Yizkor: 3 Principles of Good Living

The Book Vs. the Scroll: The Secret of the Sefer Torah

- October 12, 2011

- |

- 14 Tishrei 5772

Rabbi YY Jacobson

15 views

Yizkor: 3 Principles of Good Living

The Book Vs. the Scroll: The Secret of the Sefer Torah

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 12, 2011

“I’m Not From Here”

You know the story about the rabbi who in the middle of his Yizkor sermon on Yom Kippur, pounds on the table and says ‘Wake up to the fact that every single person in this congregation, myself included, is going to die!”

And as he expected, everyone’s suddenly very alarmed, except for one man in the third row whose face breaks out into a broad smile.

And the rabbi is so shocked, he points to this man and says, “so why are you so amused?”

And the man shrugs his shoulders and answers, “Well I’m not from this congregation. I’m just visiting my sister.”

Don’t Shame Me

A very assimilated Jew who was never in synagogue before came on Yom Kippur to the synagogue for the first time in his life.

Since he did not know what to do, he decided to emulate the person sitting next to him in shul. This way he would be safe and not embarrass himself. When his neighbor stood, he stood; when his neighbor sat, he sat. What the man near him turned a page, he too turned a page, etc.

All went smooth. Till at one point, the stranger to shul saw his neighbor stand up. So he too jumped up from his chair.

His neighbor turned to him and said: “Why are you embarrassing me in public? Sit down at once!”

“How I’m I embarrassing you?” wondered the newcomer. “I have been mimicking you all day long, what’s the problem?”

Don’t you realize? The man said. The Rabbi just announced: “Will the father of the new baby please rise. Well, my wife and I just had a baby a few days ago, so I stood up. Now, to my great disgrace, you stand up too...”

The Scroll

On Simchat Torah, the host of the party (the Baal Simcha), is the Sefer Torah, the Torah Scroll. It is his holiday. We take out the Torah, we dance with it. We become its legs. The greatest honor is to have a chance to hold a Sefer Torah, to hug it, to kiss it, to feel it, to rejoice in the joy of the Torah.

Today I want to talk about the physical anatomy of the Sefer Torah, and how appreciating the characteristics of the physical Sefer Torah will allow us to appreciate the lives and values of our parents and grandparents who we will soon be saying Yizkor for and remembering today.

The Printing Revolution

In an age where even printed newspapers and books are struggling to survive in face of the technological revolution, the information age, the internet, and all of Steve Jobs’ products, the Torah Scroll remains an anomaly. Not only can’t it be used on a Kindle, or on an i-pad, but furthermore, we can’t even read it from a printed book. It must be written on ancient parchment, and then all the parchment pages are sewn together creating the Torah Scroll. Why?

The first printing press was invented by a German Jew, Johannes Gutenberg, around 1450, and it changed civilization. It brought knowledge to the masses, increased literacy and spread information. Interestingly, the first mass-produced book was the Gutenburg Bible. There are 21 complete copies left in existence, and these are widely regarded as the most expensive books in the world, with an estimated price of 35 million dollars (the last time one has been sold was in 1978.)

The printing revolution affected especially the Jewish world. Until the invention of the printing press, Hebrew books were very scarce, as they were produced laboriously by copying from one manuscript to another. Yet unlike the leaders of the Catholic Church, who tried to stop the dissemination of printed books, Rabbinic leaders were highly enthusiastic about the new technology, and considered the craft of printing Avodat ha-Kodesh (holy work). The first Hebrew book was published in Rome in 1470—fourteen years after Gutenberg printed his famous Bible. It was Rashi’s commentary on the Bible. By 1500, eight years after the Jewish expulsion from Spain, 180 Hebrew titles were issued.

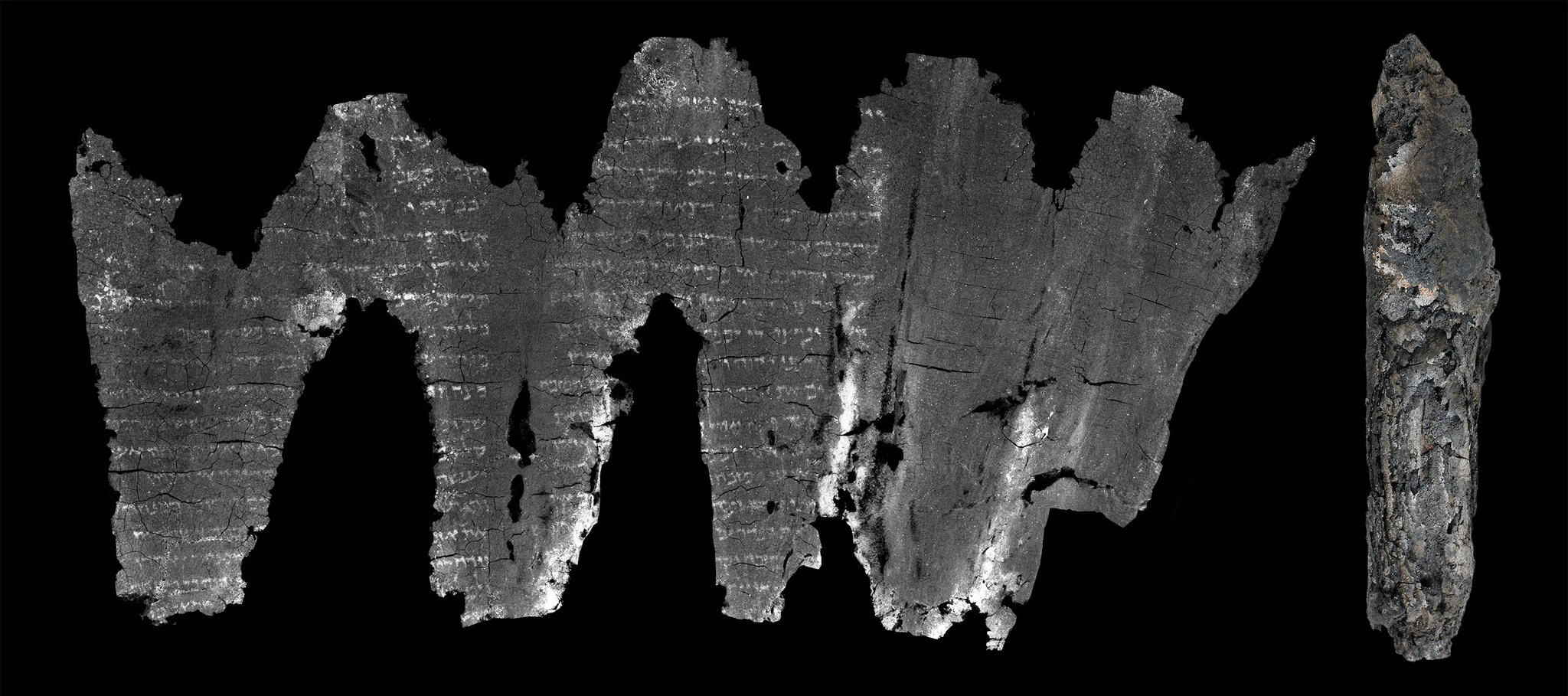

And yet, notwithstanding the blessings of the printing press embraced so enthusiastically by Jews, the Sefer Torah—the Torah Scroll—remains a loner. Till today, 2011, if we want to read form the Torah in the synagogue, it has to be written on a scroll. The Sefer Torah is a living reminder of the way information has been transmitted for four millennia: texts written on scrolls of parchment.

Why the bother of a scribe laboring for more than a year to write the close to 40,000 letters in the Torah with his hand, ink on parchment? This is not only to avoid error. Today with the computer we can produce a perfect error-free Torah scroll in seconds. It is rather to demonstrate the authenticity of the product. Our Torah scroll is an exact copy of a previous one, all the way back to Moses. Moses, in his last days, personally wrote a Torah scroll. If Moses would walk into this synagogue right now and read one of our Torahs, he would discover that letter for letter, word for word, spacing for spacing, this is exactly the same Torah that he personally wrote 3,284 years ago.

But there is something much deeper about the Torah Scroll. There is a lesson in the anatomy of the scroll vs. the book which the Torah wanted us to maintain even in the 21st century.

The History of Mankind Reflected in Books

The Torah states in Genesis, the portion that will be read this coming Shabbos:

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man.

This does not only mean that the Torah records human history; but rather that the very book embodies the history of mankind. If we study the history of the book, we will glean insight into the history of mankind. What is fascinating is that where ancient man is characterized by his scroll, modern man has become like his book.

Three Distinctions

There are three primary differences between the modern book (in print or on Kindle or on the internet) and the ancient scroll.

First of all, in a scroll, when you roll it open, you can already the subsequent pages till the final page, even when you are still holding at the first page. In a book, you can only see each page alone at a time. Only when you conclude one page, can you turn the page, leaving behind that page and exposing what is next.

The second difference is that a scroll is written always only on one side of the parchment, with the flip side remaining blank. A book is always printed on both sides of the page. And on each side there is a different message.

A final major difference is that there is no automatic copying system for scrolls and Sefer Torah’s. Each one must be written painstakingly and individually. Hence, if there is an error that creeps into one scroll, that error might not make it into the second scroll which will be written independently of the first.

Books, on the other hand, are printed using a universal typeset and in an automated system that allows for mass production. If a book has a mistake, then that will mean inevitably that this exact mistake will be found in every other book from this same press.

Ancient Man and Modern Man

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man. The very book embodies the history of mankind.

People used to be like scrolls, but now they are like books—in all three counts.

It used to be that we looked at our lives in a broader perspective, and like a scroll, saw the end initially at the beginning. The human being focused on his or her final destination more than on his present conditions. What was important to man was not the temporary conditions of the here and now, but rather his legacy, his offspring, his family line, how he would be remembered. Man looked a hundred years down the road, or even a thousand years, and made decisions based on what was a priority in a more universal and long-term facts and conditions.

This was not only a Jewish characteristic. Even Laban, the wicked Pagan brother of Rebecca, understood this truth. It is a fascinating and telling moment in Genesis. When Rebecca left to marry Isaac, Laban blessed her as follows: "My sister! May you and your offspring number in the thousands of myriads!" (Genesis 24:60) Laban understood that the future was more important than the present. He did not bless her with wealth, comfort, or a beautiful home, coach and jewelry. Even the scheming Laban saw life from a more global, long term, perspective.

Today we often “behave” like books. We see only as far as the end of the page we are reading, no more. We have become short sighted, not having the courage to attempt to ask the hard questions and provide the tough answers. "How do I want my grandchildren to look?" "How do I want to be remembered? What are the true values that I would have inscribed on my tombstone?" We do no try to picture the end of the story, where the decisions of our youth will take us in life. We seek instant comfort at the expense of long term values. Too many young adults today choose to remain single while enjoying their freedom and independence, and only years later regret the lost opportunity to build families.

You know the anecdote:

Two confirmed bachelors sat talking, their conversation drifted from politics to cooking. "I got a cookbook once," said one, "but I could never do anything with it." "Too much fancy work in it, eh?" asked the other. "You said it. Every one of the recipes began the same way: 'Take a clean dish.’"

Too many couples choose not to have children, or to have only one child, so they can build their careers, but when they grow older, they realize how they erred.

Man today is often unconcerned with the tomorrow, with the future of his life, and works primarily for the comfort of the present. Our parents and grandparents had the strength and stamina to disregard even the tough conditions of the present for the sake of investing in the long-term benefits of the future.

A Son’s Eulogy

A rabbi recently shared an experience he had at a funeral which he officiated at.

The eulogy was delivered by the deceased’s son. From his words we understood that their relationship had its problems. But then tears rolled down his cheeks as he spoke of his father’s patience and love and trust, and asked for forgiveness. He then said, “Dad, I hope it’s not too late to tell you these words that I always felt about you but never told you in person.”

And in a very soft, delicate voice, choking with emotion, he recited the words from the Bette Midler song, “Wind Beneath My Wings:” “Did you ever know that you’re my hero? And everything I’d like to be… that I can fly higher than an eagle, but you are the wind beneath my wings. It might have appeared to go unnoticed, but I got it all here in my heart… thank you, thank you, thank G-d for you, the wind beneath my wings.”

There was not a dry eye in the crowd. Here was a son whose relationship with his father was complicated. He had to wait till the funeral to tell this to his dad. Those words touched all those who were present, reminding them of the significant role that parents play in the lives of their children and how oftentimes it goes unexpressed and seemingly unappreciated until it’s too late.

As we remember today our loved ones who passed, we have to ask ourselves: What are the memories we are creating for our children? Will I spend my life arguing and fighting with my kids because of short-term disagreements? Or will I see the bigger picture, and embrace my children with endless and eternal love that they can then transfer to further generations? Will I be a book or will I be a scroll?

Fakeness

The second difference between a scroll and a book is if it is on one side or two sides. Like a one-sided scroll, people used to be one sided, meaning, honest, straight-forward and direct; they did not have two different messages on the two sides of their life’s page. What you saw is what you got. People were outspoken and blunt, in a refreshing way. Today we are often double-sided like the pages of books. And on every side there is a different message. If you look at me from one side you will see one thing; if you look at me from another side, you will see something very different.

Individuality

Finally, in the earlier generations each scroll was written by a special scribe and each scroll was an original piece of artwork. People were individuals, characters, each paving his or her own way in life. People were original, each one an innovation.

Today, thousands of books are printed as one, giving all of them a single face. Today, we all mimic each other; we all speak, act and look alike. We conform, and do not have the courage to be different. We copy each others virtues and vices, because there is safety in numbers, and this is the way we avoid accountability.

Cherish the Scroll

This is why a Sefer Torah, or a Megillah, in order to be read in the Synagogue, have to be written on scrolls, and are invalid if printed in a book. Notwithstanding the virtues of the printing press, we don’t want to become books, but we want to remain also “scrolls.” And this is what the Torah, and the Torah scroll, tried to teach us,

A Jew who lives life based on Torah, lives with values of the future, of the long-term. He or she thinks of the tomorrow, and not only the tomorrow of this world, but also of the next. Are you living a life that you will be proud of after your passing? Are you nurturing your soul, or only your body? The body will die, but the soul is eternal. What are you doing for your soul?

Torah does not allow man to forget about future, about the bigger picture, about the great family values, about the soul, about the Judaism of our grandchildren.

In addition, Torah despises fakeness. Torah demands integrity of the highest order. Finally, the Torah cherishes true individuality. And it gives a person the courage to maintain stand up to the society around him, and not to bend to peer pressure. A person must be loyal to his own soul, to his heart, and to his own G-d.

As we remember our loved ones during Yizkor, we need to ask ourselves this question: Have I become a book, or I’m I still a scroll, serving as the “feet” to the Torah Scroll I will hold and dance? I’m I thinking about the bigger picture of life? I’m I a real person, living with true honesty and integrity? And finally, I’m I living a life true to my individual and unique potential? I’m I fulfilling the mission for which I was created?

***

Appendix: The Parents Cheering

Rabbi Sholom Moshe Paltiel (Port Washington, NY) shared the following story:

I was visiting Jewish patients in S. Francis Hospital some months back, when I walked into the room of an elderly Jew named Irving, a holocaust survivor, who was obviously quite sick, surrounded by his entire family. I spent some time with him. We talked about the horrors of his youth, and how he managed to continue on living. He told me it was his mother's words to him on the last night before we were separated. "She sat me down and said to me: Life is like a play. (My mother loved the theater). Every one of us plays a part. Not just us, but our parents and grandparents, they're parents and grandparents, all the way back to Abraham and Sarah. They're all part of this production. Each of us plays a part, And then, when your part is over, you go backstage. You're not gone, you're still there, looking, cheering, helping out in any way you can from behind the scenes."

And then mama grabbed my hand, looked me in the eye, and said: "Yisrolik, I don't know what's going to happen, how long we'll be together, whether I'll survive this. But one thing I ask of you, If you survive. Don't give up, play your part. You might feel sad and lonely, but I beg of you- don't give up. Play your role as best you can. Live your life to the fullest. I promise you, you won't be alone. Tate un ich, babe un zeide, mir velen aleh zein mit dir oif eibig, Daddy and me, grandma and grandpa, we will be with you forever, we'll be watching you from backstage. I'm sure you won't let us down and you'll play your part." It was those words from Mama that got me out of bed on many a difficult morning.

By the time the man finished the story, there wasn't a dry eye in the room.

A few days later the man passed away. At the shiva, the family kept repeating the story about the play. It was clear they took comfort from knowing their father was still there, behind the scenes. Still, there was a profound sense of pain and loss.

They asked me to say a few words. So I got up, turned to the family, and I said: There is a postscript to the story. What happens at the end of the play? All the actors comes back out. Right? Everyone comes out on the stage to give a bow. It is a basic Jewish belief that all the neshomos, every soul will come back and be with us once again, right here in this world. I assure you, I said, with G-d's help, you will soon be reunited with your father."

My dear beloved friends, my fellow yiden, we're about to say the Yiskor prayer. Remembering our loved ones whose souls join us right here in shul. Let's promise to make them proud. Let's make this the year when each of us reaches our potential, when each of us lives each day to the fullest, When we realize the beauty of every moment. when we appreciate the G-dly purpose we have been privileged to be a part of.

And while we're at it, let's ask our loved one's to send an email or put in a phone call to the producer, Or maybe even pay Him a visit. Tell Him, please. We're ready for Moshiach. We've done our job. Enough with the yiddishe tzoros, shoin tzeit, it's time already. We're ready for the time when, as we say in the Alanu prayer, “lecho tichra kol berech,” all creations will bow to you. We're ready for the final bow.

- Comment

Class Summary:

In an age where even printed newspapers and books are struggling to survive in face of the technological revolution, the information age, the internet, and all of Steve Jobs’ products, the Torah Scroll remains an anomaly. Not only can’t it be used on a Kindle, or on an i-pad, but furthermore, we can’t even read it from a printed book. It must be written on ancient parchment, and then all the parchment pages are sewn together creating the Torah Scroll. Why?

The 15th century saw the revolution of the printing press which changed civilization. Yet Judaism demands that the Torah still be written as an ancient scroll, because the three distinctions between a scroll and a book embody the three major distinctions between ancient and modern man.

As we remember our loved ones during Yizkor, we need to ask ourselves this question: Have I become a book, or I’m I still a scroll, serving as the “feet” to the Torah Scroll I will hold and dance? I’m I thinking about the bigger picture of life? I’m I a real person, living with true honesty and integrity? And finally, I’m I living a life true to my individual and unique potential? I’m I fulfilling the mission for which I was created?

“I’m Not From Here”

You know the story about the rabbi who in the middle of his Yizkor sermon on Yom Kippur, pounds on the table and says ‘Wake up to the fact that every single person in this congregation, myself included, is going to die!”

And as he expected, everyone’s suddenly very alarmed, except for one man in the third row whose face breaks out into a broad smile.

And the rabbi is so shocked, he points to this man and says, “so why are you so amused?”

And the man shrugs his shoulders and answers, “Well I’m not from this congregation. I’m just visiting my sister.”

Don’t Shame Me

A very assimilated Jew who was never in synagogue before came on Yom Kippur to the synagogue for the first time in his life.

Since he did not know what to do, he decided to emulate the person sitting next to him in shul. This way he would be safe and not embarrass himself. When his neighbor stood, he stood; when his neighbor sat, he sat. What the man near him turned a page, he too turned a page, etc.

All went smooth. Till at one point, the stranger to shul saw his neighbor stand up. So he too jumped up from his chair.

His neighbor turned to him and said: “Why are you embarrassing me in public? Sit down at once!”

“How I’m I embarrassing you?” wondered the newcomer. “I have been mimicking you all day long, what’s the problem?”

Don’t you realize? The man said. The Rabbi just announced: “Will the father of the new baby please rise. Well, my wife and I just had a baby a few days ago, so I stood up. Now, to my great disgrace, you stand up too...”

The Scroll

On Simchat Torah, the host of the party (the Baal Simcha), is the Sefer Torah, the Torah Scroll. It is his holiday. We take out the Torah, we dance with it. We become its legs. The greatest honor is to have a chance to hold a Sefer Torah, to hug it, to kiss it, to feel it, to rejoice in the joy of the Torah.

Today I want to talk about the physical anatomy of the Sefer Torah, and how appreciating the characteristics of the physical Sefer Torah will allow us to appreciate the lives and values of our parents and grandparents who we will soon be saying Yizkor for and remembering today.

The Printing Revolution

In an age where even printed newspapers and books are struggling to survive in face of the technological revolution, the information age, the internet, and all of Steve Jobs’ products, the Torah Scroll remains an anomaly. Not only can’t it be used on a Kindle, or on an i-pad, but furthermore, we can’t even read it from a printed book. It must be written on ancient parchment, and then all the parchment pages are sewn together creating the Torah Scroll. Why?

The first printing press was invented by a German Jew, Johannes Gutenberg, around 1450, and it changed civilization. It brought knowledge to the masses, increased literacy and spread information. Interestingly, the first mass-produced book was the Gutenburg Bible. There are 21 complete copies left in existence, and these are widely regarded as the most expensive books in the world, with an estimated price of 35 million dollars (the last time one has been sold was in 1978.)

The printing revolution affected especially the Jewish world. Until the invention of the printing press, Hebrew books were very scarce, as they were produced laboriously by copying from one manuscript to another. Yet unlike the leaders of the Catholic Church, who tried to stop the dissemination of printed books, Rabbinic leaders were highly enthusiastic about the new technology, and considered the craft of printing Avodat ha-Kodesh (holy work). The first Hebrew book was published in Rome in 1470—fourteen years after Gutenberg printed his famous Bible. It was Rashi’s commentary on the Bible. By 1500, eight years after the Jewish expulsion from Spain, 180 Hebrew titles were issued.

And yet, notwithstanding the blessings of the printing press embraced so enthusiastically by Jews, the Sefer Torah—the Torah Scroll—remains a loner. Till today, 2011, if we want to read form the Torah in the synagogue, it has to be written on a scroll. The Sefer Torah is a living reminder of the way information has been transmitted for four millennia: texts written on scrolls of parchment.

Why the bother of a scribe laboring for more than a year to write the close to 40,000 letters in the Torah with his hand, ink on parchment? This is not only to avoid error. Today with the computer we can produce a perfect error-free Torah scroll in seconds. It is rather to demonstrate the authenticity of the product. Our Torah scroll is an exact copy of a previous one, all the way back to Moses. Moses, in his last days, personally wrote a Torah scroll. If Moses would walk into this synagogue right now and read one of our Torahs, he would discover that letter for letter, word for word, spacing for spacing, this is exactly the same Torah that he personally wrote 3,284 years ago.

But there is something much deeper about the Torah Scroll. There is a lesson in the anatomy of the scroll vs. the book which the Torah wanted us to maintain even in the 21st century.

The History of Mankind Reflected in Books

The Torah states in Genesis, the portion that will be read this coming Shabbos:

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man.

This does not only mean that the Torah records human history; but rather that the very book embodies the history of mankind. If we study the history of the book, we will glean insight into the history of mankind. What is fascinating is that where ancient man is characterized by his scroll, modern man has become like his book.

Three Distinctions

There are three primary differences between the modern book (in print or on Kindle or on the internet) and the ancient scroll.

First of all, in a scroll, when you roll it open, you can already the subsequent pages till the final page, even when you are still holding at the first page. In a book, you can only see each page alone at a time. Only when you conclude one page, can you turn the page, leaving behind that page and exposing what is next.

The second difference is that a scroll is written always only on one side of the parchment, with the flip side remaining blank. A book is always printed on both sides of the page. And on each side there is a different message.

A final major difference is that there is no automatic copying system for scrolls and Sefer Torah’s. Each one must be written painstakingly and individually. Hence, if there is an error that creeps into one scroll, that error might not make it into the second scroll which will be written independently of the first.

Books, on the other hand, are printed using a universal typeset and in an automated system that allows for mass production. If a book has a mistake, then that will mean inevitably that this exact mistake will be found in every other book from this same press.

Ancient Man and Modern Man

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man. The very book embodies the history of mankind.

People used to be like scrolls, but now they are like books—in all three counts.

It used to be that we looked at our lives in a broader perspective, and like a scroll, saw the end initially at the beginning. The human being focused on his or her final destination more than on his present conditions. What was important to man was not the temporary conditions of the here and now, but rather his legacy, his offspring, his family line, how he would be remembered. Man looked a hundred years down the road, or even a thousand years, and made decisions based on what was a priority in a more universal and long-term facts and conditions.

This was not only a Jewish characteristic. Even Laban, the wicked Pagan brother of Rebecca, understood this truth. It is a fascinating and telling moment in Genesis. When Rebecca left to marry Isaac, Laban blessed her as follows: "My sister! May you and your offspring number in the thousands of myriads!" (Genesis 24:60) Laban understood that the future was more important than the present. He did not bless her with wealth, comfort, or a beautiful home, coach and jewelry. Even the scheming Laban saw life from a more global, long term, perspective.

Today we often “behave” like books. We see only as far as the end of the page we are reading, no more. We have become short sighted, not having the courage to attempt to ask the hard questions and provide the tough answers. "How do I want my grandchildren to look?" "How do I want to be remembered? What are the true values that I would have inscribed on my tombstone?" We do no try to picture the end of the story, where the decisions of our youth will take us in life. We seek instant comfort at the expense of long term values. Too many young adults today choose to remain single while enjoying their freedom and independence, and only years later regret the lost opportunity to build families.

You know the anecdote:

Two confirmed bachelors sat talking, their conversation drifted from politics to cooking. "I got a cookbook once," said one, "but I could never do anything with it." "Too much fancy work in it, eh?" asked the other. "You said it. Every one of the recipes began the same way: 'Take a clean dish.’"

Too many couples choose not to have children, or to have only one child, so they can build their careers, but when they grow older, they realize how they erred.

Man today is often unconcerned with the tomorrow, with the future of his life, and works primarily for the comfort of the present. Our parents and grandparents had the strength and stamina to disregard even the tough conditions of the present for the sake of investing in the long-term benefits of the future.

A Son’s Eulogy

A rabbi recently shared an experience he had at a funeral which he officiated at.

The eulogy was delivered by the deceased’s son. From his words we understood that their relationship had its problems. But then tears rolled down his cheeks as he spoke of his father’s patience and love and trust, and asked for forgiveness. He then said, “Dad, I hope it’s not too late to tell you these words that I always felt about you but never told you in person.”

And in a very soft, delicate voice, choking with emotion, he recited the words from the Bette Midler song, “Wind Beneath My Wings:” “Did you ever know that you’re my hero? And everything I’d like to be… that I can fly higher than an eagle, but you are the wind beneath my wings. It might have appeared to go unnoticed, but I got it all here in my heart… thank you, thank you, thank G-d for you, the wind beneath my wings.”

There was not a dry eye in the crowd. Here was a son whose relationship with his father was complicated. He had to wait till the funeral to tell this to his dad. Those words touched all those who were present, reminding them of the significant role that parents play in the lives of their children and how oftentimes it goes unexpressed and seemingly unappreciated until it’s too late.

As we remember today our loved ones who passed, we have to ask ourselves: What are the memories we are creating for our children? Will I spend my life arguing and fighting with my kids because of short-term disagreements? Or will I see the bigger picture, and embrace my children with endless and eternal love that they can then transfer to further generations? Will I be a book or will I be a scroll?

Fakeness

The second difference between a scroll and a book is if it is on one side or two sides. Like a one-sided scroll, people used to be one sided, meaning, honest, straight-forward and direct; they did not have two different messages on the two sides of their life’s page. What you saw is what you got. People were outspoken and blunt, in a refreshing way. Today we are often double-sided like the pages of books. And on every side there is a different message. If you look at me from one side you will see one thing; if you look at me from another side, you will see something very different.

Individuality

Finally, in the earlier generations each scroll was written by a special scribe and each scroll was an original piece of artwork. People were individuals, characters, each paving his or her own way in life. People were original, each one an innovation.

Today, thousands of books are printed as one, giving all of them a single face. Today, we all mimic each other; we all speak, act and look alike. We conform, and do not have the courage to be different. We copy each others virtues and vices, because there is safety in numbers, and this is the way we avoid accountability.

Cherish the Scroll

This is why a Sefer Torah, or a Megillah, in order to be read in the Synagogue, have to be written on scrolls, and are invalid if printed in a book. Notwithstanding the virtues of the printing press, we don’t want to become books, but we want to remain also “scrolls.” And this is what the Torah, and the Torah scroll, tried to teach us,

A Jew who lives life based on Torah, lives with values of the future, of the long-term. He or she thinks of the tomorrow, and not only the tomorrow of this world, but also of the next. Are you living a life that you will be proud of after your passing? Are you nurturing your soul, or only your body? The body will die, but the soul is eternal. What are you doing for your soul?

Torah does not allow man to forget about future, about the bigger picture, about the great family values, about the soul, about the Judaism of our grandchildren.

In addition, Torah despises fakeness. Torah demands integrity of the highest order. Finally, the Torah cherishes true individuality. And it gives a person the courage to maintain stand up to the society around him, and not to bend to peer pressure. A person must be loyal to his own soul, to his heart, and to his own G-d.

As we remember our loved ones during Yizkor, we need to ask ourselves this question: Have I become a book, or I’m I still a scroll, serving as the “feet” to the Torah Scroll I will hold and dance? I’m I thinking about the bigger picture of life? I’m I a real person, living with true honesty and integrity? And finally, I’m I living a life true to my individual and unique potential? I’m I fulfilling the mission for which I was created?

***

Appendix: The Parents Cheering

Rabbi Sholom Moshe Paltiel (Port Washington, NY) shared the following story:

I was visiting Jewish patients in S. Francis Hospital some months back, when I walked into the room of an elderly Jew named Irving, a holocaust survivor, who was obviously quite sick, surrounded by his entire family. I spent some time with him. We talked about the horrors of his youth, and how he managed to continue on living. He told me it was his mother's words to him on the last night before we were separated. "She sat me down and said to me: Life is like a play. (My mother loved the theater). Every one of us plays a part. Not just us, but our parents and grandparents, they're parents and grandparents, all the way back to Abraham and Sarah. They're all part of this production. Each of us plays a part, And then, when your part is over, you go backstage. You're not gone, you're still there, looking, cheering, helping out in any way you can from behind the scenes."

And then mama grabbed my hand, looked me in the eye, and said: "Yisrolik, I don't know what's going to happen, how long we'll be together, whether I'll survive this. But one thing I ask of you, If you survive. Don't give up, play your part. You might feel sad and lonely, but I beg of you- don't give up. Play your role as best you can. Live your life to the fullest. I promise you, you won't be alone. Tate un ich, babe un zeide, mir velen aleh zein mit dir oif eibig, Daddy and me, grandma and grandpa, we will be with you forever, we'll be watching you from backstage. I'm sure you won't let us down and you'll play your part." It was those words from Mama that got me out of bed on many a difficult morning.

By the time the man finished the story, there wasn't a dry eye in the room.

A few days later the man passed away. At the shiva, the family kept repeating the story about the play. It was clear they took comfort from knowing their father was still there, behind the scenes. Still, there was a profound sense of pain and loss.

They asked me to say a few words. So I got up, turned to the family, and I said: There is a postscript to the story. What happens at the end of the play? All the actors comes back out. Right? Everyone comes out on the stage to give a bow. It is a basic Jewish belief that all the neshomos, every soul will come back and be with us once again, right here in this world. I assure you, I said, with G-d's help, you will soon be reunited with your father."

My dear beloved friends, my fellow yiden, we're about to say the Yiskor prayer. Remembering our loved ones whose souls join us right here in shul. Let's promise to make them proud. Let's make this the year when each of us reaches our potential, when each of us lives each day to the fullest, When we realize the beauty of every moment. when we appreciate the G-dly purpose we have been privileged to be a part of.

And while we're at it, let's ask our loved one's to send an email or put in a phone call to the producer, Or maybe even pay Him a visit. Tell Him, please. We're ready for Moshiach. We've done our job. Enough with the yiddishe tzoros, shoin tzeit, it's time already. We're ready for the time when, as we say in the Alanu prayer, “lecho tichra kol berech,” all creations will bow to you. We're ready for the final bow.

Categories

Shemini Atzeres/Simchas Torah 5772

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 12, 2011

- |

- 14 Tishrei 5772

- |

- 15 views

Yizkor: 3 Principles of Good Living

The Book Vs. the Scroll: The Secret of the Sefer Torah

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 12, 2011

“I’m Not From Here”

You know the story about the rabbi who in the middle of his Yizkor sermon on Yom Kippur, pounds on the table and says ‘Wake up to the fact that every single person in this congregation, myself included, is going to die!”

And as he expected, everyone’s suddenly very alarmed, except for one man in the third row whose face breaks out into a broad smile.

And the rabbi is so shocked, he points to this man and says, “so why are you so amused?”

And the man shrugs his shoulders and answers, “Well I’m not from this congregation. I’m just visiting my sister.”

Don’t Shame Me

A very assimilated Jew who was never in synagogue before came on Yom Kippur to the synagogue for the first time in his life.

Since he did not know what to do, he decided to emulate the person sitting next to him in shul. This way he would be safe and not embarrass himself. When his neighbor stood, he stood; when his neighbor sat, he sat. What the man near him turned a page, he too turned a page, etc.

All went smooth. Till at one point, the stranger to shul saw his neighbor stand up. So he too jumped up from his chair.

His neighbor turned to him and said: “Why are you embarrassing me in public? Sit down at once!”

“How I’m I embarrassing you?” wondered the newcomer. “I have been mimicking you all day long, what’s the problem?”

Don’t you realize? The man said. The Rabbi just announced: “Will the father of the new baby please rise. Well, my wife and I just had a baby a few days ago, so I stood up. Now, to my great disgrace, you stand up too...”

The Scroll

On Simchat Torah, the host of the party (the Baal Simcha), is the Sefer Torah, the Torah Scroll. It is his holiday. We take out the Torah, we dance with it. We become its legs. The greatest honor is to have a chance to hold a Sefer Torah, to hug it, to kiss it, to feel it, to rejoice in the joy of the Torah.

Today I want to talk about the physical anatomy of the Sefer Torah, and how appreciating the characteristics of the physical Sefer Torah will allow us to appreciate the lives and values of our parents and grandparents who we will soon be saying Yizkor for and remembering today.

The Printing Revolution

In an age where even printed newspapers and books are struggling to survive in face of the technological revolution, the information age, the internet, and all of Steve Jobs’ products, the Torah Scroll remains an anomaly. Not only can’t it be used on a Kindle, or on an i-pad, but furthermore, we can’t even read it from a printed book. It must be written on ancient parchment, and then all the parchment pages are sewn together creating the Torah Scroll. Why?

The first printing press was invented by a German Jew, Johannes Gutenberg, around 1450, and it changed civilization. It brought knowledge to the masses, increased literacy and spread information. Interestingly, the first mass-produced book was the Gutenburg Bible. There are 21 complete copies left in existence, and these are widely regarded as the most expensive books in the world, with an estimated price of 35 million dollars (the last time one has been sold was in 1978.)

The printing revolution affected especially the Jewish world. Until the invention of the printing press, Hebrew books were very scarce, as they were produced laboriously by copying from one manuscript to another. Yet unlike the leaders of the Catholic Church, who tried to stop the dissemination of printed books, Rabbinic leaders were highly enthusiastic about the new technology, and considered the craft of printing Avodat ha-Kodesh (holy work). The first Hebrew book was published in Rome in 1470—fourteen years after Gutenberg printed his famous Bible. It was Rashi’s commentary on the Bible. By 1500, eight years after the Jewish expulsion from Spain, 180 Hebrew titles were issued.

And yet, notwithstanding the blessings of the printing press embraced so enthusiastically by Jews, the Sefer Torah—the Torah Scroll—remains a loner. Till today, 2011, if we want to read form the Torah in the synagogue, it has to be written on a scroll. The Sefer Torah is a living reminder of the way information has been transmitted for four millennia: texts written on scrolls of parchment.

Why the bother of a scribe laboring for more than a year to write the close to 40,000 letters in the Torah with his hand, ink on parchment? This is not only to avoid error. Today with the computer we can produce a perfect error-free Torah scroll in seconds. It is rather to demonstrate the authenticity of the product. Our Torah scroll is an exact copy of a previous one, all the way back to Moses. Moses, in his last days, personally wrote a Torah scroll. If Moses would walk into this synagogue right now and read one of our Torahs, he would discover that letter for letter, word for word, spacing for spacing, this is exactly the same Torah that he personally wrote 3,284 years ago.

But there is something much deeper about the Torah Scroll. There is a lesson in the anatomy of the scroll vs. the book which the Torah wanted us to maintain even in the 21st century.

The History of Mankind Reflected in Books

The Torah states in Genesis, the portion that will be read this coming Shabbos:

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man.

This does not only mean that the Torah records human history; but rather that the very book embodies the history of mankind. If we study the history of the book, we will glean insight into the history of mankind. What is fascinating is that where ancient man is characterized by his scroll, modern man has become like his book.

Three Distinctions

There are three primary differences between the modern book (in print or on Kindle or on the internet) and the ancient scroll.

First of all, in a scroll, when you roll it open, you can already the subsequent pages till the final page, even when you are still holding at the first page. In a book, you can only see each page alone at a time. Only when you conclude one page, can you turn the page, leaving behind that page and exposing what is next.

The second difference is that a scroll is written always only on one side of the parchment, with the flip side remaining blank. A book is always printed on both sides of the page. And on each side there is a different message.

A final major difference is that there is no automatic copying system for scrolls and Sefer Torah’s. Each one must be written painstakingly and individually. Hence, if there is an error that creeps into one scroll, that error might not make it into the second scroll which will be written independently of the first.

Books, on the other hand, are printed using a universal typeset and in an automated system that allows for mass production. If a book has a mistake, then that will mean inevitably that this exact mistake will be found in every other book from this same press.

Ancient Man and Modern Man

זה ספר תולדות אדם.

This is the Book of the Story of Man. The very book embodies the history of mankind.

People used to be like scrolls, but now they are like books—in all three counts.

It used to be that we looked at our lives in a broader perspective, and like a scroll, saw the end initially at the beginning. The human being focused on his or her final destination more than on his present conditions. What was important to man was not the temporary conditions of the here and now, but rather his legacy, his offspring, his family line, how he would be remembered. Man looked a hundred years down the road, or even a thousand years, and made decisions based on what was a priority in a more universal and long-term facts and conditions.

This was not only a Jewish characteristic. Even Laban, the wicked Pagan brother of Rebecca, understood this truth. It is a fascinating and telling moment in Genesis. When Rebecca left to marry Isaac, Laban blessed her as follows: "My sister! May you and your offspring number in the thousands of myriads!" (Genesis 24:60) Laban understood that the future was more important than the present. He did not bless her with wealth, comfort, or a beautiful home, coach and jewelry. Even the scheming Laban saw life from a more global, long term, perspective.

Today we often “behave” like books. We see only as far as the end of the page we are reading, no more. We have become short sighted, not having the courage to attempt to ask the hard questions and provide the tough answers. "How do I want my grandchildren to look?" "How do I want to be remembered? What are the true values that I would have inscribed on my tombstone?" We do no try to picture the end of the story, where the decisions of our youth will take us in life. We seek instant comfort at the expense of long term values. Too many young adults today choose to remain single while enjoying their freedom and independence, and only years later regret the lost opportunity to build families.

You know the anecdote:

Two confirmed bachelors sat talking, their conversation drifted from politics to cooking. "I got a cookbook once," said one, "but I could never do anything with it." "Too much fancy work in it, eh?" asked the other. "You said it. Every one of the recipes began the same way: 'Take a clean dish.’"

Too many couples choose not to have children, or to have only one child, so they can build their careers, but when they grow older, they realize how they erred.

Man today is often unconcerned with the tomorrow, with the future of his life, and works primarily for the comfort of the present. Our parents and grandparents had the strength and stamina to disregard even the tough conditions of the present for the sake of investing in the long-term benefits of the future.

A Son’s Eulogy

A rabbi recently shared an experience he had at a funeral which he officiated at.

The eulogy was delivered by the deceased’s son. From his words we understood that their relationship had its problems. But then tears rolled down his cheeks as he spoke of his father’s patience and love and trust, and asked for forgiveness. He then said, “Dad, I hope it’s not too late to tell you these words that I always felt about you but never told you in person.”

And in a very soft, delicate voice, choking with emotion, he recited the words from the Bette Midler song, “Wind Beneath My Wings:” “Did you ever know that you’re my hero? And everything I’d like to be… that I can fly higher than an eagle, but you are the wind beneath my wings. It might have appeared to go unnoticed, but I got it all here in my heart… thank you, thank you, thank G-d for you, the wind beneath my wings.”

There was not a dry eye in the crowd. Here was a son whose relationship with his father was complicated. He had to wait till the funeral to tell this to his dad. Those words touched all those who were present, reminding them of the significant role that parents play in the lives of their children and how oftentimes it goes unexpressed and seemingly unappreciated until it’s too late.

As we remember today our loved ones who passed, we have to ask ourselves: What are the memories we are creating for our children? Will I spend my life arguing and fighting with my kids because of short-term disagreements? Or will I see the bigger picture, and embrace my children with endless and eternal love that they can then transfer to further generations? Will I be a book or will I be a scroll?

Fakeness

The second difference between a scroll and a book is if it is on one side or two sides. Like a one-sided scroll, people used to be one sided, meaning, honest, straight-forward and direct; they did not have two different messages on the two sides of their life’s page. What you saw is what you got. People were outspoken and blunt, in a refreshing way. Today we are often double-sided like the pages of books. And on every side there is a different message. If you look at me from one side you will see one thing; if you look at me from another side, you will see something very different.

Individuality

Finally, in the earlier generations each scroll was written by a special scribe and each scroll was an original piece of artwork. People were individuals, characters, each paving his or her own way in life. People were original, each one an innovation.

Today, thousands of books are printed as one, giving all of them a single face. Today, we all mimic each other; we all speak, act and look alike. We conform, and do not have the courage to be different. We copy each others virtues and vices, because there is safety in numbers, and this is the way we avoid accountability.

Cherish the Scroll

This is why a Sefer Torah, or a Megillah, in order to be read in the Synagogue, have to be written on scrolls, and are invalid if printed in a book. Notwithstanding the virtues of the printing press, we don’t want to become books, but we want to remain also “scrolls.” And this is what the Torah, and the Torah scroll, tried to teach us,

A Jew who lives life based on Torah, lives with values of the future, of the long-term. He or she thinks of the tomorrow, and not only the tomorrow of this world, but also of the next. Are you living a life that you will be proud of after your passing? Are you nurturing your soul, or only your body? The body will die, but the soul is eternal. What are you doing for your soul?

Torah does not allow man to forget about future, about the bigger picture, about the great family values, about the soul, about the Judaism of our grandchildren.

In addition, Torah despises fakeness. Torah demands integrity of the highest order. Finally, the Torah cherishes true individuality. And it gives a person the courage to maintain stand up to the society around him, and not to bend to peer pressure. A person must be loyal to his own soul, to his heart, and to his own G-d.

As we remember our loved ones during Yizkor, we need to ask ourselves this question: Have I become a book, or I’m I still a scroll, serving as the “feet” to the Torah Scroll I will hold and dance? I’m I thinking about the bigger picture of life? I’m I a real person, living with true honesty and integrity? And finally, I’m I living a life true to my individual and unique potential? I’m I fulfilling the mission for which I was created?

***

Appendix: The Parents Cheering

Rabbi Sholom Moshe Paltiel (Port Washington, NY) shared the following story:

I was visiting Jewish patients in S. Francis Hospital some months back, when I walked into the room of an elderly Jew named Irving, a holocaust survivor, who was obviously quite sick, surrounded by his entire family. I spent some time with him. We talked about the horrors of his youth, and how he managed to continue on living. He told me it was his mother's words to him on the last night before we were separated. "She sat me down and said to me: Life is like a play. (My mother loved the theater). Every one of us plays a part. Not just us, but our parents and grandparents, they're parents and grandparents, all the way back to Abraham and Sarah. They're all part of this production. Each of us plays a part, And then, when your part is over, you go backstage. You're not gone, you're still there, looking, cheering, helping out in any way you can from behind the scenes."

And then mama grabbed my hand, looked me in the eye, and said: "Yisrolik, I don't know what's going to happen, how long we'll be together, whether I'll survive this. But one thing I ask of you, If you survive. Don't give up, play your part. You might feel sad and lonely, but I beg of you- don't give up. Play your role as best you can. Live your life to the fullest. I promise you, you won't be alone. Tate un ich, babe un zeide, mir velen aleh zein mit dir oif eibig, Daddy and me, grandma and grandpa, we will be with you forever, we'll be watching you from backstage. I'm sure you won't let us down and you'll play your part." It was those words from Mama that got me out of bed on many a difficult morning.

By the time the man finished the story, there wasn't a dry eye in the room.

A few days later the man passed away. At the shiva, the family kept repeating the story about the play. It was clear they took comfort from knowing their father was still there, behind the scenes. Still, there was a profound sense of pain and loss.

They asked me to say a few words. So I got up, turned to the family, and I said: There is a postscript to the story. What happens at the end of the play? All the actors comes back out. Right? Everyone comes out on the stage to give a bow. It is a basic Jewish belief that all the neshomos, every soul will come back and be with us once again, right here in this world. I assure you, I said, with G-d's help, you will soon be reunited with your father."

My dear beloved friends, my fellow yiden, we're about to say the Yiskor prayer. Remembering our loved ones whose souls join us right here in shul. Let's promise to make them proud. Let's make this the year when each of us reaches our potential, when each of us lives each day to the fullest, When we realize the beauty of every moment. when we appreciate the G-dly purpose we have been privileged to be a part of.

And while we're at it, let's ask our loved one's to send an email or put in a phone call to the producer, Or maybe even pay Him a visit. Tell Him, please. We're ready for Moshiach. We've done our job. Enough with the yiddishe tzoros, shoin tzeit, it's time already. We're ready for the time when, as we say in the Alanu prayer, “lecho tichra kol berech,” all creations will bow to you. We're ready for the final bow.

- Comment

Class Summary:

In an age where even printed newspapers and books are struggling to survive in face of the technological revolution, the information age, the internet, and all of Steve Jobs’ products, the Torah Scroll remains an anomaly. Not only can’t it be used on a Kindle, or on an i-pad, but furthermore, we can’t even read it from a printed book. It must be written on ancient parchment, and then all the parchment pages are sewn together creating the Torah Scroll. Why?

The 15th century saw the revolution of the printing press which changed civilization. Yet Judaism demands that the Torah still be written as an ancient scroll, because the three distinctions between a scroll and a book embody the three major distinctions between ancient and modern man.

As we remember our loved ones during Yizkor, we need to ask ourselves this question: Have I become a book, or I’m I still a scroll, serving as the “feet” to the Torah Scroll I will hold and dance? I’m I thinking about the bigger picture of life? I’m I a real person, living with true honesty and integrity? And finally, I’m I living a life true to my individual and unique potential? I’m I fulfilling the mission for which I was created?

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!