Chabad Vs. Nietzsche

‘Love Thy Ego’ is at the Core of Torah. What the German Philosopher Didn’t Understand About Judaism

- January 26, 2012

- |

- 2 Sh'vat 5772

Rabbi YY Jacobson

2974 views

Chabad Vs. Nietzsche

‘Love Thy Ego’ is at the Core of Torah. What the German Philosopher Didn’t Understand About Judaism

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 26, 2012

Who’s Dead?

The following was seen on a wall in the subway:

"G-d is dead.”

—Nietzsche

"Nietzsche Is Dead.”

—G-d"Beggars should be abolished: it is irritating to give to them and it is irritating not to."—Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900).

“Come to Pharaoh”The opening of the 10th chapter of Exodus, the beginning of this week’s Torah portion (Bo) reads: "And G-d said to Moses: 'Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his servants in order that I might show My signs in their midst...'”

Two obvious questions come to mind: 1) Why does G-d tell Moses to “come to Pharaoh”? Would it not have been more appropriate to say, “Go to Pharaoh”? 2) The sentence “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart” is also difficult. What is the sequence? How does the fact that “I have hardened his heart” constitute the reason to “come to Pharaoh”? The Torah should have stated, “Come to Pharaoh and warn him.[1] I have hardened his heart so that I might show My signs.” The fact that G-d has hardened Pharaoh’s heart is not the reason to “come to Pharaoh.”The Torah, it seems, should have structured this sentence as it did earlier in Exodus, where G-d tells Moses: “You shall speak all that I command you, and Aaron, your brother, shall speak to Pharaoh, that he let the children of Israel out of his land. And I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and I will increase My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt. And Pharaoh will not listen to you, and I will lay My hand upon the Egyptians.”[2] Note: First G-d tells Moses and Aaron to speak to Pharaoh and instruct him to let the Jews go free; then G-d adds that He will harden Pharaoh’s heart. Here the message is different: “Come to Pharaoh because I have hardened his heart.” What is the meaning of this?

Moses’ Fear

The Zohar, the fundamental text of Kabbalah, presents a shocking answer to the first question.[3] Moses, the Zohar posits, was terrified to go to Pharaoh. G-d needed to promise him that He Himself would accompany him on this journey. “Go to Pharaoh,” would have not done the trick. Moses was too scared to go. “Come to Pharaoh” means “Come with Me to Pharaoh.” I will come with you to Pharaoh.

This begs for clarification. Moses has been to Pharaoh many times before. Why was he suddenly seized by fear?

The answer (alluded to in the Zohar) is that on earlier occasions, Moses met Pharaoh in other places, such as on the king’s morning excursions to the Nile.[4] This time, though, Moses was summoned to enter into Pharaoh’s innermost chamber, into the hub of his power.To quote the mystical words of the Zohar: “G-d summoned Moses into a chamber within a chamber, to the unique, supernal and mighty serpent… But Moses was afraid. Until this point, Moses had only approached the rivers surrounding the serpent (Pharaoh), and he was scared to approach the serpent itself, because Moses saw how profound its roots were on high!”[5]

The Zoharic “serpent” metaphor is based on a description of the prophet Ezekiel.[6] Ezekiel defined Pharaoh as “the great serpent who couches in the midst of his streams, who says: ‘My river is my own, and I have created myself.’” To enter into the center of power of this “great serpent,” the man with a mega-ego who insists “I have created myself,” terrified even Moses. How can you overcome a person who considers himself to be a god, the exclusive authority over his own life, the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong?For this, G-d told Moses two things: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” First, you are not going alone, you are coming with Me. Second, the reason you are really coming with Me is because “I have hardened his heart.” The very hardness of his heart is a reflection of Me.

Nietzsche's Understanding of Judaism

For this we must analyze the position of the ego within the Jewish tradition.

Conventional wisdom has it that the Jewish religion and its derivatives have declared a war on self-aggrandizement and the worship of self. Religion came to tame the ego and to cultivate a life of sacrifice and surrender. Occupation with the self and its needs and desires is selfish and brute and deprive one from the ultimate good of a relationship with G-d.

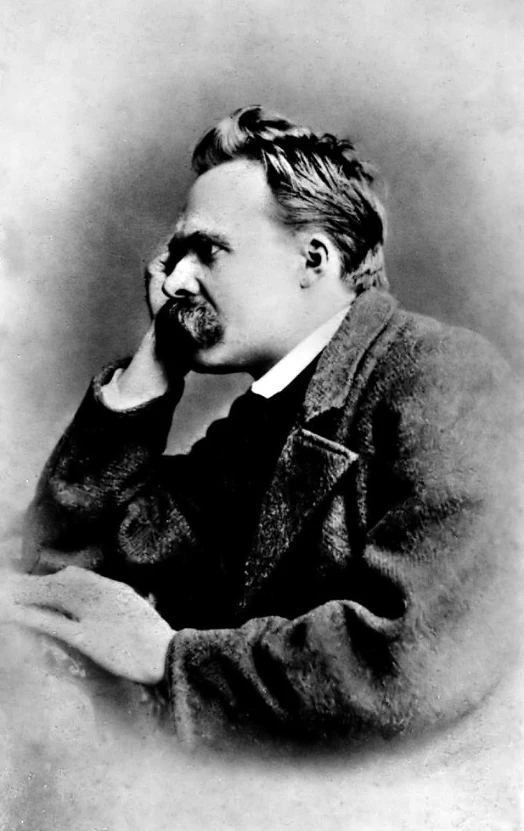

Among all philosophers, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), writing in the second half of the nineteenth century, captured this sentiment in brutal keenness. Nietzsche consistently opposed Judaism because Jews had given birth to Christianity, which to him represented the inversion of all natural instincts. Judaism found G-d in right, not might; in compassion, not ruthlessness; in humility, not aristocratic disdain. It represented all the things he despised: “pity, the kind and helping hand, the warm heart, patience, industriousness, humility, friendliness.” The true ethic was the precise opposite, the "Will To Power."

In "The Genealogy of Morals" the German philosopher wrote: “Whatever else has been done to damage the powerful and great of this earth seems trivial compared with what the Jews have done—that priestly people who succeeded in avenging themselves on their enemies and oppressors by radically inverting all their values, that is, by an act of the most spiritual vengeance.

“It was the Jew who, with frightening consistency, dared to invert the aristocratic value equations good/noble/powerful/beautiful/happy/favored-of-the-gods, and maintain, with the furious hatred of the underprivileged and impotent, that ‘only the poor, the powerless, are good; only the suffering, sick, and ugly, are truly blessed. But you noble and mighty ones of the earth will be, to all eternity, the evil, the cruel, the avaricious, the godless, and thus the cursed and damned.’

“It was the Jews who started the slave revolt in morals; a slave revolt with two millennia of history behind it, which we have lost sight of today simply because it has triumphed so completely.”

A War On Pity

In his book "The Antichrist" Nietzsche unleashed his tsunami-like fury against the G-d the Jews gave to the world and the “slave virtues” they invented:

“The god as the patron of the sick, the god as a spinner of cobwebs, the god as a spirit -- is one of the most corrupt concepts that has ever been set up in the world… God degenerated into the contradiction of life. In him war is declared on life, on nature, on the will to live! God becomes the formula for every slander upon the "here and now," and for every lie about the "beyond"! In him nothingness is deified, and the will to nothingness is made holy.

“The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world, for when they were confronted with the question, to be or not to be, they chose, with perfectly unearthly deliberation, to be at any price: this price involved a radical falsification of all nature, of all naturalness, of all reality, of the whole inner world, as well as of the outer. They put themselves against all those conditions under which, hitherto, a people had been able to live, or had even been permitted to live. Out of themselves they evolved an idea which stood in direct opposition to natural conditions—one by one they distorted religion, civilization, morality, history and psychology until each became a contradiction of its natural significance.

“Psychologically, the Jews are a people gifted with the very strongest vitality... The Jews are the very opposite of decadents: they have simply been forced into appearing in that guise, and with a degree of skill approaching the non plus ultra of histrionic genius they have managed to put themselves at the head of all decadent movements and so make of them something stronger than any party frankly saying Yes to life… The history of Israel is invaluable as a typical history of an attempt to de-naturize all natural values.”

The Contradiction

Nietzsche was aware of the contradiction inherent in his analysis of the Jews. On one hand “The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world,” professing extraordinary vigor, skill and genius, “the very strongest vitality.” Yet they chose to use their force and skill to embrace the slave virtues of weakness and defeat, rather than the master virtues of power and dominance. By their power and brilliance, Nietzsche believed, the Jews caused these destructive attributes to define civilization.

But how did this occur? Why would such a potentially successful people, capable of actualizing their “will for power,” embrace the path of mediocrity and extinction? Why would a nation with a healthy ego resort to a moral system that denies, rather than affirms, life? Why would a people capable of living by power embrace an invisible G-d who believes in the powerless and who denies the natural laws of life? Why didn't Judea become Rome, choosing the Master Morality over the Slave Morality?

Of course, Nietzsche was short sighted. He defines the good as that which enhances the feeling of life. If "to see others suffer does one good, then violence and cruelty may have to be granted the patent of morality and enlisted in the aesthete's palette of diversions." Yet, as scholars have pointed out,[7] attacks on virtue are most attractive when virtue remains well established, just as the homage to power, violence and cruelty seems amusingly bracing only so long as one doesn't suffer from them oneself. In 1887, such glorification of violence and the voluptuousness of victory and cruelty may have been intriguing and stimulating; by the 1930's, when the Nazis appropriated Nietzsche's rhetoric as a garland for their murderous deeds it had become impossible to view some of his passages without disgust.

It is no accident that seventy years after Nietzsche wrote about the "Death of G-d," referring to the end of the Judaic moral view on the world, his very own nation began exterminating the people of G-d.

Nietzsche never tired of pointing out that the demands of traditional morality fly in the face of life. The Jewish response to this claim was: Yes, and that is precisely why morality is so valuable: it acknowledges that man's allegiance is not only to life but also to what ennobles life, that, indeed, instinct and subjective desire themselves are not the highest court of appeals.

Nietzsche's heartlessness is reminiscent of Pharaoh's "stubborn heart" in the opening of this week's Torah portion. Both believed that to embrace compassion and sensitivity represented weakness. The goal of life was to become a barbarian. For the Jewish people, in contrast, creation was authored by a moral G-d who conceived the world in love. If G-d exists, then the moral law prevails, and there must be limits to power.

As it has been pointed out before, Nietzsche's conviction that morality ought to be defined by nature was also profoundly questionable. Did the philosopher not believe that people ought to live in homes and done clothing, to protect themselves against the furies of nature? Was curbing nature's forces desirable only when the subjective human being willed so?

Yet an important question remains: what did the Jewish people do with the "will for power" which according to Nietzsche runs supreme in man’s psyche? Did they ignore it, repress it or transcend it? What was the emotional and mental mechanism they employed in order to transform themselves from "masters" into "slaves"?

Setting the Stage for Change

The Talmud and the Kabbalah teaches that every historical ill is preceded by a force that is capable of vanquishing it.[8] Before a malady strikes the planet, the stage has already been set for its ultimate obliteration or transformation.

The same, I want to suggest, is true regarding Nietzsche’s powerful accusation against the Jews. Thirty-two years before Nietzsche’s birth in 1844, one of the greatest Jewish scholars and spiritual giants of his day penned a mystical discourse that would transform the landscape of Jewish thought and its perspective on the human will for power. This discourse claimed that in its profoundest interpretation, Judaism embraced rather than rejected the Ubermensch. Yet while Nietzsche’s Ubermensch represented the ideal of a being strong enough to create his own values, strong enough to live without the consolation of traditional morality, the Jewish Ubermensche, in its unbridled lust for power and self-affirmation, came to embrace the G-d of morality, justice and compassion. The Jews needed not to crush or deny their sense of selfhood and vitality in order to find G-d; on the contrary, the vibrant brute and selfish ego led them to G-d just as much—and maybe even more—as the call of transcendence and mystery that spoke to their souls.

The circumstances that brought about the penning of this discourse were extraordinary. It was December of 1812, and the author was escaping the French army who was swiftly advancing through Russia. Tragically, the cold Russian winter claimed the life of this saintly man, who passed away in a small town in the Ukraine called Piena. Two or three days before his passing (on the 24th of Teves 5573, December 27, 1812) he wrote this discourse, which can without exaggeration be described as one of the profoundest in the history of Jewish mysticism.

This man was Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), one of the great Jewish personalities of his day and the founder of the Chabad school of Kabbalah. This particular discourse was published posthumously in the fourth section of his famous magnum opus, the Tanya,[9] and subsequently explained by the six Chabad masters succeeding him.

Interestingly, the seventh leader of Chabad, the Lubavitcher Rebbe chose to address and explain this theme during the first Chassidic discourse he delivered upon assuming the leadership of Chabad in 1951.[10] This year, 2012, marks the beginning of the bicentennial since this discourse was written at the end of 1812.

One would expect that in a discourse written just prior to his death, a religious leader would discuss the meaninglessness of our false and temporary physical world, where G-d is eclipsed and the selfish ego reigns. Astonishingly, though, and contrary to the accepted notion of the function of religion, the author attributes the profoundest divinity to the egocentricity of human nature, to his will for power!

I am unaware of a similar document in Jewish thought, paying such profound tribute to the physical world of egotism and might. Perhaps this was the Rabbi Schnuer Zalman’s trailblazing response to the new world that existentialist philosophers the like of Nietzsche and the forces of emancipation and enlightenment were in the midst of creating. The Rebbe’s final essay attempted to present a deeper appreciation of Judaism, one that would become a necessity if Judaism was to thrive in the new milieu of individual freedom and unbridled self-expression.

The Genesis of Atheism

The question perturbing the religious thinker was from where we, the human race, inherited the potent will for power? From whence did we develop this sense of ego that is driven to banish G-d from our existence and to see ourselves as the axis of all reality, despite the inevitable angst and meaninglessness that might follow from this approach, what the Czech novelist Milan Kundera called "the unbearable lightness of being?"

For Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi, for whom the living presence of G-d was as real as physical existence itself if not more real, this was a burning question. From whence do we derive such a powerful sense of solitary individuality and selfish distinctiveness? From whence does the physical existence derive its brute immanence, its unyielding substantiality? How did the human being utterly dependent on G-d acquire a sense of self-containment that seeks to deny G-d all together?

If all existence comes from G-d, how was atheism born? How does G-d create a human imagination that denies its own very substance and reality?

The common religious answer for this is that atheism was born from G-d’s concealment in the universe. In Kabbalistic terminology this concealment is described as the “tzimtzum,” meaning G-d’s act of self-suspension that preceded the creation of an autonomous and self-contained universe. Rabbi Schnuer Zalman himself affirms this doctrine numerous times in his writings. Yet in the discourse that he chose to write as his final contribution to the world, he revealed a deeper truth. Atheism, he posits, did not originate in divine concealment, but rather in divine revelation.

Human spirituality, our sense of belonging, dependence and ego-less-ness are rooted not in the divine essence, but in the divine light. Hence, just as the divine light feels dependent and linked to its source, our spiritual side, too, feels dependent and linked to the cosmic consciousness. In contrast, the human physical sense of self, the crude ego and will for power, lacking any acknowledgement of anything outside of itself, is a reflection of the divine essence, of G-d’s innermost and intimate self. Therefore, it is absolutely self-contained, just as its progenitor.

The human ego, in other words, is nothing but the embodiment of the divine "ego." The human I mirrors the divine I. Just as the ultimate divine I has no antecedent, no preceding force that justifies its existence, no preexisting law to define it or curtail it, the human I, too, senses that its own self embodies the ultimate of existence, that its desires require no justification, its ambitions require no mitigation, and its power must reign supreme.

The Great Jewish Ego

So is the ego evil? Is this fundamental component of our existence an alien implant that must be uprooted and discarded in our quest for goodness and truth?

In the final analysis, it is not. The ego, the sense of self with which we are born, also derives from G-d; it is a reflection of the divine “ego.” We, who were created in G-d's image, possess an intimation of His “sense of self” in the form of our own concept of the self as the core of all existence.

It is not the ego that is evil, but the divorcing of the ego from its source. When we recognize our own ego as a reflection of G-d’s “ego,” it becomes the driving force in our efforts to make the world a better, more G-dly place. On the other hand, the same ego, severed from its divine moorings, begets the most monstrous of evils.

This is what Nietzsche failed to grasp and we, too, often fail to understand. The Jewish people did not embrace the “slave virtues” in spite of their master-like characteristics and capabilities. On the contrary, the Jews understood that for the great ego of man to be true to itself, to its essence, it must reflect its most authentic source: the divine intimate essence. Nietzsche himself always insisted that the most important thing is that people be true to themselves. The Jews understood that for the “will for power” to actualize itself in the profoundest way it must align itself with the divine. Its vigor must be directed toward constructing a G-dly world; its ambition must be harnessed toward the expulsion of cruelty and suffering and the building of a moral and loving civilization.

Confronting Pharaoh's Ego

When G-d commanded Moses to “Come to Pharaoh,” Moses had already been going to Pharaoh for many months. But he had been dealing with Pharaoh in his various manifestations: Pharaoh the pagan, Pharaoh the oppressor of Israel, Pharaoh the self-styled god. Now he was being told to enter into the essence of Pharaoh; he was to come face to face with a mega-ego that has no boundaries or constraints; he was to touch the raw, naked and infinite power of a man who declares that “I have created Myself.” Such power is ruthless, merciless, and limitless; nothing can contain it. It is the ultimate expression of human evil and it is frightening.Said G-d to Moses: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” Listen again to the words. It is I who have hardened his heart. The hardness of his heart—the unbridled mega ego of Pharaoh is really Me; it too comes from Me and expresses Me. If you have the courage to gaze beyond the very dense opaqueness of the human ego, you will find Me.

“Come with Me,” says G-d to Moses, and together we will enter the great serpent’s palace. Together we will penetrate the self-worship that is the heart of evil. Together we will discover that there is neither enduring substance nor eternal reality to Pharaoh's and Nietzsche's ego; that all it is, is the misappropriation of the divine in man.

If this truth is too terrifying for a human being to confront on his own, come with Me, and I will guide you. I will take you into the innermost chamber of Pharaoh’s soul, until you come face to face with evil’s most zealously guarded secret: that it does not, in truth, exist.

When you learn this secret, the great powers of history will never defeat you. Most importantly, when you learn this truth, you will be worthy to attain freedom. Liberty will become a force that instead of distancing you from the moral law and the divine will, will bring you closer to G-d. For you will have discovered the truth that your craving for individual self-expression and power is an embodiment of the most divine quality in your existence.

This explains the strange prophecy that the Moshiach (Messiah) will arrive as "a poor man riding on a donkey.”[11] The Hebrew word for donkey, chamor, can be translated as "brute materialism."[12] Moshiach riding on the donkey symbolizes the idea that Moshiach will reveal to the world that the brute forces behind materialism, in their deepest place, bespeak the truth of G-d as much—and even more—than the still, subtle voice of spiritual longing.[13]

[1] See Rashi to this verse, Exodus 10:1

[2] Exodus 7:2-4

[3] Zohar, part II, 34a

[4] See Exodus 7:15; 8:17

[5] Zohar, part II, 34a

[6] Ezekiel 29:3

[7] See "Nietzsche Still Influences," by Roger Kimball (United Press International, 2001)

[8] See, for example, Talmud Megilah 13b

[9] Tanya, Igeres Hakodesh section 20.

[10] Maamar Basi Legani 5710 (1950), published in Sefer Hamaamarim Melukat and in Sefer Hamaamarim Basi Legani vol. 1.

[11] Zecharyah 9:9

[12] See Gevuras Hashem by the Maharal of Progue chapter 29. Likkutei Sichos vol. 31 pp. 19-22.

[13] This essay is based on the Chassidic discourse Bo El Pharaoh of the year 5672, 1912, by Rabbi Sholom DovBer of Lubavitch, known as the Rebbe Rashab (published in Hemshech Taarab p. 832; 841, as well as on a number of talks by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, including his first address when he assumed leadership of the Chabad movement in 1951 (referenced in footnote #9). In it the Rebbe articulated what would become his approach of how to rebuild Judaism in a free and democratic society, in a generation often described as “the ME generation" (See Sichas Shabbos Shlach, 28 Sivan, 5789. Public Letter for Rosh Hashanah 5728, 1967, in the midst of the 60’s revolution.) The essay is also based on his address by the Rebbe of Shabbas Parshas Bo, 5752 (January 11, 1992), and particularly his address of Kislev 23, 5752 (November 30, 1991), both of them published in Sefer Hasichos 5752 vol.1, and Likkutei Sichos vol. 16, 24 Teves. Some sections of this essay were culled from "The Soul of Evil," by Rabbi Yanki Tauber. The connection to Nietzsche is my own.

- Comment

Class Summary:

Chabad Vs. Nietzsche - ‘Love Thy Ego’ is at the Core of Torah. What the German Philosopher Didn’t Understand About Judaism

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein- In the loving memory of: Alta Shula Swerdlov and in honor of Yetta Alta Shula, "Aliyah," Schottenstein

Who’s Dead?

The following was seen on a wall in the subway:

"G-d is dead.”

—Nietzsche

"Nietzsche Is Dead.”

—G-d

"Beggars should be abolished: it is irritating to give to them and it is irritating not to."—Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900).

“Come to Pharaoh”

The opening of the 10th chapter of Exodus, the beginning of this week’s Torah portion (Bo) reads: "And G-d said to Moses: 'Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his servants in order that I might show My signs in their midst...'”

Two obvious questions come to mind: 1) Why does G-d tell Moses to “come to Pharaoh”? Would it not have been more appropriate to say, “Go to Pharaoh”? 2) The sentence “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart” is also difficult. What is the sequence? How does the fact that “I have hardened his heart” constitute the reason to “come to Pharaoh”? The Torah should have stated, “Come to Pharaoh and warn him.[1] I have hardened his heart so that I might show My signs.” The fact that G-d has hardened Pharaoh’s heart is not the reason to “come to Pharaoh.”

The Torah, it seems, should have structured this sentence as it did earlier in Exodus, where G-d tells Moses: “You shall speak all that I command you, and Aaron, your brother, shall speak to Pharaoh, that he let the children of Israel out of his land. And I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and I will increase My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt. And Pharaoh will not listen to you, and I will lay My hand upon the Egyptians.”[2] Note: First G-d tells Moses and Aaron to speak to Pharaoh and instruct him to let the Jews go free; then G-d adds that He will harden Pharaoh’s heart. Here the message is different: “Come to Pharaoh because I have hardened his heart.” What is the meaning of this?

Moses’ Fear

The Zohar, the fundamental text of Kabbalah, presents a shocking answer to the first question.[3] Moses, the Zohar posits, was terrified to go to Pharaoh. G-d needed to promise him that He Himself would accompany him on this journey. “Go to Pharaoh,” would have not done the trick. Moses was too scared to go. “Come to Pharaoh” means “Come with Me to Pharaoh.” I will come with you to Pharaoh.

This begs for clarification. Moses has been to Pharaoh many times before. Why was he suddenly seized by fear?

The answer (alluded to in the Zohar) is that on earlier occasions, Moses met Pharaoh in other places, such as on the king’s morning excursions to the Nile.[4] This time, though, Moses was summoned to enter into Pharaoh’s innermost chamber, into the hub of his power.

To quote the mystical words of the Zohar: “G-d summoned Moses into a chamber within a chamber, to the unique, supernal and mighty serpent… But Moses was afraid. Until this point, Moses had only approached the rivers surrounding the serpent (Pharaoh), and he was scared to approach the serpent itself, because Moses saw how profound its roots were on high!”[5]

The Zoharic “serpent” metaphor is based on a description of the prophet Ezekiel.[6] Ezekiel defined Pharaoh as “the great serpent who couches in the midst of his streams, who says: ‘My river is my own, and I have created myself.’” To enter into the center of power of this “great serpent,” the man with a mega-ego who insists “I have created myself,” terrified even Moses. How can you overcome a person who considers himself to be a god, the exclusive authority over his own life, the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong?

For this, G-d told Moses two things: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” First, you are not going alone, you are coming with Me. Second, the reason you are really coming with Me is because “I have hardened his heart.” The very hardness of his heart is a reflection of Me.

Nietzsche's Understanding of Judaism

For this we must analyze the position of the ego within the Jewish tradition.

Conventional wisdom has it that the Jewish religion and its derivatives have declared a war on self-aggrandizement and the worship of self. Religion came to tame the ego and to cultivate a life of sacrifice and surrender. Occupation with the self and its needs and desires is selfish and brute and deprive one from the ultimate good of a relationship with G-d.

Among all philosophers, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), writing in the second half of the nineteenth century, captured this sentiment in brutal keenness. Nietzsche consistently opposed Judaism because Jews had given birth to Christianity, which to him represented the inversion of all natural instincts. Judaism found G-d in right, not might; in compassion, not ruthlessness; in humility, not aristocratic disdain. It represented all the things he despised: “pity, the kind and helping hand, the warm heart, patience, industriousness, humility, friendliness.” The true ethic was the precise opposite, the "Will To Power."

In "The Genealogy of Morals" the German philosopher wrote: “Whatever else has been done to damage the powerful and great of this earth seems trivial compared with what the Jews have done—that priestly people who succeeded in avenging themselves on their enemies and oppressors by radically inverting all their values, that is, by an act of the most spiritual vengeance.

“It was the Jew who, with frightening consistency, dared to invert the aristocratic value equations good/noble/powerful/beautiful/happy/favored-of-the-gods, and maintain, with the furious hatred of the underprivileged and impotent, that ‘only the poor, the powerless, are good; only the suffering, sick, and ugly, are truly blessed. But you noble and mighty ones of the earth will be, to all eternity, the evil, the cruel, the avaricious, the godless, and thus the cursed and damned.’

“It was the Jews who started the slave revolt in morals; a slave revolt with two millennia of history behind it, which we have lost sight of today simply because it has triumphed so completely.”

A War On Pity

In his book "The Antichrist" Nietzsche unleashed his tsunami-like fury against the G-d the Jews gave to the world and the “slave virtues” they invented:

“The god as the patron of the sick, the god as a spinner of cobwebs, the god as a spirit -- is one of the most corrupt concepts that has ever been set up in the world… God degenerated into the contradiction of life. In him war is declared on life, on nature, on the will to live! God becomes the formula for every slander upon the "here and now," and for every lie about the "beyond"! In him nothingness is deified, and the will to nothingness is made holy.

“The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world, for when they were confronted with the question, to be or not to be, they chose, with perfectly unearthly deliberation, to be at any price: this price involved a radical falsification of all nature, of all naturalness, of all reality, of the whole inner world, as well as of the outer. They put themselves against all those conditions under which, hitherto, a people had been able to live, or had even been permitted to live. Out of themselves they evolved an idea which stood in direct opposition to natural conditions—one by one they distorted religion, civilization, morality, history and psychology until each became a contradiction of its natural significance.

“Psychologically, the Jews are a people gifted with the very strongest vitality... The Jews are the very opposite of decadents: they have simply been forced into appearing in that guise, and with a degree of skill approaching the non plus ultra of histrionic genius they have managed to put themselves at the head of all decadent movements and so make of them something stronger than any party frankly saying Yes to life… The history of Israel is invaluable as a typical history of an attempt to de-naturize all natural values.”

The Contradiction

Nietzsche was aware of the contradiction inherent in his analysis of the Jews. On one hand “The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world,” professing extraordinary vigor, skill and genius, “the very strongest vitality.” Yet they chose to use their force and skill to embrace the slave virtues of weakness and defeat, rather than the master virtues of power and dominance. By their power and brilliance, Nietzsche believed, the Jews caused these destructive attributes to define civilization.

But how did this occur? Why would such a potentially successful people, capable of actualizing their “will for power,” embrace the path of mediocrity and extinction? Why would a nation with a healthy ego resort to a moral system that denies, rather than affirms, life? Why would a people capable of living by power embrace an invisible G-d who believes in the powerless and who denies the natural laws of life? Why didn't Judea become Rome, choosing the Master Morality over the Slave Morality?

Of course, Nietzsche was short sighted. He defines the good as that which enhances the feeling of life. If "to see others suffer does one good, then violence and cruelty may have to be granted the patent of morality and enlisted in the aesthete's palette of diversions." Yet, as scholars have pointed out,[7] attacks on virtue are most attractive when virtue remains well established, just as the homage to power, violence and cruelty seems amusingly bracing only so long as one doesn't suffer from them oneself. In 1887, such glorification of violence and the voluptuousness of victory and cruelty may have been intriguing and stimulating; by the 1930's, when the Nazis appropriated Nietzsche's rhetoric as a garland for their murderous deeds it had become impossible to view some of his passages without disgust.

It is no accident that seventy years after Nietzsche wrote about the "Death of G-d," referring to the end of the Judaic moral view on the world, his very own nation began exterminating the people of G-d.

Nietzsche never tired of pointing out that the demands of traditional morality fly in the face of life. The Jewish response to this claim was: Yes, and that is precisely why morality is so valuable: it acknowledges that man's allegiance is not only to life but also to what ennobles life, that, indeed, instinct and subjective desire themselves are not the highest court of appeals.

Nietzsche's heartlessness is reminiscent of Pharaoh's "stubborn heart" in the opening of this week's Torah portion. Both believed that to embrace compassion and sensitivity represented weakness. The goal of life was to become a barbarian. For the Jewish people, in contrast, creation was authored by a moral G-d who conceived the world in love. If G-d exists, then the moral law prevails, and there must be limits to power.

As it has been pointed out before, Nietzsche's conviction that morality ought to be defined by nature was also profoundly questionable. Did the philosopher not believe that people ought to live in homes and done clothing, to protect themselves against the furies of nature? Was curbing nature's forces desirable only when the subjective human being willed so?

Yet an important question remains: what did the Jewish people do with the "will for power" which according to Nietzsche runs supreme in man’s psyche? Did they ignore it, repress it or transcend it? What was the emotional and mental mechanism they employed in order to transform themselves from "masters" into "slaves"?

Setting the Stage for Change

The Talmud and the Kabbalah teaches that every historical ill is preceded by a force that is capable of vanquishing it.[8] Before a malady strikes the planet, the stage has already been set for its ultimate obliteration or transformation.

The same, I want to suggest, is true regarding Nietzsche’s powerful accusation against the Jews. Thirty-two years before Nietzsche’s birth in 1844, one of the greatest Jewish scholars and spiritual giants of his day penned a mystical discourse that would transform the landscape of Jewish thought and its perspective on the human will for power. This discourse claimed that in its profoundest interpretation, Judaism embraced rather than rejected the Ubermensch. Yet while Nietzsche’s Ubermensch represented the ideal of a being strong enough to create his own values, strong enough to live without the consolation of traditional morality, the Jewish Ubermensche, in its unbridled lust for power and self-affirmation, came to embrace the G-d of morality, justice and compassion. The Jews needed not to crush or deny their sense of selfhood and vitality in order to find G-d; on the contrary, the vibrant brute and selfish ego led them to G-d just as much—and maybe even more—as the call of transcendence and mystery that spoke to their souls.

The circumstances that brought about the penning of this discourse were extraordinary. It was December of 1812, and the author was escaping the French army who was swiftly advancing through Russia. Tragically, the cold Russian winter claimed the life of this saintly man, who passed away in a small town in the Ukraine called Piena. Two or three days before his passing (on the 24th of Teves 5573, December 27, 1812) he wrote this discourse, which can without exaggeration be described as one of the profoundest in the history of Jewish mysticism.

This man was Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), one of the great Jewish personalities of his day and the founder of the Chabad school of Kabbalah. This particular discourse was published posthumously in the fourth section of his famous magnum opus, the Tanya,[9] and subsequently explained by the six Chabad masters succeeding him.

Interestingly, the seventh leader of Chabad, the Lubavitcher Rebbe chose to address and explain this theme during the first Chassidic discourse he delivered upon assuming the leadership of Chabad in 1951.[10] This year, 2012, marks the beginning of the bicentennial since this discourse was written at the end of 1812.

One would expect that in a discourse written just prior to his death, a religious leader would discuss the meaninglessness of our false and temporary physical world, where G-d is eclipsed and the selfish ego reigns. Astonishingly, though, and contrary to the accepted notion of the function of religion, the author attributes the profoundest divinity to the egocentricity of human nature, to his will for power!

I am unaware of a similar document in Jewish thought, paying such profound tribute to the physical world of egotism and might. Perhaps this was the Rabbi Schnuer Zalman’s trailblazing response to the new world that existentialist philosophers the like of Nietzsche and the forces of emancipation and enlightenment were in the midst of creating. The Rebbe’s final essay attempted to present a deeper appreciation of Judaism, one that would become a necessity if Judaism was to thrive in the new milieu of individual freedom and unbridled self-expression.

The Genesis of Atheism

The question perturbing the religious thinker was from where we, the human race, inherited the potent will for power? From whence did we develop this sense of ego that is driven to banish G-d from our existence and to see ourselves as the axis of all reality, despite the inevitable angst and meaninglessness that might follow from this approach, what the Czech novelist Milan Kundera called "the unbearable lightness of being?"

For Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi, for whom the living presence of G-d was as real as physical existence itself if not more real, this was a burning question. From whence do we derive such a powerful sense of solitary individuality and selfish distinctiveness? From whence does the physical existence derive its brute immanence, its unyielding substantiality? How did the human being utterly dependent on G-d acquire a sense of self-containment that seeks to deny G-d all together?

If all existence comes from G-d, how was atheism born? How does G-d create a human imagination that denies its own very substance and reality?

The common religious answer for this is that atheism was born from G-d’s concealment in the universe. In Kabbalistic terminology this concealment is described as the “tzimtzum,” meaning G-d’s act of self-suspension that preceded the creation of an autonomous and self-contained universe. Rabbi Schnuer Zalman himself affirms this doctrine numerous times in his writings. Yet in the discourse that he chose to write as his final contribution to the world, he revealed a deeper truth. Atheism, he posits, did not originate in divine concealment, but rather in divine revelation.

Human spirituality, our sense of belonging, dependence and ego-less-ness are rooted not in the divine essence, but in the divine light. Hence, just as the divine light feels dependent and linked to its source, our spiritual side, too, feels dependent and linked to the cosmic consciousness. In contrast, the human physical sense of self, the crude ego and will for power, lacking any acknowledgement of anything outside of itself, is a reflection of the divine essence, of G-d’s innermost and intimate self. Therefore, it is absolutely self-contained, just as its progenitor.

The human ego, in other words, is nothing but the embodiment of the divine "ego." The human I mirrors the divine I. Just as the ultimate divine I has no antecedent, no preceding force that justifies its existence, no preexisting law to define it or curtail it, the human I, too, senses that its own self embodies the ultimate of existence, that its desires require no justification, its ambitions require no mitigation, and its power must reign supreme.

The Great Jewish Ego

So is the ego evil? Is this fundamental component of our existence an alien implant that must be uprooted and discarded in our quest for goodness and truth?

In the final analysis, it is not. The ego, the sense of self with which we are born, also derives from G-d; it is a reflection of the divine “ego.” We, who were created in G-d's image, possess an intimation of His “sense of self” in the form of our own concept of the self as the core of all existence.

It is not the ego that is evil, but the divorcing of the ego from its source. When we recognize our own ego as a reflection of G-d’s “ego,” it becomes the driving force in our efforts to make the world a better, more G-dly place. On the other hand, the same ego, severed from its divine moorings, begets the most monstrous of evils.

This is what Nietzsche failed to grasp and we, too, often fail to understand. The Jewish people did not embrace the “slave virtues” in spite of their master-like characteristics and capabilities. On the contrary, the Jews understood that for the great ego of man to be true to itself, to its essence, it must reflect its most authentic source: the divine intimate essence. Nietzsche himself always insisted that the most important thing is that people be true to themselves. The Jews understood that for the “will for power” to actualize itself in the profoundest way it must align itself with the divine. Its vigor must be directed toward constructing a G-dly world; its ambition must be harnessed toward the expulsion of cruelty and suffering and the building of a moral and loving civilization.

Confronting Pharaoh's Ego

When G-d commanded Moses to “Come to Pharaoh,” Moses had already been going to Pharaoh for many months. But he had been dealing with Pharaoh in his various manifestations: Pharaoh the pagan, Pharaoh the oppressor of Israel, Pharaoh the self-styled god. Now he was being told to enter into the essence of Pharaoh; he was to come face to face with a mega-ego that has no boundaries or constraints; he was to touch the raw, naked and infinite power of a man who declares that “I have created Myself.” Such power is ruthless, merciless, and limitless; nothing can contain it. It is the ultimate expression of human evil and it is frightening.

Said G-d to Moses: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” Listen again to the words. It is I who have hardened his heart. The hardness of his heart—the unbridled mega ego of Pharaoh is really Me; it too comes from Me and expresses Me. If you have the courage to gaze beyond the very dense opaqueness of the human ego, you will find Me.

“Come with Me,” says G-d to Moses, and together we will enter the great serpent’s palace. Together we will penetrate the self-worship that is the heart of evil. Together we will discover that there is neither enduring substance nor eternal reality to Pharaoh's and Nietzsche's ego; that all it is, is the misappropriation of the divine in man.

If this truth is too terrifying for a human being to confront on his own, come with Me, and I will guide you. I will take you into the innermost chamber of Pharaoh’s soul, until you come face to face with evil’s most zealously guarded secret: that it does not, in truth, exist.

When you learn this secret, the great powers of history will never defeat you. Most importantly, when you learn this truth, you will be worthy to attain freedom. Liberty will become a force that instead of distancing you from the moral law and the divine will, will bring you closer to G-d. For you will have discovered the truth that your craving for individual self-expression and power is an embodiment of the most divine quality in your existence.

This explains the strange prophecy that the Moshiach (Messiah) will arrive as "a poor man riding on a donkey.”[11] The Hebrew word for donkey, chamor, can be translated as "brute materialism."[12] Moshiach riding on the donkey symbolizes the idea that Moshiach will reveal to the world that the brute forces behind materialism, in their deepest place, bespeak the truth of G-d as much—and even more—than the still, subtle voice of spiritual longing.[13]

[1] See Rashi to this verse, Exodus 10:1

[2] Exodus 7:2-4

[3] Zohar, part II, 34a

[4] See Exodus 7:15; 8:17

[5] Zohar, part II, 34a

[6] Ezekiel 29:3

[7] See "Nietzsche Still Influences," by Roger Kimball (United Press International, 2001)

[8] See, for example, Talmud Megilah 13b

[9] Tanya, Igeres Hakodesh section 20.

[10] Maamar Basi Legani 5710 (1950), published in Sefer Hamaamarim Melukat and in Sefer Hamaamarim Basi Legani vol. 1.

[11] Zecharyah 9:9

[12] See Gevuras Hashem by the Maharal of Progue chapter 29. Likkutei Sichos vol. 31 pp. 19-22.

[13] This essay is based on the Chassidic discourse Bo El Pharaoh of the year 5672, 1912, by Rabbi Sholom DovBer of Lubavitch, known as the Rebbe Rashab (published in Hemshech Taarab p. 832; 841, as well as on a number of talks by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, including his first address when he assumed leadership of the Chabad movement in 1951 (referenced in footnote #9). In it the Rebbe articulated what would become his approach of how to rebuild Judaism in a free and democratic society, in a generation often described as “the ME generation" (See Sichas Shabbos Shlach, 28 Sivan, 5789. Public Letter for Rosh Hashanah 5728, 1967, in the midst of the 60’s revolution.) The essay is also based on his address by the Rebbe of Shabbas Parshas Bo, 5752 (January 11, 1992), and particularly his address of Kislev 23, 5752 (November 30, 1991), both of them published in Sefer Hasichos 5752 vol.1, and Likkutei Sichos vol. 16, 24 Teves. Some sections of this essay were culled from "The Soul of Evil," by Rabbi Yanki Tauber. The connection to Nietzsche is my own.

Tags

Categories

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 26, 2012

- |

- 2 Sh'vat 5772

- |

- 2974 views

Chabad Vs. Nietzsche

‘Love Thy Ego’ is at the Core of Torah. What the German Philosopher Didn’t Understand About Judaism

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 26, 2012

Who’s Dead?

The following was seen on a wall in the subway:

"G-d is dead.”

—Nietzsche

"Nietzsche Is Dead.”

—G-d"Beggars should be abolished: it is irritating to give to them and it is irritating not to."—Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900).

“Come to Pharaoh”The opening of the 10th chapter of Exodus, the beginning of this week’s Torah portion (Bo) reads: "And G-d said to Moses: 'Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his servants in order that I might show My signs in their midst...'”

Two obvious questions come to mind: 1) Why does G-d tell Moses to “come to Pharaoh”? Would it not have been more appropriate to say, “Go to Pharaoh”? 2) The sentence “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart” is also difficult. What is the sequence? How does the fact that “I have hardened his heart” constitute the reason to “come to Pharaoh”? The Torah should have stated, “Come to Pharaoh and warn him.[1] I have hardened his heart so that I might show My signs.” The fact that G-d has hardened Pharaoh’s heart is not the reason to “come to Pharaoh.”The Torah, it seems, should have structured this sentence as it did earlier in Exodus, where G-d tells Moses: “You shall speak all that I command you, and Aaron, your brother, shall speak to Pharaoh, that he let the children of Israel out of his land. And I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and I will increase My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt. And Pharaoh will not listen to you, and I will lay My hand upon the Egyptians.”[2] Note: First G-d tells Moses and Aaron to speak to Pharaoh and instruct him to let the Jews go free; then G-d adds that He will harden Pharaoh’s heart. Here the message is different: “Come to Pharaoh because I have hardened his heart.” What is the meaning of this?

Moses’ Fear

The Zohar, the fundamental text of Kabbalah, presents a shocking answer to the first question.[3] Moses, the Zohar posits, was terrified to go to Pharaoh. G-d needed to promise him that He Himself would accompany him on this journey. “Go to Pharaoh,” would have not done the trick. Moses was too scared to go. “Come to Pharaoh” means “Come with Me to Pharaoh.” I will come with you to Pharaoh.

This begs for clarification. Moses has been to Pharaoh many times before. Why was he suddenly seized by fear?

The answer (alluded to in the Zohar) is that on earlier occasions, Moses met Pharaoh in other places, such as on the king’s morning excursions to the Nile.[4] This time, though, Moses was summoned to enter into Pharaoh’s innermost chamber, into the hub of his power.To quote the mystical words of the Zohar: “G-d summoned Moses into a chamber within a chamber, to the unique, supernal and mighty serpent… But Moses was afraid. Until this point, Moses had only approached the rivers surrounding the serpent (Pharaoh), and he was scared to approach the serpent itself, because Moses saw how profound its roots were on high!”[5]

The Zoharic “serpent” metaphor is based on a description of the prophet Ezekiel.[6] Ezekiel defined Pharaoh as “the great serpent who couches in the midst of his streams, who says: ‘My river is my own, and I have created myself.’” To enter into the center of power of this “great serpent,” the man with a mega-ego who insists “I have created myself,” terrified even Moses. How can you overcome a person who considers himself to be a god, the exclusive authority over his own life, the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong?For this, G-d told Moses two things: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” First, you are not going alone, you are coming with Me. Second, the reason you are really coming with Me is because “I have hardened his heart.” The very hardness of his heart is a reflection of Me.

Nietzsche's Understanding of Judaism

For this we must analyze the position of the ego within the Jewish tradition.

Conventional wisdom has it that the Jewish religion and its derivatives have declared a war on self-aggrandizement and the worship of self. Religion came to tame the ego and to cultivate a life of sacrifice and surrender. Occupation with the self and its needs and desires is selfish and brute and deprive one from the ultimate good of a relationship with G-d.

Among all philosophers, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), writing in the second half of the nineteenth century, captured this sentiment in brutal keenness. Nietzsche consistently opposed Judaism because Jews had given birth to Christianity, which to him represented the inversion of all natural instincts. Judaism found G-d in right, not might; in compassion, not ruthlessness; in humility, not aristocratic disdain. It represented all the things he despised: “pity, the kind and helping hand, the warm heart, patience, industriousness, humility, friendliness.” The true ethic was the precise opposite, the "Will To Power."

In "The Genealogy of Morals" the German philosopher wrote: “Whatever else has been done to damage the powerful and great of this earth seems trivial compared with what the Jews have done—that priestly people who succeeded in avenging themselves on their enemies and oppressors by radically inverting all their values, that is, by an act of the most spiritual vengeance.

“It was the Jew who, with frightening consistency, dared to invert the aristocratic value equations good/noble/powerful/beautiful/happy/favored-of-the-gods, and maintain, with the furious hatred of the underprivileged and impotent, that ‘only the poor, the powerless, are good; only the suffering, sick, and ugly, are truly blessed. But you noble and mighty ones of the earth will be, to all eternity, the evil, the cruel, the avaricious, the godless, and thus the cursed and damned.’

“It was the Jews who started the slave revolt in morals; a slave revolt with two millennia of history behind it, which we have lost sight of today simply because it has triumphed so completely.”

A War On Pity

In his book "The Antichrist" Nietzsche unleashed his tsunami-like fury against the G-d the Jews gave to the world and the “slave virtues” they invented:

“The god as the patron of the sick, the god as a spinner of cobwebs, the god as a spirit -- is one of the most corrupt concepts that has ever been set up in the world… God degenerated into the contradiction of life. In him war is declared on life, on nature, on the will to live! God becomes the formula for every slander upon the "here and now," and for every lie about the "beyond"! In him nothingness is deified, and the will to nothingness is made holy.

“The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world, for when they were confronted with the question, to be or not to be, they chose, with perfectly unearthly deliberation, to be at any price: this price involved a radical falsification of all nature, of all naturalness, of all reality, of the whole inner world, as well as of the outer. They put themselves against all those conditions under which, hitherto, a people had been able to live, or had even been permitted to live. Out of themselves they evolved an idea which stood in direct opposition to natural conditions—one by one they distorted religion, civilization, morality, history and psychology until each became a contradiction of its natural significance.

“Psychologically, the Jews are a people gifted with the very strongest vitality... The Jews are the very opposite of decadents: they have simply been forced into appearing in that guise, and with a degree of skill approaching the non plus ultra of histrionic genius they have managed to put themselves at the head of all decadent movements and so make of them something stronger than any party frankly saying Yes to life… The history of Israel is invaluable as a typical history of an attempt to de-naturize all natural values.”

The Contradiction

Nietzsche was aware of the contradiction inherent in his analysis of the Jews. On one hand “The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world,” professing extraordinary vigor, skill and genius, “the very strongest vitality.” Yet they chose to use their force and skill to embrace the slave virtues of weakness and defeat, rather than the master virtues of power and dominance. By their power and brilliance, Nietzsche believed, the Jews caused these destructive attributes to define civilization.

But how did this occur? Why would such a potentially successful people, capable of actualizing their “will for power,” embrace the path of mediocrity and extinction? Why would a nation with a healthy ego resort to a moral system that denies, rather than affirms, life? Why would a people capable of living by power embrace an invisible G-d who believes in the powerless and who denies the natural laws of life? Why didn't Judea become Rome, choosing the Master Morality over the Slave Morality?

Of course, Nietzsche was short sighted. He defines the good as that which enhances the feeling of life. If "to see others suffer does one good, then violence and cruelty may have to be granted the patent of morality and enlisted in the aesthete's palette of diversions." Yet, as scholars have pointed out,[7] attacks on virtue are most attractive when virtue remains well established, just as the homage to power, violence and cruelty seems amusingly bracing only so long as one doesn't suffer from them oneself. In 1887, such glorification of violence and the voluptuousness of victory and cruelty may have been intriguing and stimulating; by the 1930's, when the Nazis appropriated Nietzsche's rhetoric as a garland for their murderous deeds it had become impossible to view some of his passages without disgust.

It is no accident that seventy years after Nietzsche wrote about the "Death of G-d," referring to the end of the Judaic moral view on the world, his very own nation began exterminating the people of G-d.

Nietzsche never tired of pointing out that the demands of traditional morality fly in the face of life. The Jewish response to this claim was: Yes, and that is precisely why morality is so valuable: it acknowledges that man's allegiance is not only to life but also to what ennobles life, that, indeed, instinct and subjective desire themselves are not the highest court of appeals.

Nietzsche's heartlessness is reminiscent of Pharaoh's "stubborn heart" in the opening of this week's Torah portion. Both believed that to embrace compassion and sensitivity represented weakness. The goal of life was to become a barbarian. For the Jewish people, in contrast, creation was authored by a moral G-d who conceived the world in love. If G-d exists, then the moral law prevails, and there must be limits to power.

As it has been pointed out before, Nietzsche's conviction that morality ought to be defined by nature was also profoundly questionable. Did the philosopher not believe that people ought to live in homes and done clothing, to protect themselves against the furies of nature? Was curbing nature's forces desirable only when the subjective human being willed so?

Yet an important question remains: what did the Jewish people do with the "will for power" which according to Nietzsche runs supreme in man’s psyche? Did they ignore it, repress it or transcend it? What was the emotional and mental mechanism they employed in order to transform themselves from "masters" into "slaves"?

Setting the Stage for Change

The Talmud and the Kabbalah teaches that every historical ill is preceded by a force that is capable of vanquishing it.[8] Before a malady strikes the planet, the stage has already been set for its ultimate obliteration or transformation.

The same, I want to suggest, is true regarding Nietzsche’s powerful accusation against the Jews. Thirty-two years before Nietzsche’s birth in 1844, one of the greatest Jewish scholars and spiritual giants of his day penned a mystical discourse that would transform the landscape of Jewish thought and its perspective on the human will for power. This discourse claimed that in its profoundest interpretation, Judaism embraced rather than rejected the Ubermensch. Yet while Nietzsche’s Ubermensch represented the ideal of a being strong enough to create his own values, strong enough to live without the consolation of traditional morality, the Jewish Ubermensche, in its unbridled lust for power and self-affirmation, came to embrace the G-d of morality, justice and compassion. The Jews needed not to crush or deny their sense of selfhood and vitality in order to find G-d; on the contrary, the vibrant brute and selfish ego led them to G-d just as much—and maybe even more—as the call of transcendence and mystery that spoke to their souls.

The circumstances that brought about the penning of this discourse were extraordinary. It was December of 1812, and the author was escaping the French army who was swiftly advancing through Russia. Tragically, the cold Russian winter claimed the life of this saintly man, who passed away in a small town in the Ukraine called Piena. Two or three days before his passing (on the 24th of Teves 5573, December 27, 1812) he wrote this discourse, which can without exaggeration be described as one of the profoundest in the history of Jewish mysticism.

This man was Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), one of the great Jewish personalities of his day and the founder of the Chabad school of Kabbalah. This particular discourse was published posthumously in the fourth section of his famous magnum opus, the Tanya,[9] and subsequently explained by the six Chabad masters succeeding him.

Interestingly, the seventh leader of Chabad, the Lubavitcher Rebbe chose to address and explain this theme during the first Chassidic discourse he delivered upon assuming the leadership of Chabad in 1951.[10] This year, 2012, marks the beginning of the bicentennial since this discourse was written at the end of 1812.

One would expect that in a discourse written just prior to his death, a religious leader would discuss the meaninglessness of our false and temporary physical world, where G-d is eclipsed and the selfish ego reigns. Astonishingly, though, and contrary to the accepted notion of the function of religion, the author attributes the profoundest divinity to the egocentricity of human nature, to his will for power!

I am unaware of a similar document in Jewish thought, paying such profound tribute to the physical world of egotism and might. Perhaps this was the Rabbi Schnuer Zalman’s trailblazing response to the new world that existentialist philosophers the like of Nietzsche and the forces of emancipation and enlightenment were in the midst of creating. The Rebbe’s final essay attempted to present a deeper appreciation of Judaism, one that would become a necessity if Judaism was to thrive in the new milieu of individual freedom and unbridled self-expression.

The Genesis of Atheism

The question perturbing the religious thinker was from where we, the human race, inherited the potent will for power? From whence did we develop this sense of ego that is driven to banish G-d from our existence and to see ourselves as the axis of all reality, despite the inevitable angst and meaninglessness that might follow from this approach, what the Czech novelist Milan Kundera called "the unbearable lightness of being?"

For Rabbi Schnuer Zalman of Liadi, for whom the living presence of G-d was as real as physical existence itself if not more real, this was a burning question. From whence do we derive such a powerful sense of solitary individuality and selfish distinctiveness? From whence does the physical existence derive its brute immanence, its unyielding substantiality? How did the human being utterly dependent on G-d acquire a sense of self-containment that seeks to deny G-d all together?

If all existence comes from G-d, how was atheism born? How does G-d create a human imagination that denies its own very substance and reality?

The common religious answer for this is that atheism was born from G-d’s concealment in the universe. In Kabbalistic terminology this concealment is described as the “tzimtzum,” meaning G-d’s act of self-suspension that preceded the creation of an autonomous and self-contained universe. Rabbi Schnuer Zalman himself affirms this doctrine numerous times in his writings. Yet in the discourse that he chose to write as his final contribution to the world, he revealed a deeper truth. Atheism, he posits, did not originate in divine concealment, but rather in divine revelation.

Human spirituality, our sense of belonging, dependence and ego-less-ness are rooted not in the divine essence, but in the divine light. Hence, just as the divine light feels dependent and linked to its source, our spiritual side, too, feels dependent and linked to the cosmic consciousness. In contrast, the human physical sense of self, the crude ego and will for power, lacking any acknowledgement of anything outside of itself, is a reflection of the divine essence, of G-d’s innermost and intimate self. Therefore, it is absolutely self-contained, just as its progenitor.

The human ego, in other words, is nothing but the embodiment of the divine "ego." The human I mirrors the divine I. Just as the ultimate divine I has no antecedent, no preceding force that justifies its existence, no preexisting law to define it or curtail it, the human I, too, senses that its own self embodies the ultimate of existence, that its desires require no justification, its ambitions require no mitigation, and its power must reign supreme.

The Great Jewish Ego

So is the ego evil? Is this fundamental component of our existence an alien implant that must be uprooted and discarded in our quest for goodness and truth?

In the final analysis, it is not. The ego, the sense of self with which we are born, also derives from G-d; it is a reflection of the divine “ego.” We, who were created in G-d's image, possess an intimation of His “sense of self” in the form of our own concept of the self as the core of all existence.

It is not the ego that is evil, but the divorcing of the ego from its source. When we recognize our own ego as a reflection of G-d’s “ego,” it becomes the driving force in our efforts to make the world a better, more G-dly place. On the other hand, the same ego, severed from its divine moorings, begets the most monstrous of evils.

This is what Nietzsche failed to grasp and we, too, often fail to understand. The Jewish people did not embrace the “slave virtues” in spite of their master-like characteristics and capabilities. On the contrary, the Jews understood that for the great ego of man to be true to itself, to its essence, it must reflect its most authentic source: the divine intimate essence. Nietzsche himself always insisted that the most important thing is that people be true to themselves. The Jews understood that for the “will for power” to actualize itself in the profoundest way it must align itself with the divine. Its vigor must be directed toward constructing a G-dly world; its ambition must be harnessed toward the expulsion of cruelty and suffering and the building of a moral and loving civilization.

Confronting Pharaoh's Ego

When G-d commanded Moses to “Come to Pharaoh,” Moses had already been going to Pharaoh for many months. But he had been dealing with Pharaoh in his various manifestations: Pharaoh the pagan, Pharaoh the oppressor of Israel, Pharaoh the self-styled god. Now he was being told to enter into the essence of Pharaoh; he was to come face to face with a mega-ego that has no boundaries or constraints; he was to touch the raw, naked and infinite power of a man who declares that “I have created Myself.” Such power is ruthless, merciless, and limitless; nothing can contain it. It is the ultimate expression of human evil and it is frightening.Said G-d to Moses: “Come to Pharaoh, because I have hardened his heart.” Listen again to the words. It is I who have hardened his heart. The hardness of his heart—the unbridled mega ego of Pharaoh is really Me; it too comes from Me and expresses Me. If you have the courage to gaze beyond the very dense opaqueness of the human ego, you will find Me.

“Come with Me,” says G-d to Moses, and together we will enter the great serpent’s palace. Together we will penetrate the self-worship that is the heart of evil. Together we will discover that there is neither enduring substance nor eternal reality to Pharaoh's and Nietzsche's ego; that all it is, is the misappropriation of the divine in man.

If this truth is too terrifying for a human being to confront on his own, come with Me, and I will guide you. I will take you into the innermost chamber of Pharaoh’s soul, until you come face to face with evil’s most zealously guarded secret: that it does not, in truth, exist.

When you learn this secret, the great powers of history will never defeat you. Most importantly, when you learn this truth, you will be worthy to attain freedom. Liberty will become a force that instead of distancing you from the moral law and the divine will, will bring you closer to G-d. For you will have discovered the truth that your craving for individual self-expression and power is an embodiment of the most divine quality in your existence.

This explains the strange prophecy that the Moshiach (Messiah) will arrive as "a poor man riding on a donkey.”[11] The Hebrew word for donkey, chamor, can be translated as "brute materialism."[12] Moshiach riding on the donkey symbolizes the idea that Moshiach will reveal to the world that the brute forces behind materialism, in their deepest place, bespeak the truth of G-d as much—and even more—than the still, subtle voice of spiritual longing.[13]

[1] See Rashi to this verse, Exodus 10:1

[2] Exodus 7:2-4

[3] Zohar, part II, 34a

[4] See Exodus 7:15; 8:17

[5] Zohar, part II, 34a

[6] Ezekiel 29:3

[7] See "Nietzsche Still Influences," by Roger Kimball (United Press International, 2001)

[8] See, for example, Talmud Megilah 13b

[9] Tanya, Igeres Hakodesh section 20.

[10] Maamar Basi Legani 5710 (1950), published in Sefer Hamaamarim Melukat and in Sefer Hamaamarim Basi Legani vol. 1.

[11] Zecharyah 9:9

[12] See Gevuras Hashem by the Maharal of Progue chapter 29. Likkutei Sichos vol. 31 pp. 19-22.

[13] This essay is based on the Chassidic discourse Bo El Pharaoh of the year 5672, 1912, by Rabbi Sholom DovBer of Lubavitch, known as the Rebbe Rashab (published in Hemshech Taarab p. 832; 841, as well as on a number of talks by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, including his first address when he assumed leadership of the Chabad movement in 1951 (referenced in footnote #9). In it the Rebbe articulated what would become his approach of how to rebuild Judaism in a free and democratic society, in a generation often described as “the ME generation" (See Sichas Shabbos Shlach, 28 Sivan, 5789. Public Letter for Rosh Hashanah 5728, 1967, in the midst of the 60’s revolution.) The essay is also based on his address by the Rebbe of Shabbas Parshas Bo, 5752 (January 11, 1992), and particularly his address of Kislev 23, 5752 (November 30, 1991), both of them published in Sefer Hasichos 5752 vol.1, and Likkutei Sichos vol. 16, 24 Teves. Some sections of this essay were culled from "The Soul of Evil," by Rabbi Yanki Tauber. The connection to Nietzsche is my own.

- Comment

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein- In the loving memory of: Alta Shula Swerdlov and in honor of Yetta Alta Shula, "Aliyah," Schottenstein

Class Summary:

Chabad Vs. Nietzsche - ‘Love Thy Ego’ is at the Core of Torah. What the German Philosopher Didn’t Understand About Judaism

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!