The Insanity of the Human Psyche

A Vision of G-d and a Mountain of Dust

- May 19, 2016

- |

- 11 Iyyar 5776

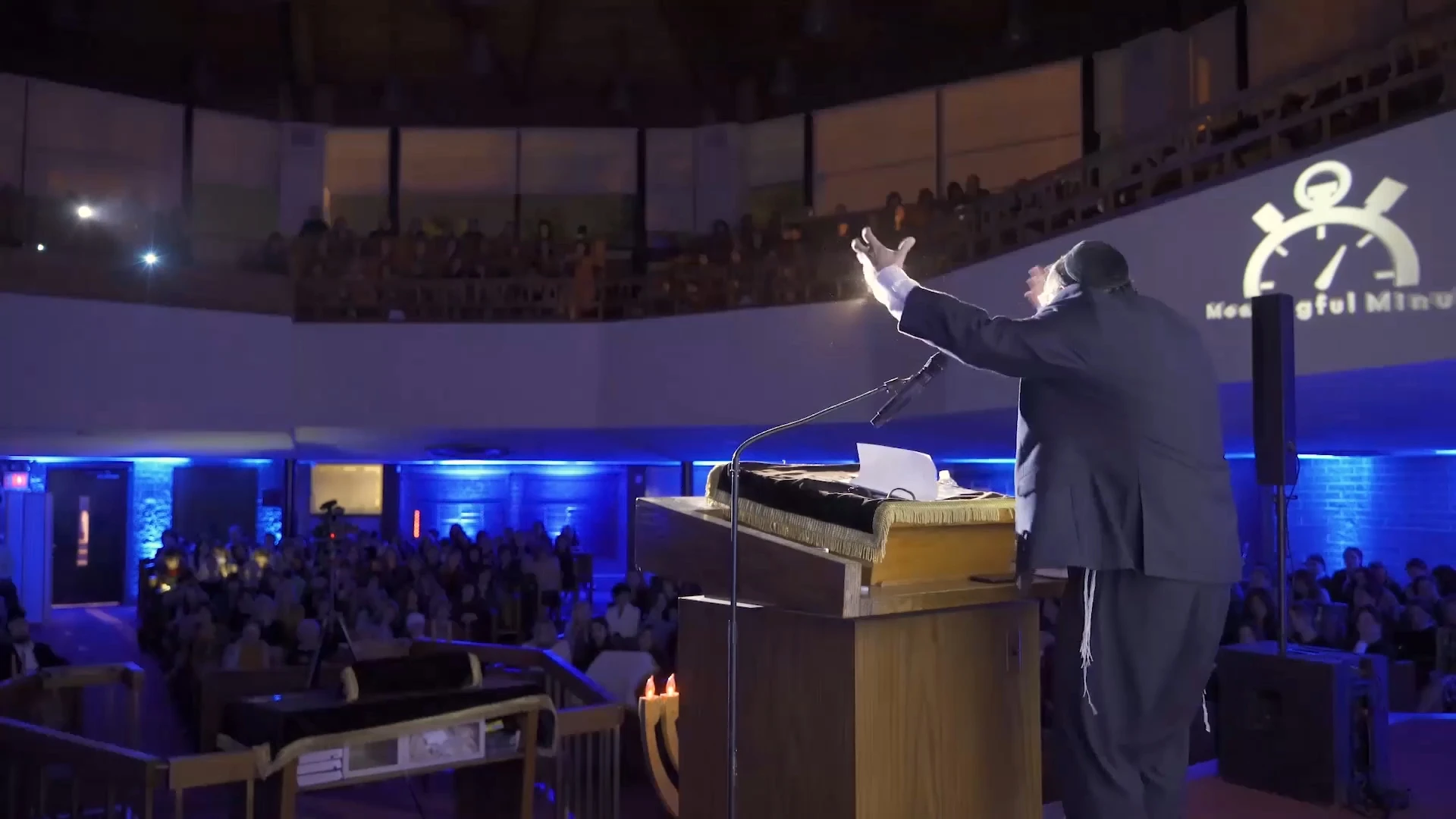

Rabbi YY Jacobson

3368 views

Split in the human psyche

The Insanity of the Human Psyche

A Vision of G-d and a Mountain of Dust

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 19, 2016

Two Extra Guests

A Jewish couple won the lottery. They immediately set out to begin a life of luxury. They bought a magnificent mansion in Knightsbridge and surrounded themselves with all the material wealth imaginable.

Then they decided to hire a butler. They found the perfect butler through an agency, very proper and very British, and brought him back to their home. The day after his arrival, he was instructed to set up the dining room table for four, as they were inviting the Cohens to lunch. The couple then left the house to do some shopping.

When they returned, they found the table set for eight. They asked the butler why eight, when they had specifically instructed him to set the table for four?

The butler replied, "The Cohens telephoned and said they were bringing the Blintzes and the Knishes."Marriage of the High Priest

An astonishing and sobering contrast concerning the nature of the human psyche captures our imagination in this week’s Torah portion, Emor.

The Torah prohibits a Kohen, a priest (which includes all descendents of Aaron), from marrying a divorced woman. It also prohibits a Kohen Gadol, a High Priest, from marrying a divorcee and a widow (1).

Now, one can perhaps make sense out of the former prohibition: Since a priest served as the spiritual agent of the Jewish people in Divine service, he was required to live a life of complete innocence and purity. Therefore, the Torah did not want him marrying a person involved in strife, innocent or not.

But why could the High Priest not marry a widow? What is it about her husband's death that makes her unqualified to enjoy a blessed relationship with a Jewish High Priest?

Several answers have been given to this question (2). In this essay I want to share with you one answer that I have always found extremely disturbing yet comforting, as it depicts how Judaism does not hide its face from the profound struggles confronting the human life.

Abuse of spiritual powerRabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulaei, an 18th century sage and mystic known in short as the Chida (3), presents the following interpretation in the name of the great 12th century Jewish pietistic sage, Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid (4).

The High Priest of Israel was given many great spiritual powers. The most important of them was his duty on the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, to enter into the Temple's Holy of Holies, a place where no other living Jew was ever allowed to enter.

On that charged day, the High Priest would also pronounce the intimate 72-letter name of G-d, which contained very profound powers. (The Jewish Sages intentionally ceased teaching that name during the period of the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, and it has since been forgotten.)

Now, the Torah is concerned that the High Priest may experience infatuation with a particular married woman. What might he do about the fact of her being married? Next Yom Kippur, he will utilize the moment when he utterance G-d's ineffable name in order to bring about a decree of death on her husband (5). Thus he would be free to marry the widow.

It is as a result of this concern that the Torah commands that a High Priest may not marry a widow. Even if he succeeds in getting rid of the husband, he would not be able to marry the wife. “Do not try pulling off this one,” the Torah informs the High Priest, “it won’t get you anywhere.”

This is shocking idea. On the holiest day of the year, in the holiest place on earth, we are concerned that the man designated to serve in the highest spiritual and holiest position of Israel, while uttering the holiest syllables in the world, might harbor a craving to eliminate an innocent man so that he can marry his wife!How can this be?

Angelic heights

Now, let us contrast this with another biblical statement concerning the High Priest entering into the Sanctuary on Yom Kippur, also from the book of Leviticus:

“No human being shall be in the Tent of Meeting when he [the High Priest] comes to provide atonement in the Sanctuary, until his departure (6).” Not only were there no Blintzes and Knishes allowed during the Yom Kippur service, but also no Cohen’s or any other people were allowed to be present at the time.

The Midrash (7), in its sensitivity to biblical nuance, wonders how can the Bible state that no human being should be present at the time of the High Priest’s service on Yom Kippur, when the High Priest himself was a human being? At least one man was present!

The Midrash answers that when the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies he was not human indeed; he assumed the status of a Heavenly Angel. Indeed, no human being entered the Sanctuary with him; not even his own.

What is going on here? We are confronted with an uneasy contradiction. One biblical source indicates the potential mind-staggering lowliness of a High Priest, capable of descending into the lowest depths of depraved behavior, while the other biblical source intimates his potential for enormous spiritual heights, capable of transcending the human experience and reaching angelic heights. How do we reconcile the two? Who is the High Priest, the holiest of the holy or the lowliest of the lowly?

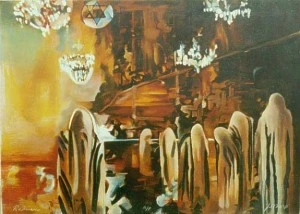

Dust and image

Yet it is here we encounter, once again, Judaism’s moving perspective on the nature of the human being. There are two ways in which the Bible speaks of the creation of man. In the first chapter of Genesis, man is described as having been created in the image and likeness of G-d. In the second chapter, man is described as having been formed out of the dust of the earth. Together, image and dust express the polarity of the nature of man. He is formed of the most inferior stuff in the most superior image.

The author of life and of mankind knew full well that sexuality holds men -- priests and lay men alike -- captive in its enormously powerful grip. Even the greatest of men are capable of falling prey to its momentous temptation. Even a High Priest, on the holiest day of the year, in the holiest space of the world, while uttering the holiest word in the world, is capable of thinking grotesque thoughts about how he can "bump a man off the road" so that he can lay his hands on his woman. Judaism has always been keenly sensitive to the truth that every human being has a demon lurking within. If you don't challenge and tame it each day anew, it can turn you into a monster; you are capable of ugliness in the least expected circumstances.But the author of life also knew that the human person is capable of incredible greatness. The soul of man being a “fragment of G-d (8),” he or she is capable of generating infinite goodness and encountering within themselves infinite idealism. As Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel, a scion of the great Chassidic masters, once put it, “Man is a polarity of a divine image and worthless dust. He is a duality of mysterious grandeur and pompous aridity, a vision of G-d and a mountain of dust. It is because of his being dust that his iniquities may be forgiven, and it is because of his being an image that his holiness and idealism is expected.”

So, the next time you are overtaken by challenging cravings, addictions, temptations and any negative feelings, do not fall into despair. Remember, you are no worse than the High Priest of Israel! You, too, may struggle against horrible demons. But, you, too, may still enter into the Holy of Holies.

It is up to each of us to define who we are. The rest will become a self fulfilling prophesy.

1) Leviticus 21:7; 14. 2) See, for example, Sefer Hachenuch Parshas Emor; Mai Hasheluach vol. 2 Parshas Emor.

3) 1724-1806. The Chida, author of more than 50 volumes on Torah thought, was one of the great Torah luminaries of his day. He resided in Israel, Egypt and Italy. He quotes this interpretation in his book Penei David. The following explanation is also quoted in Moshav Zekanaim Al Hatorah (by the French 13th century authors of the Tosefot on the Talmud) in the name of “the Chassid.

Parenthetically, in an Emor essay by Rabbi Yissachar Frond he quotes Rabbi Bergman as stating that the above mentioned “Chassid” quoted in Moshav Zekanim refers to The Rokeach (this is the 13th century German mystic and sage, Rabbi Eliezer Rokeach). Yet, based on the explicit reference given by the Chida, I think the Moshav Zekanim is referring to Reb Yehudah Hachasid.

It should also be noted that the Chida himself rejects this interpretation in Penei David ibid.

4) Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid, who resided in Regensburg, Germany and authored the famed Sefer Chassidim, was known as one of the great kabbalists and Halachik authorities of his day.

5) This (according to one opinion in Midrash) is what Moses did when he wishes to kill the Egyptian who was beating a Jew (Exodus 2:14 and Midrash Tanchumah ibid. Quoted in Rashi ibid.) 6) Leviticus 16:17. 7) Midrash Rabah to Leviticus ibid. 8) Of course, not every High Priest was suspected of this. The ideal High Priest was a Tzaddik in the deepest sense of the word, whose challenges and struggles are of a different nature (see Tanya ch. 10 about the true definition of a tzaddik). Yet, throughout our history, there have been many High Priests of a lower caliber. 9) See Ramban to Genesis ch. 2; introduction to Shefa Tal (a 17th century major Kabbalistic work by Rabbi Shabsi Sheptel Horowitz); Tanya ch. 2.- Comment

Class Summary:

Why could the High Priest not marry a widow? A daring interpretation by Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid teaches us how Judaism views human nature: our proclivity to moral failure, coupled with our ability for transcendence.

Two Extra Guests

A Jewish couple won the lottery. They immediately set out to begin a life of luxury. They bought a magnificent mansion in Knightsbridge and surrounded themselves with all the material wealth imaginable.

Then they decided to hire a butler. They found the perfect butler through an agency, very proper and very British, and brought him back to their home. The day after his arrival, he was instructed to set up the dining room table for four, as they were inviting the Cohens to lunch. The couple then left the house to do some shopping.

When they returned, they found the table set for eight. They asked the butler why eight, when they had specifically instructed him to set the table for four?

The butler replied, "The Cohens telephoned and said they were bringing the Blintzes and the Knishes."

Marriage of the High Priest

An astonishing and sobering contrast concerning the nature of the human psyche captures our imagination in this week’s Torah portion, Emor.

The Torah prohibits a Kohen, a priest (which includes all descendents of Aaron), from marrying a divorced woman. It also prohibits a Kohen Gadol, a High Priest, from marrying a divorcee and a widow (1).

Now, one can perhaps make sense out of the former prohibition: Since a priest served as the spiritual agent of the Jewish people in Divine service, he was required to live a life of complete innocence and purity. Therefore, the Torah did not want him marrying a person involved in strife, innocent or not.

But why could the High Priest not marry a widow? What is it about her husband's death that makes her unqualified to enjoy a blessed relationship with a Jewish High Priest?

Several answers have been given to this question (2). In this essay I want to share with you one answer that I have always found extremely disturbing yet comforting, as it depicts how Judaism does not hide its face from the profound struggles confronting the human life.

Abuse of spiritual power

Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulaei, an 18th century sage and mystic known in short as the Chida (3), presents the following interpretation in the name of the great 12th century Jewish pietistic sage, Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid (4).

The High Priest of Israel was given many great spiritual powers. The most important of them was his duty on the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, to enter into the Temple's Holy of Holies, a place where no other living Jew was ever allowed to enter.

On that charged day, the High Priest would also pronounce the intimate 72-letter name of G-d, which contained very profound powers. (The Jewish Sages intentionally ceased teaching that name during the period of the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, and it has since been forgotten.)

Now, the Torah is concerned that the High Priest may experience infatuation with a particular married woman. What might he do about the fact of her being married? Next Yom Kippur, he will utilize the moment when he utterance G-d's ineffable name in order to bring about a decree of death on her husband (5). Thus he would be free to marry the widow.

It is as a result of this concern that the Torah commands that a High Priest may not marry a widow. Even if he succeeds in getting rid of the husband, he would not be able to marry the wife. “Do not try pulling off this one,” the Torah informs the High Priest, “it won’t get you anywhere.”

This is shocking idea. On the holiest day of the year, in the holiest place on earth, we are concerned that the man designated to serve in the highest spiritual and holiest position of Israel, while uttering the holiest syllables in the world, might harbor a craving to eliminate an innocent man so that he can marry his wife!

How can this be?

Angelic heights

Now, let us contrast this with another biblical statement concerning the High Priest entering into the Sanctuary on Yom Kippur, also from the book of Leviticus:

“No human being shall be in the Tent of Meeting when he [the High Priest] comes to provide atonement in the Sanctuary, until his departure (6).” Not only were there no Blintzes and Knishes allowed during the Yom Kippur service, but also no Cohen’s or any other people were allowed to be present at the time.

The Midrash (7), in its sensitivity to biblical nuance, wonders how can the Bible state that no human being should be present at the time of the High Priest’s service on Yom Kippur, when the High Priest himself was a human being? At least one man was present!

The Midrash answers that when the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies he was not human indeed; he assumed the status of a Heavenly Angel. Indeed, no human being entered the Sanctuary with him; not even his own.

What is going on here? We are confronted with an uneasy contradiction. One biblical source indicates the potential mind-staggering lowliness of a High Priest, capable of descending into the lowest depths of depraved behavior, while the other biblical source intimates his potential for enormous spiritual heights, capable of transcending the human experience and reaching angelic heights. How do we reconcile the two? Who is the High Priest, the holiest of the holy or the lowliest of the lowly?

Dust and image

Yet it is here we encounter, once again, Judaism’s moving perspective on the nature of the human being. There are two ways in which the Bible speaks of the creation of man. In the first chapter of Genesis, man is described as having been created in the image and likeness of G-d. In the second chapter, man is described as having been formed out of the dust of the earth. Together, image and dust express the polarity of the nature of man. He is formed of the most inferior stuff in the most superior image.

The author of life and of mankind knew full well that sexuality holds men -- priests and lay men alike -- captive in its enormously powerful grip. Even the greatest of men are capable of falling prey to its momentous temptation. Even a High Priest, on the holiest day of the year, in the holiest space of the world, while uttering the holiest word in the world, is capable of thinking grotesque thoughts about how he can "bump a man off the road" so that he can lay his hands on his woman. Judaism has always been keenly sensitive to the truth that every human being has a demon lurking within. If you don't challenge and tame it each day anew, it can turn you into a monster; you are capable of ugliness in the least expected circumstances.

But the author of life also knew that the human person is capable of incredible greatness. The soul of man being a “fragment of G-d (8),” he or she is capable of generating infinite goodness and encountering within themselves infinite idealism. As Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel, a scion of the great Chassidic masters, once put it, “Man is a polarity of a divine image and worthless dust. He is a duality of mysterious grandeur and pompous aridity, a vision of G-d and a mountain of dust. It is because of his being dust that his iniquities may be forgiven, and it is because of his being an image that his holiness and idealism is expected.”

So, the next time you are overtaken by challenging cravings, addictions, temptations and any negative feelings, do not fall into despair. Remember, you are no worse than the High Priest of Israel! You, too, may struggle against horrible demons. But, you, too, may still enter into the Holy of Holies.

It is up to each of us to define who we are. The rest will become a self fulfilling prophesy.

1) Leviticus 21:7; 14. 2) See, for example, Sefer Hachenuch Parshas Emor; Mai Hasheluach vol. 2 Parshas Emor.

3) 1724-1806. The Chida, author of more than 50 volumes on Torah thought, was one of the great Torah luminaries of his day. He resided in Israel, Egypt and Italy. He quotes this interpretation in his book Penei David. The following explanation is also quoted in Moshav Zekanaim Al Hatorah (by the French 13th century authors of the Tosefot on the Talmud) in the name of “the Chassid.

Parenthetically, in an Emor essay by Rabbi Yissachar Frond he quotes Rabbi Bergman as stating that the above mentioned “Chassid” quoted in Moshav Zekanim refers to The Rokeach (this is the 13th century German mystic and sage, Rabbi Eliezer Rokeach). Yet, based on the explicit reference given by the Chida, I think the Moshav Zekanim is referring to Reb Yehudah Hachasid.

It should also be noted that the Chida himself rejects this interpretation in Penei David ibid.

4) Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid, who resided in Regensburg, Germany and authored the famed Sefer Chassidim, was known as one of the great kabbalists and Halachik authorities of his day.

5) This (according to one opinion in Midrash) is what Moses did when he wishes to kill the Egyptian who was beating a Jew (Exodus 2:14 and Midrash Tanchumah ibid. Quoted in Rashi ibid.) 6) Leviticus 16:17. 7) Midrash Rabah to Leviticus ibid. 8) Of course, not every High Priest was suspected of this. The ideal High Priest was a Tzaddik in the deepest sense of the word, whose challenges and struggles are of a different nature (see Tanya ch. 10 about the true definition of a tzaddik). Yet, throughout our history, there have been many High Priests of a lower caliber. 9) See Ramban to Genesis ch. 2; introduction to Shefa Tal (a 17th century major Kabbalistic work by Rabbi Shabsi Sheptel Horowitz); Tanya ch. 2.

Tags

Categories

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 19, 2016

- |

- 11 Iyyar 5776

- |

- 3368 views

The Insanity of the Human Psyche

A Vision of G-d and a Mountain of Dust

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 19, 2016

Two Extra Guests

A Jewish couple won the lottery. They immediately set out to begin a life of luxury. They bought a magnificent mansion in Knightsbridge and surrounded themselves with all the material wealth imaginable.

Then they decided to hire a butler. They found the perfect butler through an agency, very proper and very British, and brought him back to their home. The day after his arrival, he was instructed to set up the dining room table for four, as they were inviting the Cohens to lunch. The couple then left the house to do some shopping.

When they returned, they found the table set for eight. They asked the butler why eight, when they had specifically instructed him to set the table for four?

The butler replied, "The Cohens telephoned and said they were bringing the Blintzes and the Knishes."Marriage of the High Priest

An astonishing and sobering contrast concerning the nature of the human psyche captures our imagination in this week’s Torah portion, Emor.

The Torah prohibits a Kohen, a priest (which includes all descendents of Aaron), from marrying a divorced woman. It also prohibits a Kohen Gadol, a High Priest, from marrying a divorcee and a widow (1).

Now, one can perhaps make sense out of the former prohibition: Since a priest served as the spiritual agent of the Jewish people in Divine service, he was required to live a life of complete innocence and purity. Therefore, the Torah did not want him marrying a person involved in strife, innocent or not.

But why could the High Priest not marry a widow? What is it about her husband's death that makes her unqualified to enjoy a blessed relationship with a Jewish High Priest?

Several answers have been given to this question (2). In this essay I want to share with you one answer that I have always found extremely disturbing yet comforting, as it depicts how Judaism does not hide its face from the profound struggles confronting the human life.

Abuse of spiritual powerRabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulaei, an 18th century sage and mystic known in short as the Chida (3), presents the following interpretation in the name of the great 12th century Jewish pietistic sage, Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid (4).

The High Priest of Israel was given many great spiritual powers. The most important of them was his duty on the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, to enter into the Temple's Holy of Holies, a place where no other living Jew was ever allowed to enter.

On that charged day, the High Priest would also pronounce the intimate 72-letter name of G-d, which contained very profound powers. (The Jewish Sages intentionally ceased teaching that name during the period of the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, and it has since been forgotten.)

Now, the Torah is concerned that the High Priest may experience infatuation with a particular married woman. What might he do about the fact of her being married? Next Yom Kippur, he will utilize the moment when he utterance G-d's ineffable name in order to bring about a decree of death on her husband (5). Thus he would be free to marry the widow.

It is as a result of this concern that the Torah commands that a High Priest may not marry a widow. Even if he succeeds in getting rid of the husband, he would not be able to marry the wife. “Do not try pulling off this one,” the Torah informs the High Priest, “it won’t get you anywhere.”

This is shocking idea. On the holiest day of the year, in the holiest place on earth, we are concerned that the man designated to serve in the highest spiritual and holiest position of Israel, while uttering the holiest syllables in the world, might harbor a craving to eliminate an innocent man so that he can marry his wife!How can this be?

Angelic heights

Now, let us contrast this with another biblical statement concerning the High Priest entering into the Sanctuary on Yom Kippur, also from the book of Leviticus:

“No human being shall be in the Tent of Meeting when he [the High Priest] comes to provide atonement in the Sanctuary, until his departure (6).” Not only were there no Blintzes and Knishes allowed during the Yom Kippur service, but also no Cohen’s or any other people were allowed to be present at the time.

The Midrash (7), in its sensitivity to biblical nuance, wonders how can the Bible state that no human being should be present at the time of the High Priest’s service on Yom Kippur, when the High Priest himself was a human being? At least one man was present!

The Midrash answers that when the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies he was not human indeed; he assumed the status of a Heavenly Angel. Indeed, no human being entered the Sanctuary with him; not even his own.

What is going on here? We are confronted with an uneasy contradiction. One biblical source indicates the potential mind-staggering lowliness of a High Priest, capable of descending into the lowest depths of depraved behavior, while the other biblical source intimates his potential for enormous spiritual heights, capable of transcending the human experience and reaching angelic heights. How do we reconcile the two? Who is the High Priest, the holiest of the holy or the lowliest of the lowly?

Dust and image

Yet it is here we encounter, once again, Judaism’s moving perspective on the nature of the human being. There are two ways in which the Bible speaks of the creation of man. In the first chapter of Genesis, man is described as having been created in the image and likeness of G-d. In the second chapter, man is described as having been formed out of the dust of the earth. Together, image and dust express the polarity of the nature of man. He is formed of the most inferior stuff in the most superior image.

The author of life and of mankind knew full well that sexuality holds men -- priests and lay men alike -- captive in its enormously powerful grip. Even the greatest of men are capable of falling prey to its momentous temptation. Even a High Priest, on the holiest day of the year, in the holiest space of the world, while uttering the holiest word in the world, is capable of thinking grotesque thoughts about how he can "bump a man off the road" so that he can lay his hands on his woman. Judaism has always been keenly sensitive to the truth that every human being has a demon lurking within. If you don't challenge and tame it each day anew, it can turn you into a monster; you are capable of ugliness in the least expected circumstances.But the author of life also knew that the human person is capable of incredible greatness. The soul of man being a “fragment of G-d (8),” he or she is capable of generating infinite goodness and encountering within themselves infinite idealism. As Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel, a scion of the great Chassidic masters, once put it, “Man is a polarity of a divine image and worthless dust. He is a duality of mysterious grandeur and pompous aridity, a vision of G-d and a mountain of dust. It is because of his being dust that his iniquities may be forgiven, and it is because of his being an image that his holiness and idealism is expected.”

So, the next time you are overtaken by challenging cravings, addictions, temptations and any negative feelings, do not fall into despair. Remember, you are no worse than the High Priest of Israel! You, too, may struggle against horrible demons. But, you, too, may still enter into the Holy of Holies.

It is up to each of us to define who we are. The rest will become a self fulfilling prophesy.

1) Leviticus 21:7; 14. 2) See, for example, Sefer Hachenuch Parshas Emor; Mai Hasheluach vol. 2 Parshas Emor.

3) 1724-1806. The Chida, author of more than 50 volumes on Torah thought, was one of the great Torah luminaries of his day. He resided in Israel, Egypt and Italy. He quotes this interpretation in his book Penei David. The following explanation is also quoted in Moshav Zekanaim Al Hatorah (by the French 13th century authors of the Tosefot on the Talmud) in the name of “the Chassid.

Parenthetically, in an Emor essay by Rabbi Yissachar Frond he quotes Rabbi Bergman as stating that the above mentioned “Chassid” quoted in Moshav Zekanim refers to The Rokeach (this is the 13th century German mystic and sage, Rabbi Eliezer Rokeach). Yet, based on the explicit reference given by the Chida, I think the Moshav Zekanim is referring to Reb Yehudah Hachasid.

It should also be noted that the Chida himself rejects this interpretation in Penei David ibid.

4) Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid, who resided in Regensburg, Germany and authored the famed Sefer Chassidim, was known as one of the great kabbalists and Halachik authorities of his day.

5) This (according to one opinion in Midrash) is what Moses did when he wishes to kill the Egyptian who was beating a Jew (Exodus 2:14 and Midrash Tanchumah ibid. Quoted in Rashi ibid.) 6) Leviticus 16:17. 7) Midrash Rabah to Leviticus ibid. 8) Of course, not every High Priest was suspected of this. The ideal High Priest was a Tzaddik in the deepest sense of the word, whose challenges and struggles are of a different nature (see Tanya ch. 10 about the true definition of a tzaddik). Yet, throughout our history, there have been many High Priests of a lower caliber. 9) See Ramban to Genesis ch. 2; introduction to Shefa Tal (a 17th century major Kabbalistic work by Rabbi Shabsi Sheptel Horowitz); Tanya ch. 2.- Comment

Class Summary:

Why could the High Priest not marry a widow? A daring interpretation by Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid teaches us how Judaism views human nature: our proclivity to moral failure, coupled with our ability for transcendence.

Classes in this Series

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!

Shalom Alechem -4 years ago

Wanted to share an idea a friend had. I thought it was a brilliant point. It's a great point from the Chida that a Cohen can't marry a widow, and this point ALSO gives another reason why a divorcee is forbidden. If the Cohen knew a widow is prohibited, he could pray not for death, but for a divorce, and take the ex-wife that way.

- Thank you to my friend, who is actually a descendent of the Rambam, who had this chidish

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

moshe -5 years ago

Is it true that whereas Hashem created every creation, every creature, by His word alone, but only Man was created by a combination of (already created) dust and the Divine Breath?

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Jack Brian Bloom -7 years ago

Frankly, this is really not one of your best columns. You have to read the footnote to see that the Chida rejected this interpretation which is really illogical. The High Priest had to be married already in the first place and surely he would die if he had unholy thoughts at that time and that place. Why not just accept that he couldn't marry a widow because she wouldn't have been a virgin and because of her association with death?

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

levi -8 years ago

A humanitarian idea might be, that since so many Kohanim Gedolin died during their service on YK, the Torah would never want a widow to go through this pain again.

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.