inside.

The rabbinic commentators questioned the reason behind this law. The answer that resonates most with scholars is that the Torah wanted to ensure that the priestly class, those assigned to dedicate themselves to the spiritual needs of their people, did not misconstrue their primary function. In all too many religions, the holy men devote themselves almost exclusively to matters revolving around death. Even in our own times, the only connection many people have with a spiritual leader is at a funeral. That is why the Bible forbade the priests from having any contact with the dead—so that they spend their time, their efforts, their concerns and their energy with the living.

Hemingway smiled and thanked me for sharing with him this beautiful idea.

This encounter with Hemingway became all the more poignant when, in just a few years, on July 2, 1961, the man whose hand wrote the books we revere to this day chose to use it to put the barrel of his shotgun into his mouth and commit suicide. Somehow, Hemingway was never able to find a spiritual source on which to lean in order to give him a reason for living. He had taught the world, in his words, "But man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated." And yet, tragically, the biblical ideal to "choose life" that he praised in our meeting could not guide him in the end.

The Watch

But let me tell you know a very different story, about another great author and a great Jew, Holocaust survivor and witness, Eli Wiesel, who died three months ago, in July 2016, at the age of 87.

“The Watch” is the name of an autobiographical tale told by Eli Wiesel in his 1965 book, One Generation After. Wiesel shares the story of his first, and what would be his only, return to the town of his birth, Sighet, Rumania, since the conclusion of World War II.

For his bar mitzvah, Wiesel explains, he had received a beautiful gold watch, a gift he treasured dearly until a few years later when he had turned fifteen, and the Nazis came, followed by the edicts, and then the ghettos, the transports, and eventually the fateful hours just before Passover of 1944 when the 10,000 Jews of Sighet were sent to their death. As the roundups began, but with the darkness of the night yet to come still beyond their sight, Eli and his family began to dig feverishly into the ground in order to bury the jewelry, the candelabras, the family heirlooms – anything and everything of value – in the naive hope that one day they would return to retrieve them. Eli had one and only one possession of value – his bar mitzvah watch – and so like the rest his family, he decided to bury it, three steps from the fence, beneath the poplar tree, to be recovered one day.

And so two days before Passover in 1944, on the night before he and his family were deported to Auschwitz, 15-year-old Eli Wiesel dug a hole in the garden of his home and buried a gold watch his beloved grandfather had given him.

Twenty years and an eternity later, Wiesel returns unannounced to Sighet with the mission of retrieving his cherished watch. It is the middle of the night as Eli secretly and cautiously sneaks into the yard of his childhood, careful not to wake the family sleeping in the home that was once his. He retraces his steps to the exact location, and using his bare hands, begins to scratch and dig into the frozen ground as minutes, or maybe it was hours, pass. Suddenly his fingers hit something hard and metallic and he exhumes the box containing the relic from his past, the only remaining symbol of all that had been—and went up in flames. The intervening years had not been kind to the watch: it was rusty and covered with dirt. Eli nonetheless touches it, caresses it, and raises it lovingly to his lips. At that moment Wiesel resolves to bring it to the best jeweler in the world to recover the luster it once had.

He want to take with him this one last item of his innocent youth—before it was all destroyed.

Sensing the rising of the sun and coming of dawn, Wiesel hurriedly stuffs the watch into his pocket and runs out of the garden and courtyard. He does not want to be caught. He is halfway down the street when – inexplicably – he stops dead in his tracks. He does an about face, retraces his steps to that poplar tree in the garden, and in his words, “as at Yom Kippur services,” kneels down, places the watch back into the box, the box back into the hole, and then proceeds to once more fill up the hole with earth.

The story ends with Wiesel wondering to himself why he did what he did. Walking away, he imagines hearing the voices of his childhood village along with the tick-tock of the just buried watch. Leaving his village never to return, Wiesel concludes: “Since that day, the town of my childhood has ceased being just another town. It has become the face of the watch.”[2]

Eli Wiesel, as is his nature, leaves the rest of the story to our imagination. And in my imagination, this little story captures the distinction between Hemingway and Wiesel—where one man haunted by the horrors of his past, who lost much his family to the Germans, went on to inspire people to live and love, and the other felt compelled to put an end to his tortured and deep soul.

It also captures the essence of Yizkor.

The Soul Needs You

Judaism believes in afterlife, as does most every religion in the world. A soul never dies; it lives for eternity. Our life here on earth is but a small part of our soul’s journey. The soul, by its very nature, is not physical, it is not made up of physical stuff, and no physical ailment and death can obliterate it.

And yet, Judaism teaches that the most important experience of the soul is the time it spends down here in this world. For the ultimate purpose of creation was not heaven, but earth. G-d wants humanity to build a fragment of heaven on earth, to create a world of goodness and holiness.

Hemingway put it so well, that Judaism is a “religion of life.” But it goes even deeper than he imagined. Even after the soul leaves us, it never disconnects from us. Not only is the soul eternally alive, but the soul is also eternally connected to its loved ones here on earth. The soul craves that its ideals, dreams, aspirations and good deeds should be continued here on earth, because the soul knows that the objective of all of creation was to transform our world into a

Divine abode. So as high up as the soul goes, it never stops to look down and see how we are continuing its life. The soul craves to continue living here through us—through our lives and deeds! What I do down here in my life on earth impact profoundly the soul of my loved one, though I can’t see him, hear him, touch him, feel him or kiss him, or her. When I give charity down here in this world, I create an impact not only for the person I gave the charity for, but also for the soul of my loved ones who may be gone for decades.A man once shared this:

“I lost my son, and since his death just could not go on. I hoped that time would heal, but everyday was just as the day of the funeral. I searched amongst the wise and saintly leaders for comfort and direction but found none. Tonight, I have come to the Lubavitcher Rebbe for guidance and comfort. The Rebbe said to me as follows, ‘If your son was well but taken away that you could not see him, would you be able to live with that?’ To which I responded, definitely, it would be painful, however, it would be livable.’ The Rebbe then continued, “and if you were told that you may send your son care-packages and be guaranteed that he would receive them and that they would be of good use, would you send packages?’ ‘Why, of course,’ I replied. The Rebbe than looked me deep in my eyes and said, ‘I assure you that your son is okay in Heaven, and I assure you that your care-packages will reach him and be of good use. Send him a Kaddish, Mishnayos, and charity.’”

“For the first time since the death of my son, some despair was lifted from my heart,” concluded the man. “Yes, it is very painful that I cannot physically see him, hear him, and hug him, but I know now that he is okay, and a new form of communication can exist.”

So G-d remember each end every soul, even without our saying yizkor and asking Him not to forget. A mother does not forget her child and G-d forgets no soul. When we ask G-d to remember the soul of our loved ones it is like the Torah says, “G-d remembered Rachel,” or when G-d says, “I remember the Jews in Egypt,” or, “I will remember the covenant with Jacob.” It is not that He forgot it and He now reminds Himself. It means that He will tune-in tad respond to the particular needs of this soul, to grant the soul all it needs, including what the souk asks for in terms of its loved ones.

This is the reason we say in Yizkor, “Remember my father or my mother because I will be giving charity in their merit.” By me giving charity for their sake, I am allowing their soul to be empowered, invigorated, inspired, elevated and nurtured. My mitzvah, my tzedakah, that I do for the soul, has such a powerful impact, that G-d Himself “remembers” and responds to every single needs of this soul.

There is nothing that has such a positive impact on the soul like the good deeds we do down here. For this is the space where all actions happens.

Thus, we remember our loved ones not only by missing them, crying for them, and yearning for them. Of course, that is natural. But the deepest and most authentic way of remembering them is by being here for them, by showing up for them. And how can we be here for them? By doing things that they would have done had they been living; and now they need us to do it. And when we do it—it brings them infinite joy and helps them in infinite ways.

This is one of the great ideas in the Jewish religion[3]—the ultimate “religion of life,” that the small, concrete deeds of a person living here on earth creates a powerful impact on a neshamah, a soul, that is not only 40,000 miles above earth, but in a completely different zone, so to speak. Our acts of charity, or learning Torah, or prayer, or other mitzvos, causes G-d himself to connect to that particular soul in a unique and special way and fulfill its needs and wants.

I think this is what Eli Wiesel felt when he returned the watch to the hole in the earth. He felt that the watch, and all it represented, belonged to a past world, and he did not want to take it along with him. You must remember my past, but you can’t take it along wherever you go, because then you may remain stuck in your past. And the main calling of your past must be to continue living. What our loved ones want most is that we continue moving, living and growing. If we just yearn for the past, we compromise not only our happiness, but also their happiness.

A Journey From Iran

In her introduction to her book “Life is a Gift,” Dr. Miriam Adahan, a therapist and author, relates that when she moved to Israel from the US, in 1981, they lived for a while in an absorption center. There, she writes, I became friendly with a young widow with four children who had come from Iran a year and a half before in 1979. Although she lived in a tiny, one room apartment and worked as a clerk in the local post office, she had this regal dignity which hinted at a refined background.

As our eleven-year-old daughters became best friends, the story of her previous life had emerged.

In Iran, they had been very wealthy, with servants, beautiful cars and expensive vacations abroad. Then came the overthrow of the Shah in 1979 by the Aytalah Chuemeni, and the reign of terror against the Jews began. One day, a gang of thugs entered her husband's rug store and shot him dead, they defaced the walls with his blood, proclaiming him an agent of the Shah.

Informed of the awful tragedy, the grief stricken widow knew she had to leave Iran immediately to save herself and her children.

Desperately trying to stay in control she contacted a man who was known to be helping Jews escape over the treacherous mountains through Turkey.

Since unauthorized travel was forbidden and the sale of any household items might arouse suspicions she had to leave most of her wealth behind. She could not tell anyone of her plans, not even her children. She could not pack suitcases, as neighbors might see and report her to the police.

Trembling, and trying not to let her terror show, she took whatever little cash and jewelry she had on hand, and telling her children that they were going shopping, left the home, never to return.

In the darkness of night, they met their guide at the edge of Teheran. Handing over most of her money and jewelry, the harrowing nightmare began for this brave widow and her four children, and the youngest a girl of three.

For The first few days, they spent eighteen hours at a time on camels. The pain they suffered was so excruciating that they often felt they would collapse.

The mother sustained permanent damage to her back. But each time they complained, the guide yelled, took out his revolver and said that he would shoot them if they said another word.

They had no choice but to go on.

By day, the sun scorched them, at night, they froze. As the mountains got steeper, they switched to riding donkeys. Often, the road was so narrow that one wrong move and the donkey and its rider would plunge to the abyss below. The mother said, we cannot continue… we are going back…but the guide yelled, took out his revolver and threatened to shoot them if they said another word….there is no going back he said.

Once, in their rush to cross a freezing stream, they all lost their shoes in the mucky water. When they reached the other side they had to walk barefooted on prickly cactus plants and sharp stones.

Wincing in pain, as the thorns and pebbles cut into their flash. With pain and fatigue, the mother and her older son took turns carrying the youngest child.

At another point they had to make their way across a flimsy bridge made of ropes and wooden slats which stretched between two mountain peaks and spanned and deep ravine. The ropes looked as though they could barely hold their own weight, let alone a group of terrified Jewish refugees. Looking down into the abyss below, the mother froze into utter terror, crying out that she could not possibly go on.

Again, their guide took out his gun and threatened her and her children with death if they did not move. Taking her three year old by the hand, she forced herself to grab the ropes, fueled by anger towards the Iranian guide who urged them on so gruffly.

After two-and-a-half weeks of this continuous torture, the small group of Jewish refugees arrived at the Turkish border. There, the guide, who had always been so harsh, so cruel and unsympathetic- suddenly embraced each child warmly and said to the mother:

"Before I leave you, I want to tell you that I, too, am Jewish. I'm sorry I had to be so rough. But if I had been nice to you, you wouldn't have made it. I had to scare you, I had to threaten you, I had to intimidate you into moving, or you would not have been able to go on."

And with tears in his eyes he said, "I’m so proud of each and every one of you. You are all true gibborim—heroes to have made it to this point of freedom." With that, he turned and left to go back in the direction of Iran, while this family eventually made it to Israel and started a new life.

Continue the Journey

After reading this story, I thought to myself, that like this heroic family, we, too, are on a journey which is often treacherous and filled with challenges and pain. As we say yizkor, we recall in sadness and fondness those who left us and here with us anymore. It’s painful, it’s sad, especially for the young members of our families who will never know these people.

And yet, as yizkor reminds us, our main duty to our loved ones is to continue the journey here on earth and not to stop moving. And one thing we know for sure: Our guide always loves us, even when He challenges us, and that all the difficulties we go through must empower us to continue our journey and mission.

Hemingway said: The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places. Sadly, he could not find that strength in the broken places. Yet the “religion of life” beacons us to remember the awesome power that lay in our living a life here on earth saturated with Torah and Mitzvos and good deeds, one that even souls gone for millennia look towards in order to be uplifted and elevated.[4]

[2] One Generation After, pp. 60–65

[3] This was a unique expression the Rebbe used in his talk on 20 Av, 5729 (1969). It was a rare expression: “This seems to be one of great novel ideas of the Jewish religion and the Jewish faith that we can impact a soul above.”

[4] This sermon is based on Sichas 20 Av 5729; Sichas Shabbos Yisro 22 shevat 5749.

- Comment

Class Summary:

There are two strange things about the text of Yizkor. Why are we asking G-d to “remember” the soul of our father, mother, or other loved ones, when we know He remembers everything? If we cannot forget the soul of someone we have lost, how could G-d forget him or her?

The second enigma is that we say, “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—because I will donate charity for his/her sake.” Really? G-d should remember them because I will give a check to charity? If I don’t give 18 dollars or 1800 dollars to charity G-d might forget them; but since I am giving some charity, therefore G-d shall remember them?

For this I will share with you a fascinating story about a meeting between a young American Rabbi, and arguably the greatest writer of the 20th century. Hemingway loved the words the rabbi told him about the value of life, but it could not stop him from taking his own life.

Contrast this with another story about another great author. Two days before Passover in 1944, on the night before he and his family were deported to Auschwitz, 15-year-old Eli Wiesel dug a hole in the garden of his home and buried a gold watch his beloved grandfather had given him for his bar mitzvah.

Twenty years and an eternity later, Wiesel returns unannounced to Sighet with the mission of retrieving his cherished watch. It is the middle of the night as Eli secretly and cautiously sneaks into the yard of his childhood, careful not to wake the family sleeping in the home that was once his. He discovers the watch but then decides to do something very strange with the watch.

The story of a Jewish family that made its way from Iran to Israel in a most treacherous journey, and the advice the Lubavitcher Rebbe gave a bereaved father, captures the primary message of yizkor. The greatest thing I can do for my loved one who is not here any longer is to continue their ideals, dreams and good deeds here on earth.

Make Sure He's Dead

A couple of Montana hunters are out in the woods when one of them falls to the ground. He doesn't seem to be breathing, his eyes are rolled back in his head. The other guy whips out his cell phone and calls the emergency services. He gasps to the operator: “My friend is dead! What can I do?”

The operator, in a calm soothing voice says: “Just take it easy. I can help. First, let's make sure he's dead.” There is a silence, then a shot is heard.

The guy's voice comes back on the line. He says: “OK, now what?“

The Storm

Sadie has died and today is her funeral. Her husband Nathan and many of

their family and friends are standing round the grave as Sadie's coffin is

lowered into the ground. Then, as is the custom, many of the mourners pick

up some shovels and help to fill the open grave with earth.

But on their way back to the prayer hall, the sky suddenly darkens, rain

starts to fall, flashes of lightening fill the sky and loud thunder rings

out.

Nathan turns to his rabbi and says, "Well rabbi, she's arrived alright."

Strange Text of Yizkor

Yizkor, a special memorial prayer for the departed, is recited in the synagogue four times a year, following the Torah reading on the last day of Passover, on the second day of Shavuot, on Yom Kippur, and today—on Shemini Atzeres.

Yizkor, in Hebrew, means "Remember." It is not only the first word of the prayer, it also represents its overall theme. In this prayer, we implore G‑d to remember the souls of our relatives and friends that have passed on.

This is the text of Yizkor: “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher (and we mention his or her Hebrew name and that of his or her mother)—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—who has gone to his [supernal] world, because I will (without obligating myself with a vow) donate charity for his/her sake. In this merit, may his soul be bound up in the bond of life with the souls of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, and with the other righteous men and women who are in Gan Eden; and let us say, Amen.

There are two strange things here. First, why are we asking G-d to “remember” the soul of our father, mother, or other loved ones, when we know He remembers everything? As we say on Rosh Hashanah, “There is no forgetfulness before the throne of Your Glory.” If we cannot forget the soul of someone we have lost, how could G-d forget him or her? After all, G-d created that soul, for sure He does not forget it!

In the stirring words of Isaiah:

The second enigma is the reason we give to G-d for remembering the soul. “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—because I will donate charity for his/her sake.” Really? G-d should remember them because I will give a check to charity? If I don’t give 18 dollars or 1800 dollars to charity G-d might forget them; but since I am giving some charity, therefore G-d shall remember them?

In truth, one question is answered by the other.

Hemingway and Bleich

I want to share with you a fascinating story about a meeting between a young American Rabbi, and arguably the greatest writer of the 20th century.

One of the greatest authors in American history, whose works are considered timeless classics of American literature, was Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961). Rabbi Benjamin Blech, who serves today a professor at Yeshiva University in NY, related the following personal episode.[1]

The year was 1956. I had just been ordained and felt I needed a vacation after completing years of rigorous study, to get ordained by the famed Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik. Together with two other newly minted rabbis, we decided on a trip that in those days was considered rather exotic. We chose pre-Castro Cuba as our destination—not too far away, not too costly, beautiful and totally different from our New York City environment.

One day as we drove through Havana and its outskirts, our combination taxi driver/guide pointed out a magnificent estate and told us that this was the residence of the writer, Ernest Hemingway. "Stop the car," we told him. "We want to go in." He shook his head and vehemently told us, "No, no, that is impossible. No one can just come in to visit. Only very important people who have an appointment."

With the chutzpah of the young, I insisted that we would be able to get in and approached the guard with these words: "Would you please call Mr. Hemingway and tell him that three rabbis from New York are here to see him."

How could Hemingway not be intrigued? Surely he would wonder what in the world three rabbis wanted to talk to him about. We held our breaths, and the guard himself could not bElive it when the message came back from the house that Mr. Hemingway would see us.

We were ushered into Hemingway's presence as he sat in his spacious den. What followed, we subsequently learnt, was a verbal volley meant to establish whether it was worthwhile for him to spend any time talking to us. He questioned us about our backgrounds, threw some literary allusions at us to see if we would understand their meaning, asked what we thought was the symbolic meaning of some passages in his A Farewell To Arms—and then after about 15 minutes totally changed his demeanor and spoke to us with a great deal of warmth and friendship.

"Rabbis," he said to us, "forgive me for having been brusque with you at first but before continuing I had to make certain it was worth my while to talk to you. To be honest, I've long wanted to engage a rabbi in conversation. I just never had the opportunity. And now suddenly out of the blue you've come to me."

Hemingway then opened up to us in most remarkable manner. He told us he had a great interest in religion for many years which he pursued privately and never discussed or wrote about. He said during one period of his life he set aside time to study many of the major religions in depth.

He said that after he thought deeply about the different religions he studied, he came to an important conclusion. Fundamentally he realized all religions divide into one of two major categories. There are religions of death and there are religions of life. Religions of death are the ones whose primary emphasis is preparation for an afterlife. This world and its pleasures are renounced in favor of dedicating oneself totally to the world to come. "Obviously," he added, "that isn't for me." What he respects, he continued, is the religion of Judaism which stress our obligations to what we are here for now on earth rather than the hereafter.

With his perceptive mind, he summed up the essence of Judaism perhaps better than most Jews themselves can. Judaism is a religion of life. "Choose life," says the Torah.

Rabbi Bleich continues:

I took the opportunity to compliment Hemingway on his analysis and had the temerity to ask if I might teach him something that would add to his insight. I told him of the biblical law that prohibits the Kohanim, all the members of the Jewish priesthood, from coming into any contact with the dead. If they did so, they would be considered impure. To this day Kohanim cannot enter a funeral chapel with a body inside.

The rabbinic commentators questioned the reason behind this law. The answer that resonates most with scholars is that the Torah wanted to ensure that the priestly class, those assigned to dedicate themselves to the spiritual needs of their people, did not misconstrue their primary function. In all too many religions, the holy men devote themselves almost exclusively to matters revolving around death. Even in our own times, the only connection many people have with a spiritual leader is at a funeral. That is why the Bible forbade the priests from having any contact with the dead—so that they spend their time, their efforts, their concerns and their energy with the living.

Hemingway smiled and thanked me for sharing with him this beautiful idea.

This encounter with Hemingway became all the more poignant when, in just a few years, on July 2, 1961, the man whose hand wrote the books we revere to this day chose to use it to put the barrel of his shotgun into his mouth and commit suicide. Somehow, Hemingway was never able to find a spiritual source on which to lean in order to give him a reason for living. He had taught the world, in his words, "But man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated." And yet, tragically, the biblical ideal to "choose life" that he praised in our meeting could not guide him in the end.

The Watch

But let me tell you know a very different story, about another great author and a great Jew, Holocaust survivor and witness, Eli Wiesel, who died three months ago, in July 2016, at the age of 87.

“The Watch” is the name of an autobiographical tale told by Eli Wiesel in his 1965 book, One Generation After. Wiesel shares the story of his first, and what would be his only, return to the town of his birth, Sighet, Rumania, since the conclusion of World War II.

For his bar mitzvah, Wiesel explains, he had received a beautiful gold watch, a gift he treasured dearly until a few years later when he had turned fifteen, and the Nazis came, followed by the edicts, and then the ghettos, the transports, and eventually the fateful hours just before Passover of 1944 when the 10,000 Jews of Sighet were sent to their death. As the roundups began, but with the darkness of the night yet to come still beyond their sight, Eli and his family began to dig feverishly into the ground in order to bury the jewelry, the candelabras, the family heirlooms – anything and everything of value – in the naive hope that one day they would return to retrieve them. Eli had one and only one possession of value – his bar mitzvah watch – and so like the rest his family, he decided to bury it, three steps from the fence, beneath the poplar tree, to be recovered one day.

And so two days before Passover in 1944, on the night before he and his family were deported to Auschwitz, 15-year-old Eli Wiesel dug a hole in the garden of his home and buried a gold watch his beloved grandfather had given him.

Twenty years and an eternity later, Wiesel returns unannounced to Sighet with the mission of retrieving his cherished watch. It is the middle of the night as Eli secretly and cautiously sneaks into the yard of his childhood, careful not to wake the family sleeping in the home that was once his. He retraces his steps to the exact location, and using his bare hands, begins to scratch and dig into the frozen ground as minutes, or maybe it was hours, pass. Suddenly his fingers hit something hard and metallic and he exhumes the box containing the relic from his past, the only remaining symbol of all that had been—and went up in flames. The intervening years had not been kind to the watch: it was rusty and covered with dirt. Eli nonetheless touches it, caresses it, and raises it lovingly to his lips. At that moment Wiesel resolves to bring it to the best jeweler in the world to recover the luster it once had.

He want to take with him this one last item of his innocent youth—before it was all destroyed.

Sensing the rising of the sun and coming of dawn, Wiesel hurriedly stuffs the watch into his pocket and runs out of the garden and courtyard. He does not want to be caught. He is halfway down the street when – inexplicably – he stops dead in his tracks. He does an about face, retraces his steps to that poplar tree in the garden, and in his words, “as at Yom Kippur services,” kneels down, places the watch back into the box, the box back into the hole, and then proceeds to once more fill up the hole with earth.

The story ends with Wiesel wondering to himself why he did what he did. Walking away, he imagines hearing the voices of his childhood village along with the tick-tock of the just buried watch. Leaving his village never to return, Wiesel concludes: “Since that day, the town of my childhood has ceased being just another town. It has become the face of the watch.”[2]

Eli Wiesel, as is his nature, leaves the rest of the story to our imagination. And in my imagination, this little story captures the distinction between Hemingway and Wiesel—where one man haunted by the horrors of his past, who lost much his family to the Germans, went on to inspire people to live and love, and the other felt compelled to put an end to his tortured and deep soul.

It also captures the essence of Yizkor.

The Soul Needs You

Judaism believes in afterlife, as does most every religion in the world. A soul never dies; it lives for eternity. Our life here on earth is but a small part of our soul’s journey. The soul, by its very nature, is not physical, it is not made up of physical stuff, and no physical ailment and death can obliterate it.

And yet, Judaism teaches that the most important experience of the soul is the time it spends down here in this world. For the ultimate purpose of creation was not heaven, but earth. G-d wants humanity to build a fragment of heaven on earth, to create a world of goodness and holiness.

Hemingway put it so well, that Judaism is a “religion of life.” But it goes even deeper than he imagined. Even after the soul leaves us, it never disconnects from us. Not only is the soul eternally alive, but the soul is also eternally connected to its loved ones here on earth. The soul craves that its ideals, dreams, aspirations and good deeds should be continued here on earth, because the soul knows that the objective of all of creation was to transform our world into a

Divine abode. So as high up as the soul goes, it never stops to look down and see how we are continuing its life. The soul craves to continue living here through us—through our lives and deeds! What I do down here in my life on earth impact profoundly the soul of my loved one, though I can’t see him, hear him, touch him, feel him or kiss him, or her. When I give charity down here in this world, I create an impact not only for the person I gave the charity for, but also for the soul of my loved ones who may be gone for decades.

A man once shared this:

“I lost my son, and since his death just could not go on. I hoped that time would heal, but everyday was just as the day of the funeral. I searched amongst the wise and saintly leaders for comfort and direction but found none. Tonight, I have come to the Lubavitcher Rebbe for guidance and comfort. The Rebbe said to me as follows, ‘If your son was well but taken away that you could not see him, would you be able to live with that?’ To which I responded, definitely, it would be painful, however, it would be livable.’ The Rebbe then continued, “and if you were told that you may send your son care-packages and be guaranteed that he would receive them and that they would be of good use, would you send packages?’ ‘Why, of course,’ I replied. The Rebbe than looked me deep in my eyes and said, ‘I assure you that your son is okay in Heaven, and I assure you that your care-packages will reach him and be of good use. Send him a Kaddish, Mishnayos, and charity.’”

“For the first time since the death of my son, some despair was lifted from my heart,” concluded the man. “Yes, it is very painful that I cannot physically see him, hear him, and hug him, but I know now that he is okay, and a new form of communication can exist.”

So G-d remember each end every soul, even without our saying yizkor and asking Him not to forget. A mother does not forget her child and G-d forgets no soul. When we ask G-d to remember the soul of our loved ones it is like the Torah says, “G-d remembered Rachel,” or when G-d says, “I remember the Jews in Egypt,” or, “I will remember the covenant with Jacob.” It is not that He forgot it and He now reminds Himself. It means that He will tune-in tad respond to the particular needs of this soul, to grant the soul all it needs, including what the souk asks for in terms of its loved ones.

This is the reason we say in Yizkor, “Remember my father or my mother because I will be giving charity in their merit.” By me giving charity for their sake, I am allowing their soul to be empowered, invigorated, inspired, elevated and nurtured. My mitzvah, my tzedakah, that I do for the soul, has such a powerful impact, that G-d Himself “remembers” and responds to every single needs of this soul.

There is nothing that has such a positive impact on the soul like the good deeds we do down here. For this is the space where all actions happens.

Thus, we remember our loved ones not only by missing them, crying for them, and yearning for them. Of course, that is natural. But the deepest and most authentic way of remembering them is by being here for them, by showing up for them. And how can we be here for them? By doing things that they would have done had they been living; and now they need us to do it. And when we do it—it brings them infinite joy and helps them in infinite ways.

This is one of the great ideas in the Jewish religion[3]—the ultimate “religion of life,” that the small, concrete deeds of a person living here on earth creates a powerful impact on a neshamah, a soul, that is not only 40,000 miles above earth, but in a completely different zone, so to speak. Our acts of charity, or learning Torah, or prayer, or other mitzvos, causes G-d himself to connect to that particular soul in a unique and special way and fulfill its needs and wants.

I think this is what Eli Wiesel felt when he returned the watch to the hole in the earth. He felt that the watch, and all it represented, belonged to a past world, and he did not want to take it along with him. You must remember my past, but you can’t take it along wherever you go, because then you may remain stuck in your past. And the main calling of your past must be to continue living. What our loved ones want most is that we continue moving, living and growing. If we just yearn for the past, we compromise not only our happiness, but also their happiness.

A Journey From Iran

In her introduction to her book “Life is a Gift,” Dr. Miriam Adahan, a therapist and author, relates that when she moved to Israel from the US, in 1981, they lived for a while in an absorption center. There, she writes, I became friendly with a young widow with four children who had come from Iran a year and a half before in 1979. Although she lived in a tiny, one room apartment and worked as a clerk in the local post office, she had this regal dignity which hinted at a refined background.

As our eleven-year-old daughters became best friends, the story of her previous life had emerged.

In Iran, they had been very wealthy, with servants, beautiful cars and expensive vacations abroad. Then came the overthrow of the Shah in 1979 by the Aytalah Chuemeni, and the reign of terror against the Jews began. One day, a gang of thugs entered her husband's rug store and shot him dead, they defaced the walls with his blood, proclaiming him an agent of the Shah.

Informed of the awful tragedy, the grief stricken widow knew she had to leave Iran immediately to save herself and her children.

Desperately trying to stay in control she contacted a man who was known to be helping Jews escape over the treacherous mountains through Turkey.

Since unauthorized travel was forbidden and the sale of any household items might arouse suspicions she had to leave most of her wealth behind. She could not tell anyone of her plans, not even her children. She could not pack suitcases, as neighbors might see and report her to the police.

Trembling, and trying not to let her terror show, she took whatever little cash and jewelry she had on hand, and telling her children that they were going shopping, left the home, never to return.

In the darkness of night, they met their guide at the edge of Teheran. Handing over most of her money and jewelry, the harrowing nightmare began for this brave widow and her four children, and the youngest a girl of three.

For The first few days, they spent eighteen hours at a time on camels. The pain they suffered was so excruciating that they often felt they would collapse.

The mother sustained permanent damage to her back. But each time they complained, the guide yelled, took out his revolver and said that he would shoot them if they said another word.

They had no choice but to go on.

By day, the sun scorched them, at night, they froze. As the mountains got steeper, they switched to riding donkeys. Often, the road was so narrow that one wrong move and the donkey and its rider would plunge to the abyss below. The mother said, we cannot continue… we are going back…but the guide yelled, took out his revolver and threatened to shoot them if they said another word….there is no going back he said.

Once, in their rush to cross a freezing stream, they all lost their shoes in the mucky water. When they reached the other side they had to walk barefooted on prickly cactus plants and sharp stones.

Wincing in pain, as the thorns and pebbles cut into their flash. With pain and fatigue, the mother and her older son took turns carrying the youngest child.

At another point they had to make their way across a flimsy bridge made of ropes and wooden slats which stretched between two mountain peaks and spanned and deep ravine. The ropes looked as though they could barely hold their own weight, let alone a group of terrified Jewish refugees. Looking down into the abyss below, the mother froze into utter terror, crying out that she could not possibly go on.

Again, their guide took out his gun and threatened her and her children with death if they did not move. Taking her three year old by the hand, she forced herself to grab the ropes, fueled by anger towards the Iranian guide who urged them on so gruffly.

After two-and-a-half weeks of this continuous torture, the small group of Jewish refugees arrived at the Turkish border. There, the guide, who had always been so harsh, so cruel and unsympathetic- suddenly embraced each child warmly and said to the mother:

"Before I leave you, I want to tell you that I, too, am Jewish. I'm sorry I had to be so rough. But if I had been nice to you, you wouldn't have made it. I had to scare you, I had to threaten you, I had to intimidate you into moving, or you would not have been able to go on."

And with tears in his eyes he said, "I’m so proud of each and every one of you. You are all true gibborim—heroes to have made it to this point of freedom." With that, he turned and left to go back in the direction of Iran, while this family eventually made it to Israel and started a new life.

Continue the Journey

After reading this story, I thought to myself, that like this heroic family, we, too, are on a journey which is often treacherous and filled with challenges and pain. As we say yizkor, we recall in sadness and fondness those who left us and here with us anymore. It’s painful, it’s sad, especially for the young members of our families who will never know these people.

And yet, as yizkor reminds us, our main duty to our loved ones is to continue the journey here on earth and not to stop moving. And one thing we know for sure: Our guide always loves us, even when He challenges us, and that all the difficulties we go through must empower us to continue our journey and mission.

Hemingway said: The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places. Sadly, he could not find that strength in the broken places. Yet the “religion of life” beacons us to remember the awesome power that lay in our living a life here on earth saturated with Torah and Mitzvos and good deeds, one that even souls gone for millennia look towards in order to be uplifted and elevated.[4]

[2] One Generation After, pp. 60–65

[3] This was a unique expression the Rebbe used in his talk on 20 Av, 5729 (1969). It was a rare expression: “This seems to be one of great novel ideas of the Jewish religion and the Jewish faith that we can impact a soul above.”

[4] This sermon is based on Sichas 20 Av 5729; Sichas Shabbos Yisro 22 shevat 5749.

Categories

Shemini Atzeres/Simchas Torah 5777

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 16, 2016

- |

- 14 Tishrei 5777

- |

- 30 views

Choose Life: Hemingway, Wiesel & Yizkor

”Remember the Soul of My Parents Because I will Donate to Charity”

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 16, 2016

Make Sure He's Dead

A couple of Montana hunters are out in the woods when one of them falls to the ground. He doesn't seem to be breathing, his eyes are rolled back in his head. The other guy whips out his cell phone and calls the emergency services. He gasps to the operator: “My friend is dead! What can I do?”

The operator, in a calm soothing voice says: “Just take it easy. I can help. First, let's make sure he's dead.” There is a silence, then a shot is heard.

The guy's voice comes back on the line. He says: “OK, now what?“

The Storm

Sadie has died and today is her funeral. Her husband Nathan and many of

their family and friends are standing round the grave as Sadie's coffin is

lowered into the ground. Then, as is the custom, many of the mourners pick

up some shovels and help to fill the open grave with earth.

But on their way back to the prayer hall, the sky suddenly darkens, rain

starts to fall, flashes of lightening fill the sky and loud thunder rings

out.Nathan turns to his rabbi and says, "Well rabbi, she's arrived alright."

Strange Text of Yizkor

Yizkor, a special memorial prayer for the departed, is recited in the synagogue four times a year, following the Torah reading on the last day of Passover, on the second day of Shavuot, on Yom Kippur, and today—on Shemini Atzeres.

Yizkor, in Hebrew, means "Remember." It is not only the first word of the prayer, it also represents its overall theme. In this prayer, we implore G‑d to remember the souls of our relatives and friends that have passed on.

This is the text of Yizkor: “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher (and we mention his or her Hebrew name and that of his or her mother)—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—who has gone to his [supernal] world, because I will (without obligating myself with a vow) donate charity for his/her sake. In this merit, may his soul be bound up in the bond of life with the souls of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, and with the other righteous men and women who are in Gan Eden; and let us say, Amen.

There are two strange things here. First, why are we asking G-d to “remember” the soul of our father, mother, or other loved ones, when we know He remembers everything? As we say on Rosh Hashanah, “There is no forgetfulness before the throne of Your Glory.” If we cannot forget the soul of someone we have lost, how could G-d forget him or her? After all, G-d created that soul, for sure He does not forget it!

In the stirring words of Isaiah:

The second enigma is the reason we give to G-d for remembering the soul. “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—because I will donate charity for his/her sake.” Really? G-d should remember them because I will give a check to charity? If I don’t give 18 dollars or 1800 dollars to charity G-d might forget them; but since I am giving some charity, therefore G-d shall remember them?

In truth, one question is answered by the other.

Hemingway and Bleich

I want to share with you a fascinating story about a meeting between a young American Rabbi, and arguably the greatest writer of the 20th century.

One of the greatest authors in American history, whose works are considered timeless classics of American literature, was Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961). Rabbi Benjamin Blech, who serves today a professor at Yeshiva University in NY, related the following personal episode.[1]

The year was 1956. I had just been ordained and felt I needed a vacation after completing years of rigorous study, to get ordained by the famed Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik. Together with two other newly minted rabbis, we decided on a trip that in those days was considered rather exotic. We chose pre-Castro Cuba as our destination—not too far away, not too costly, beautiful and totally different from our New York City environment.

One day as we drove through Havana and its outskirts, our combination taxi driver/guide pointed out a magnificent estate and told us that this was the residence of the writer, Ernest Hemingway. "Stop the car," we told him. "We want to go in." He shook his head and vehemently told us, "No, no, that is impossible. No one can just come in to visit. Only very important people who have an appointment."

With the chutzpah of the young, I insisted that we would be able to get in and approached the guard with these words: "Would you please call Mr. Hemingway and tell him that three rabbis from New York are here to see him."

How could Hemingway not be intrigued? Surely he would wonder what in the world three rabbis wanted to talk to him about. We held our breaths, and the guard himself could not bElive it when the message came back from the house that Mr. Hemingway would see us.

We were ushered into Hemingway's presence as he sat in his spacious den. What followed, we subsequently learnt, was a verbal volley meant to establish whether it was worthwhile for him to spend any time talking to us. He questioned us about our backgrounds, threw some literary allusions at us to see if we would understand their meaning, asked what we thought was the symbolic meaning of some passages in his A Farewell To Arms—and then after about 15 minutes totally changed his demeanor and spoke to us with a great deal of warmth and friendship.

"Rabbis," he said to us, "forgive me for having been brusque with you at first but before continuing I had to make certain it was worth my while to talk to you. To be honest, I've long wanted to engage a rabbi in conversation. I just never had the opportunity. And now suddenly out of the blue you've come to me."

Hemingway then opened up to us in most remarkable manner. He told us he had a great interest in religion for many years which he pursued privately and never discussed or wrote about. He said during one period of his life he set aside time to study many of the major religions in depth.

He said that after he thought deeply about the different religions he studied, he came to an important conclusion. Fundamentally he realized all religions divide into one of two major categories. There are religions of death and there are religions of life. Religions of death are the ones whose primary emphasis is preparation for an afterlife. This world and its pleasures are renounced in favor of dedicating oneself totally to the world to come. "Obviously," he added, "that isn't for me." What he respects, he continued, is the religion of Judaism which stress our obligations to what we are here for now on earth rather than the hereafter.

With his perceptive mind, he summed up the essence of Judaism perhaps better than most Jews themselves can. Judaism is a religion of life. "Choose life," says the Torah.

Rabbi Bleich continues:

I took the opportunity to compliment Hemingway on his analysis and had the temerity to ask if I might teach him something that would add to his insight. I told him of the biblical law that prohibits the Kohanim, all the members of the Jewish priesthood, from coming into any contact with the dead. If they did so, they would be considered impure. To this day Kohanim cannot enter a funeral chapel with a body inside.

The rabbinic commentators questioned the reason behind this law. The answer that resonates most with scholars is that the Torah wanted to ensure that the priestly class, those assigned to dedicate themselves to the spiritual needs of their people, did not misconstrue their primary function. In all too many religions, the holy men devote themselves almost exclusively to matters revolving around death. Even in our own times, the only connection many people have with a spiritual leader is at a funeral. That is why the Bible forbade the priests from having any contact with the dead—so that they spend their time, their efforts, their concerns and their energy with the living.

Hemingway smiled and thanked me for sharing with him this beautiful idea.

This encounter with Hemingway became all the more poignant when, in just a few years, on July 2, 1961, the man whose hand wrote the books we revere to this day chose to use it to put the barrel of his shotgun into his mouth and commit suicide. Somehow, Hemingway was never able to find a spiritual source on which to lean in order to give him a reason for living. He had taught the world, in his words, "But man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated." And yet, tragically, the biblical ideal to "choose life" that he praised in our meeting could not guide him in the end.

The Watch

But let me tell you know a very different story, about another great author and a great Jew, Holocaust survivor and witness, Eli Wiesel, who died three months ago, in July 2016, at the age of 87.

“The Watch” is the name of an autobiographical tale told by Eli Wiesel in his 1965 book, One Generation After. Wiesel shares the story of his first, and what would be his only, return to the town of his birth, Sighet, Rumania, since the conclusion of World War II.

For his bar mitzvah, Wiesel explains, he had received a beautiful gold watch, a gift he treasured dearly until a few years later when he had turned fifteen, and the Nazis came, followed by the edicts, and then the ghettos, the transports, and eventually the fateful hours just before Passover of 1944 when the 10,000 Jews of Sighet were sent to their death. As the roundups began, but with the darkness of the night yet to come still beyond their sight, Eli and his family began to dig feverishly into the ground in order to bury the jewelry, the candelabras, the family heirlooms – anything and everything of value – in the naive hope that one day they would return to retrieve them. Eli had one and only one possession of value – his bar mitzvah watch – and so like the rest his family, he decided to bury it, three steps from the fence, beneath the poplar tree, to be recovered one day.

And so two days before Passover in 1944, on the night before he and his family were deported to Auschwitz, 15-year-old Eli Wiesel dug a hole in the garden of his home and buried a gold watch his beloved grandfather had given him.

Twenty years and an eternity later, Wiesel returns unannounced to Sighet with the mission of retrieving his cherished watch. It is the middle of the night as Eli secretly and cautiously sneaks into the yard of his childhood, careful not to wake the family sleeping in the home that was once his. He retraces his steps to the exact location, and using his bare hands, begins to scratch and dig into the frozen ground as minutes, or maybe it was hours, pass. Suddenly his fingers hit something hard and metallic and he exhumes the box containing the relic from his past, the only remaining symbol of all that had been—and went up in flames. The intervening years had not been kind to the watch: it was rusty and covered with dirt. Eli nonetheless touches it, caresses it, and raises it lovingly to his lips. At that moment Wiesel resolves to bring it to the best jeweler in the world to recover the luster it once had.

He want to take with him this one last item of his innocent youth—before it was all destroyed.

Sensing the rising of the sun and coming of dawn, Wiesel hurriedly stuffs the watch into his pocket and runs out of the garden and courtyard. He does not want to be caught. He is halfway down the street when – inexplicably – he stops dead in his tracks. He does an about face, retraces his steps to that poplar tree in the garden, and in his words, “as at Yom Kippur services,” kneels down, places the watch back into the box, the box back into the hole, and then proceeds to once more fill up the hole with earth.

The story ends with Wiesel wondering to himself why he did what he did. Walking away, he imagines hearing the voices of his childhood village along with the tick-tock of the just buried watch. Leaving his village never to return, Wiesel concludes: “Since that day, the town of my childhood has ceased being just another town. It has become the face of the watch.”[2]

Eli Wiesel, as is his nature, leaves the rest of the story to our imagination. And in my imagination, this little story captures the distinction between Hemingway and Wiesel—where one man haunted by the horrors of his past, who lost much his family to the Germans, went on to inspire people to live and love, and the other felt compelled to put an end to his tortured and deep soul.

It also captures the essence of Yizkor.

The Soul Needs You

Judaism believes in afterlife, as does most every religion in the world. A soul never dies; it lives for eternity. Our life here on earth is but a small part of our soul’s journey. The soul, by its very nature, is not physical, it is not made up of physical stuff, and no physical ailment and death can obliterate it.

And yet, Judaism teaches that the most important experience of the soul is the time it spends down here in this world. For the ultimate purpose of creation was not heaven, but earth. G-d wants humanity to build a fragment of heaven on earth, to create a world of goodness and holiness.

Hemingway put it so well, that Judaism is a “religion of life.” But it goes even deeper than he imagined. Even after the soul leaves us, it never disconnects from us. Not only is the soul eternally alive, but the soul is also eternally connected to its loved ones here on earth. The soul craves that its ideals, dreams, aspirations and good deeds should be continued here on earth, because the soul knows that the objective of all of creation was to transform our world into a

Divine abode. So as high up as the soul goes, it never stops to look down and see how we are continuing its life. The soul craves to continue living here through us—through our lives and deeds! What I do down here in my life on earth impact profoundly the soul of my loved one, though I can’t see him, hear him, touch him, feel him or kiss him, or her. When I give charity down here in this world, I create an impact not only for the person I gave the charity for, but also for the soul of my loved ones who may be gone for decades.A man once shared this:

“I lost my son, and since his death just could not go on. I hoped that time would heal, but everyday was just as the day of the funeral. I searched amongst the wise and saintly leaders for comfort and direction but found none. Tonight, I have come to the Lubavitcher Rebbe for guidance and comfort. The Rebbe said to me as follows, ‘If your son was well but taken away that you could not see him, would you be able to live with that?’ To which I responded, definitely, it would be painful, however, it would be livable.’ The Rebbe then continued, “and if you were told that you may send your son care-packages and be guaranteed that he would receive them and that they would be of good use, would you send packages?’ ‘Why, of course,’ I replied. The Rebbe than looked me deep in my eyes and said, ‘I assure you that your son is okay in Heaven, and I assure you that your care-packages will reach him and be of good use. Send him a Kaddish, Mishnayos, and charity.’”

“For the first time since the death of my son, some despair was lifted from my heart,” concluded the man. “Yes, it is very painful that I cannot physically see him, hear him, and hug him, but I know now that he is okay, and a new form of communication can exist.”

So G-d remember each end every soul, even without our saying yizkor and asking Him not to forget. A mother does not forget her child and G-d forgets no soul. When we ask G-d to remember the soul of our loved ones it is like the Torah says, “G-d remembered Rachel,” or when G-d says, “I remember the Jews in Egypt,” or, “I will remember the covenant with Jacob.” It is not that He forgot it and He now reminds Himself. It means that He will tune-in tad respond to the particular needs of this soul, to grant the soul all it needs, including what the souk asks for in terms of its loved ones.

This is the reason we say in Yizkor, “Remember my father or my mother because I will be giving charity in their merit.” By me giving charity for their sake, I am allowing their soul to be empowered, invigorated, inspired, elevated and nurtured. My mitzvah, my tzedakah, that I do for the soul, has such a powerful impact, that G-d Himself “remembers” and responds to every single needs of this soul.

There is nothing that has such a positive impact on the soul like the good deeds we do down here. For this is the space where all actions happens.

Thus, we remember our loved ones not only by missing them, crying for them, and yearning for them. Of course, that is natural. But the deepest and most authentic way of remembering them is by being here for them, by showing up for them. And how can we be here for them? By doing things that they would have done had they been living; and now they need us to do it. And when we do it—it brings them infinite joy and helps them in infinite ways.

This is one of the great ideas in the Jewish religion[3]—the ultimate “religion of life,” that the small, concrete deeds of a person living here on earth creates a powerful impact on a neshamah, a soul, that is not only 40,000 miles above earth, but in a completely different zone, so to speak. Our acts of charity, or learning Torah, or prayer, or other mitzvos, causes G-d himself to connect to that particular soul in a unique and special way and fulfill its needs and wants.

I think this is what Eli Wiesel felt when he returned the watch to the hole in the earth. He felt that the watch, and all it represented, belonged to a past world, and he did not want to take it along with him. You must remember my past, but you can’t take it along wherever you go, because then you may remain stuck in your past. And the main calling of your past must be to continue living. What our loved ones want most is that we continue moving, living and growing. If we just yearn for the past, we compromise not only our happiness, but also their happiness.

A Journey From Iran

In her introduction to her book “Life is a Gift,” Dr. Miriam Adahan, a therapist and author, relates that when she moved to Israel from the US, in 1981, they lived for a while in an absorption center. There, she writes, I became friendly with a young widow with four children who had come from Iran a year and a half before in 1979. Although she lived in a tiny, one room apartment and worked as a clerk in the local post office, she had this regal dignity which hinted at a refined background.

As our eleven-year-old daughters became best friends, the story of her previous life had emerged.

In Iran, they had been very wealthy, with servants, beautiful cars and expensive vacations abroad. Then came the overthrow of the Shah in 1979 by the Aytalah Chuemeni, and the reign of terror against the Jews began. One day, a gang of thugs entered her husband's rug store and shot him dead, they defaced the walls with his blood, proclaiming him an agent of the Shah.

Informed of the awful tragedy, the grief stricken widow knew she had to leave Iran immediately to save herself and her children.

Desperately trying to stay in control she contacted a man who was known to be helping Jews escape over the treacherous mountains through Turkey.

Since unauthorized travel was forbidden and the sale of any household items might arouse suspicions she had to leave most of her wealth behind. She could not tell anyone of her plans, not even her children. She could not pack suitcases, as neighbors might see and report her to the police.

Trembling, and trying not to let her terror show, she took whatever little cash and jewelry she had on hand, and telling her children that they were going shopping, left the home, never to return.

In the darkness of night, they met their guide at the edge of Teheran. Handing over most of her money and jewelry, the harrowing nightmare began for this brave widow and her four children, and the youngest a girl of three.

For The first few days, they spent eighteen hours at a time on camels. The pain they suffered was so excruciating that they often felt they would collapse.

The mother sustained permanent damage to her back. But each time they complained, the guide yelled, took out his revolver and said that he would shoot them if they said another word.

They had no choice but to go on.

By day, the sun scorched them, at night, they froze. As the mountains got steeper, they switched to riding donkeys. Often, the road was so narrow that one wrong move and the donkey and its rider would plunge to the abyss below. The mother said, we cannot continue… we are going back…but the guide yelled, took out his revolver and threatened to shoot them if they said another word….there is no going back he said.

Once, in their rush to cross a freezing stream, they all lost their shoes in the mucky water. When they reached the other side they had to walk barefooted on prickly cactus plants and sharp stones.

Wincing in pain, as the thorns and pebbles cut into their flash. With pain and fatigue, the mother and her older son took turns carrying the youngest child.

At another point they had to make their way across a flimsy bridge made of ropes and wooden slats which stretched between two mountain peaks and spanned and deep ravine. The ropes looked as though they could barely hold their own weight, let alone a group of terrified Jewish refugees. Looking down into the abyss below, the mother froze into utter terror, crying out that she could not possibly go on.

Again, their guide took out his gun and threatened her and her children with death if they did not move. Taking her three year old by the hand, she forced herself to grab the ropes, fueled by anger towards the Iranian guide who urged them on so gruffly.

After two-and-a-half weeks of this continuous torture, the small group of Jewish refugees arrived at the Turkish border. There, the guide, who had always been so harsh, so cruel and unsympathetic- suddenly embraced each child warmly and said to the mother:

"Before I leave you, I want to tell you that I, too, am Jewish. I'm sorry I had to be so rough. But if I had been nice to you, you wouldn't have made it. I had to scare you, I had to threaten you, I had to intimidate you into moving, or you would not have been able to go on."

And with tears in his eyes he said, "I’m so proud of each and every one of you. You are all true gibborim—heroes to have made it to this point of freedom." With that, he turned and left to go back in the direction of Iran, while this family eventually made it to Israel and started a new life.

Continue the Journey

After reading this story, I thought to myself, that like this heroic family, we, too, are on a journey which is often treacherous and filled with challenges and pain. As we say yizkor, we recall in sadness and fondness those who left us and here with us anymore. It’s painful, it’s sad, especially for the young members of our families who will never know these people.

And yet, as yizkor reminds us, our main duty to our loved ones is to continue the journey here on earth and not to stop moving. And one thing we know for sure: Our guide always loves us, even when He challenges us, and that all the difficulties we go through must empower us to continue our journey and mission.

Hemingway said: The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places. Sadly, he could not find that strength in the broken places. Yet the “religion of life” beacons us to remember the awesome power that lay in our living a life here on earth saturated with Torah and Mitzvos and good deeds, one that even souls gone for millennia look towards in order to be uplifted and elevated.[4]

[2] One Generation After, pp. 60–65

[3] This was a unique expression the Rebbe used in his talk on 20 Av, 5729 (1969). It was a rare expression: “This seems to be one of great novel ideas of the Jewish religion and the Jewish faith that we can impact a soul above.”

[4] This sermon is based on Sichas 20 Av 5729; Sichas Shabbos Yisro 22 shevat 5749.

- Comment

Class Summary:

There are two strange things about the text of Yizkor. Why are we asking G-d to “remember” the soul of our father, mother, or other loved ones, when we know He remembers everything? If we cannot forget the soul of someone we have lost, how could G-d forget him or her?

The second enigma is that we say, “May G‑d remember the soul of my father, my teacher, or my mother my teacher—or whichever loved one we are saying yizkor for—because I will donate charity for his/her sake.” Really? G-d should remember them because I will give a check to charity? If I don’t give 18 dollars or 1800 dollars to charity G-d might forget them; but since I am giving some charity, therefore G-d shall remember them?

For this I will share with you a fascinating story about a meeting between a young American Rabbi, and arguably the greatest writer of the 20th century. Hemingway loved the words the rabbi told him about the value of life, but it could not stop him from taking his own life.

Contrast this with another story about another great author. Two days before Passover in 1944, on the night before he and his family were deported to Auschwitz, 15-year-old Eli Wiesel dug a hole in the garden of his home and buried a gold watch his beloved grandfather had given him for his bar mitzvah.

Twenty years and an eternity later, Wiesel returns unannounced to Sighet with the mission of retrieving his cherished watch. It is the middle of the night as Eli secretly and cautiously sneaks into the yard of his childhood, careful not to wake the family sleeping in the home that was once his. He discovers the watch but then decides to do something very strange with the watch.

The story of a Jewish family that made its way from Iran to Israel in a most treacherous journey, and the advice the Lubavitcher Rebbe gave a bereaved father, captures the primary message of yizkor. The greatest thing I can do for my loved one who is not here any longer is to continue their ideals, dreams and good deeds here on earth.

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!