Sometimes, G-d Wants You Quarantined

Going Back to the Core

- March 20, 2020

- |

- 24 Adar 5780

Rabbi YY Jacobson

2130 views

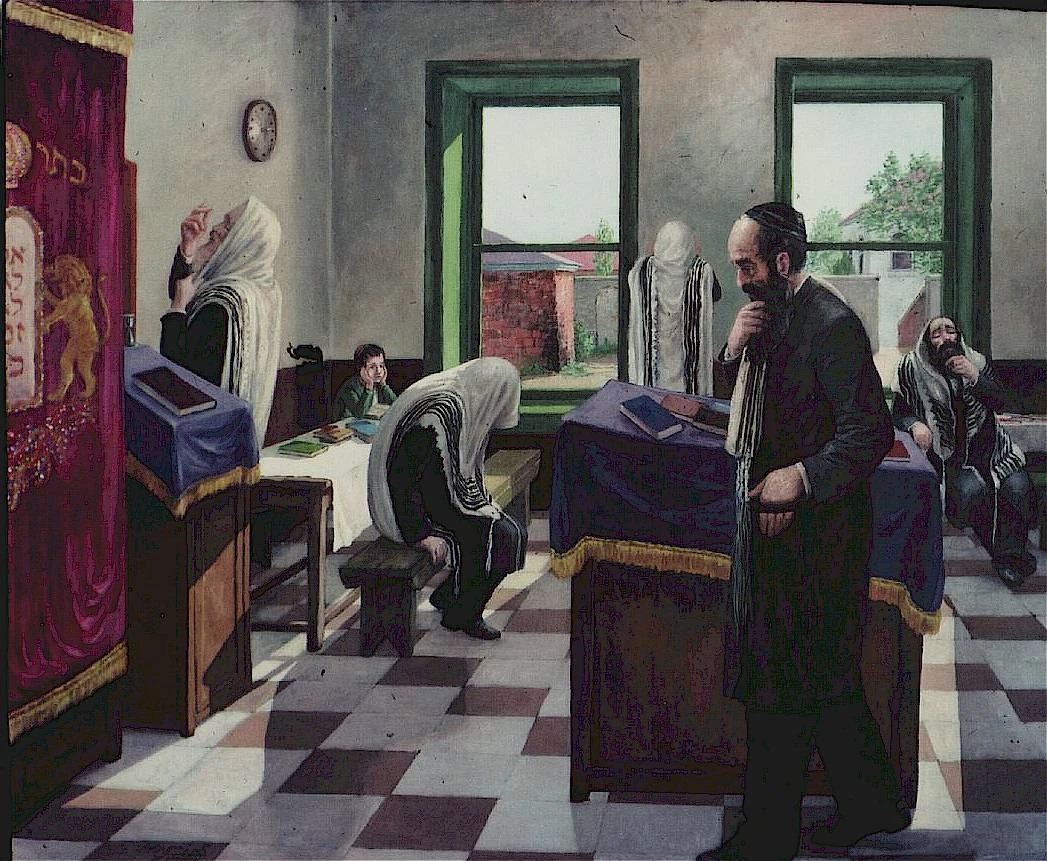

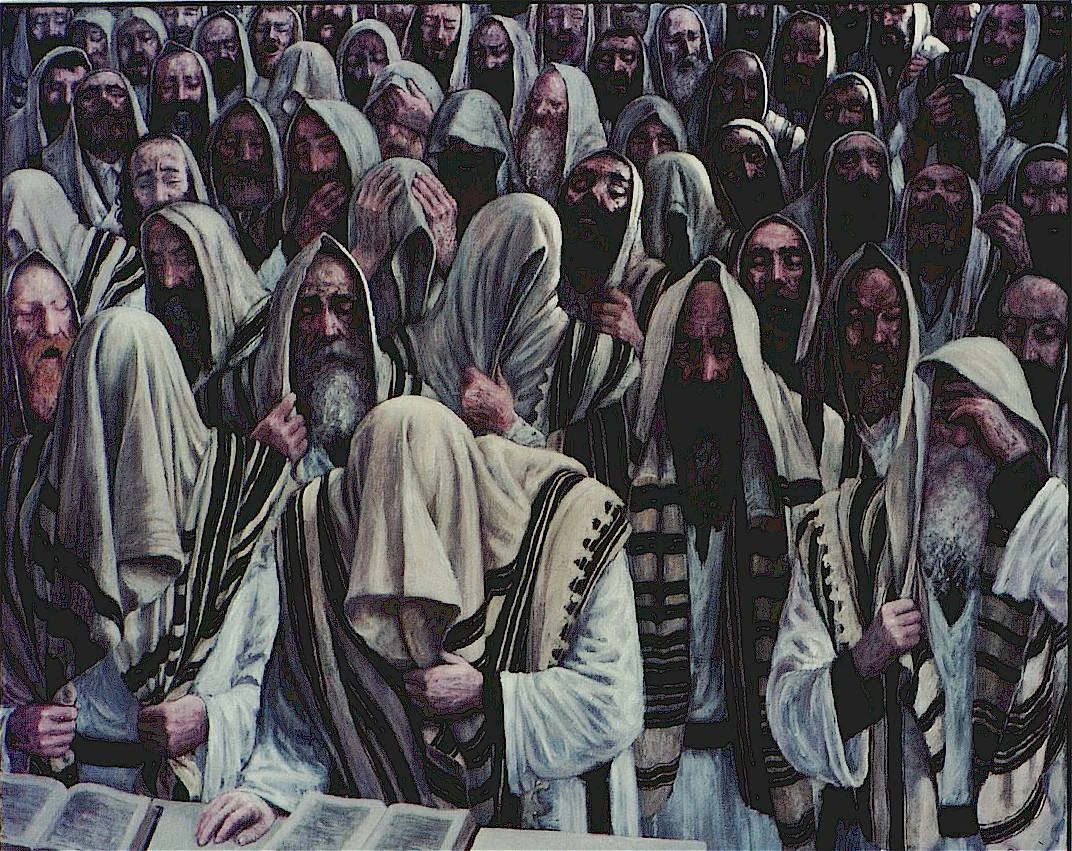

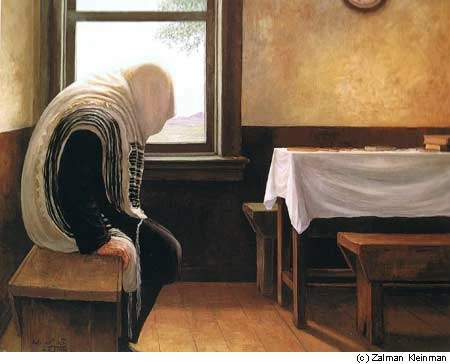

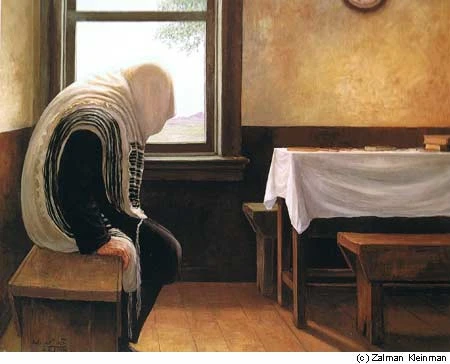

Painting by Zalman Kleinman

Sometimes, G-d Wants You Quarantined

Going Back to the Core

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 20, 2020

A New World

G-d caught almost everybody off guard. A tiny microorganism, the size of 125 nanometers, turned the world upside down. We are all quarantined in our homes.

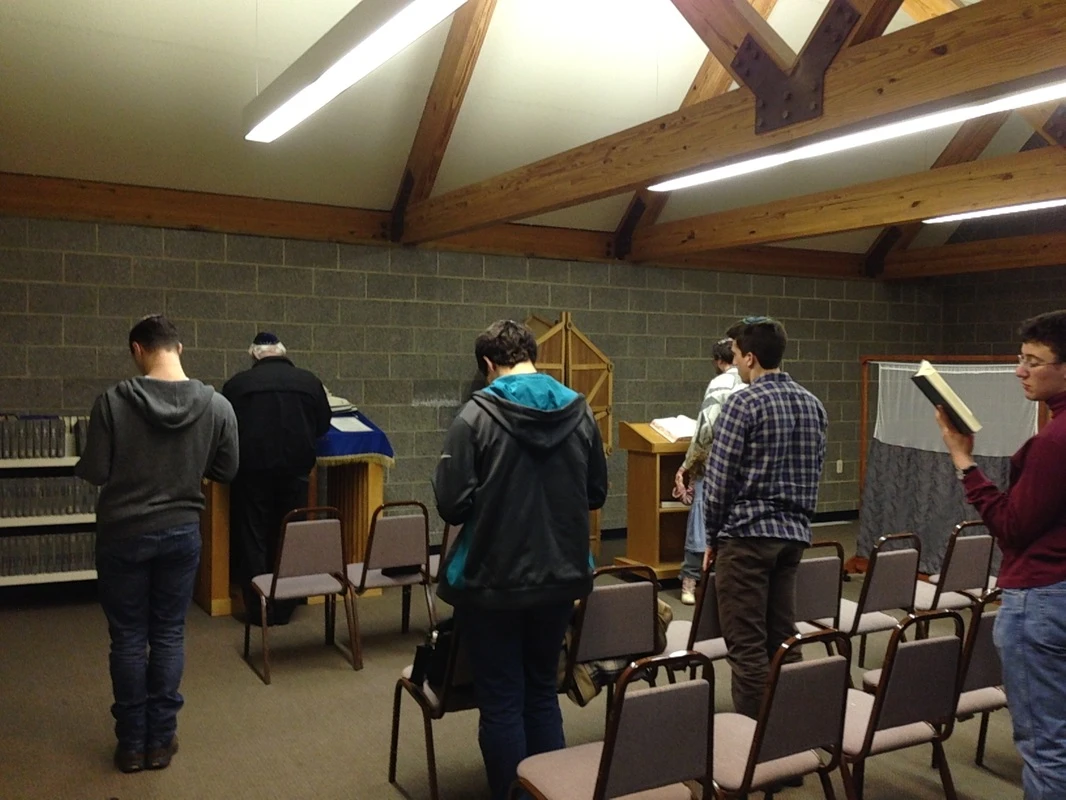

This Shabbos will be the first-time millions of us will not attend synagogue services and pray with our communities.

Here are two stories which inspire me today.

The Dirty Pail

The two saintly brothers, Reb Zusha and Reb Elimelech, who lived in 18th century Poland, wandered for years disguised as beggars, seeking to refine their characters and encourage their deprived brethren.

In one city, the two brothers, who later became mentors to many thousands of Jews, earned the wrath of a "real" beggar who informed the local police and had them cast into prison for the night. As they awoke in their prison cell, Reb Zusha noticed his brother weeping silently.

"Why do you cry?" asked Reb Zusha.

Reb Elimelech pointed to the pail situated in the corner of the room that inmates used for a toilet. "Jewish law forbids one to pray in a room inundated with such a repulsive odor," he told his brother. "This will be the first day in my life in which I will not have the opportunity to pray."

"And why are you upset about this?" asked Reb Zusha.

"What do you mean?" responded his brother. "How can I begin my day without connecting to G-d?"

"But you are connecting to G-d," insisted Reb Zusha. "The same G-d who commanded you to pray each morning, also commanded you to abstain from prayer under such circumstances, and with such an odor. In a location such as this, you connect to G-d by the absence of prayer.

“Your absence of prayer today is the will of G-d. today you connect to G-d through not praying…”

His brother's viewpoint elated Reb Elimelech's heart. The awareness that the waste-filled pail in the corner of the room allowed him the opportunity to enjoy an intimate—though different—type of relationship with G-d inspired him so deeply that he began to dance. The two brothers were now holding hands and dancing in celebration of their newly discovered relationship with their Father in heaven.

The non-Jewish inmates imprisoned in the same cell were so moved by the sight, that they soon joined the dance. It did not take long before the entire room was swept away by an electrifying energy of joy, as dozens of prisoners were dancing and jumping around ecstatically.

When the prison warden heard the commotion coming from the cell, he burst open the gate, only to be stunned by the inmates enjoying such a liberating dance. In his fury, the warden pulled aside one of the inmates, demanding from him an explanation for what was going on.

The frightened prisoner related that the outburst was not his fault, nor was it the fault of the other inmates. It was rather the two Jews dancing in the center of the circle who triggered the trouble.

"And what inspired the two Jews to go into such a dance?" thundered the warden.

The prisoner pointed to the pail in the corner of the room. "It is the pail, they claim, that brought about the joy in their heart."

“How can this smelly pail make them happy?”

“Well… they explained, that the pail allowed them to experience a new type of relationship with G-d. There was the pre-pail relationship… and the post-pail relationship… Somehow the pail transformed their spiritual perception.”

"If that's the case, I will teach them a lesson," shouted the angry warden. He took the pail and threw it out of the cell.

Reb Zusha turned to his brother and said: "And now, my brother, you can begin your prayers!"

This is the essence of Judaism. We are always in a relationship. G-d is with me at every moment. Sometimes He wants me to pray in shul; sometimes He wants me to pray at my home, with my heart, with my inner self, with my family.

And if this where I am meant to be, I will be here with my heart, soul, and al my vigor and joy.

Even when I am in a psychological dungeon, and there is a bucket of dirt around me, I am in a meaningful relationship with my soul and G-d. Each moment has an opportunity for growth, for discovery, for integrity.

Sometimes we build the relationship through prayer, sometimes through the absence of prayer. Sometimes we create the relationship by going outward and mingling; and sometimes, by being quarantined and going inward, spending time with ourselves and our closest kin. Sometimes we fulfill our mission by having lots of money and giving lots of charity; and sometimes by having less and giving according to our capabilities.

But the relationship is always intact.

In Siberia

Reb Mendel Futerfas was a Chabad Chassid, who spent 14 years in Soviet prisons and labor camps, due to his involvement in spreading Judaism in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

One night, in a barrack in ice-cold Siberia, the prisoners began talking about their lives BCE—Before the Communist Era, before Stalin turned daily life into a hellish nightmare in the Soviet Communist experiment, where bullets became substitutes for bread, and the gulag a replacement for having a job. Before he was arrested and exiled, one of the inmates was an actor, the other one—a writer, this one was a government official, the other one—a doctor, a clergy man, a novelist, a journalist, a successful business man, etc. Stalin sent to the Gulag the finest of Russian intelligentsia and kultur. If you thought for yourself, you were a threat to the Communist Party and could be either shot or exiled. Between 30 and 50 million people perished during Stalin’s 30 years of reign (from 1924 till 1953).

As the men were sitting in the barrack, recalling their wonderful, even glorious pasts, they broke down sobbing. “Once upon a time, we had everything; today we have nothing. Once upon a time, we had a sense of self, identity, worth; today everything has been taken from us.”

Only one man in the barrack was not crying. This was the Chabad Chassid, Reb Mendel. He was listening intently to the tales of woe delivered by the inmates but was not weeping with them.

“I guess you were a loser then, so you lost nothing now!” exclaimed one inmate. “If you got nothing, you got nothing to lose…”

“Actually,” Reb Mendel said, “I had a very successful business, which I lost. I also was married with children and I miss my family so deeply.”

“So why don’t you weep with us? Don’t you feel that your very sense of self-worth has been snatched from you be these animals?”

“I do feel tremendous sadness and pain,” responded the Chassid. “I miss my wife, I miss my children, I miss my freedom. I miss having a home and a bed to sleep in, and some extra bread in my pantry. I am concerned for my future. But I must tell you that my primary occupation I did not lose, not even here in Siberia.

“You see, before I was arrested and exiled, I ran a large business, I earned lots of money, but that did not constitute the essence of my identity, it did not define the mission of my life, it did not capture the ultimate meaning of my existence. My primary occupation was that I was a servant of G-d. I awoke each morning remembering that my life was given to me as a gift in order to serve G-d one more day.

“And this primary occupation of mine they could not take away from me in Siberia. Here too I serve G-d each and every day. The only difference is in the software, not in the hardware. Previously I served G-d as a successful businessman; today I serve G-d here as a Siberian prisoner!”

Reb Mendel articulated the secret of the Jew and the secret of inner dignity. He defined himself not by what he had, but by what he was. He was a Jew. He was a servant of G-d; he was an agent of the Divine on earth. In a way, even in Siberia he was a free man. Even in Siberia, he was still one, wholesome, confident, anchored, and centered.

Sometimes G-d wants me to serve Him in the midst of people; sometimes He wants me to serve Him as a quarantined soul.

The Jewish people always understood that you need to have an epicenter, an inner unshakable core that cannot go down with the fluctuations and vicissitudes of life. That core is made up not by our external realities and circumstances, but of our moral integrity, our connectedness to G-d; it is comprised of our love, loyalty, faith, and the intimacy we share with our soul and our Creator.

- Comment

Class Summary:

Going Back to the Core

Dedicated by Abe Spitz

A New World

G-d caught almost everybody off guard. A tiny microorganism, the size of 125 nanometers, turned the world upside down. We are all quarantined in our homes.

This Shabbos will be the first-time millions of us will not attend synagogue services and pray with our communities.

Here are two stories which inspire me today.

The Dirty Pail

The two saintly brothers, Reb Zusha and Reb Elimelech, who lived in 18th century Poland, wandered for years disguised as beggars, seeking to refine their characters and encourage their deprived brethren.

In one city, the two brothers, who later became mentors to many thousands of Jews, earned the wrath of a "real" beggar who informed the local police and had them cast into prison for the night. As they awoke in their prison cell, Reb Zusha noticed his brother weeping silently.

"Why do you cry?" asked Reb Zusha.

Reb Elimelech pointed to the pail situated in the corner of the room that inmates used for a toilet. "Jewish law forbids one to pray in a room inundated with such a repulsive odor," he told his brother. "This will be the first day in my life in which I will not have the opportunity to pray."

"And why are you upset about this?" asked Reb Zusha.

"What do you mean?" responded his brother. "How can I begin my day without connecting to G-d?"

"But you are connecting to G-d," insisted Reb Zusha. "The same G-d who commanded you to pray each morning, also commanded you to abstain from prayer under such circumstances, and with such an odor. In a location such as this, you connect to G-d by the absence of prayer.

“Your absence of prayer today is the will of G-d. today you connect to G-d through not praying…”

His brother's viewpoint elated Reb Elimelech's heart. The awareness that the waste-filled pail in the corner of the room allowed him the opportunity to enjoy an intimate—though different—type of relationship with G-d inspired him so deeply that he began to dance. The two brothers were now holding hands and dancing in celebration of their newly discovered relationship with their Father in heaven.

The non-Jewish inmates imprisoned in the same cell were so moved by the sight, that they soon joined the dance. It did not take long before the entire room was swept away by an electrifying energy of joy, as dozens of prisoners were dancing and jumping around ecstatically.

When the prison warden heard the commotion coming from the cell, he burst open the gate, only to be stunned by the inmates enjoying such a liberating dance. In his fury, the warden pulled aside one of the inmates, demanding from him an explanation for what was going on.

The frightened prisoner related that the outburst was not his fault, nor was it the fault of the other inmates. It was rather the two Jews dancing in the center of the circle who triggered the trouble.

"And what inspired the two Jews to go into such a dance?" thundered the warden.

The prisoner pointed to the pail in the corner of the room. "It is the pail, they claim, that brought about the joy in their heart."

“How can this smelly pail make them happy?”

“Well… they explained, that the pail allowed them to experience a new type of relationship with G-d. There was the pre-pail relationship… and the post-pail relationship… Somehow the pail transformed their spiritual perception.”

"If that's the case, I will teach them a lesson," shouted the angry warden. He took the pail and threw it out of the cell.

Reb Zusha turned to his brother and said: "And now, my brother, you can begin your prayers!"

This is the essence of Judaism. We are always in a relationship. G-d is with me at every moment. Sometimes He wants me to pray in shul; sometimes He wants me to pray at my home, with my heart, with my inner self, with my family.

And if this where I am meant to be, I will be here with my heart, soul, and al my vigor and joy.

Even when I am in a psychological dungeon, and there is a bucket of dirt around me, I am in a meaningful relationship with my soul and G-d. Each moment has an opportunity for growth, for discovery, for integrity.

Sometimes we build the relationship through prayer, sometimes through the absence of prayer. Sometimes we create the relationship by going outward and mingling; and sometimes, by being quarantined and going inward, spending time with ourselves and our closest kin. Sometimes we fulfill our mission by having lots of money and giving lots of charity; and sometimes by having less and giving according to our capabilities.

But the relationship is always intact.

In Siberia

Reb Mendel Futerfas was a Chabad Chassid, who spent 14 years in Soviet prisons and labor camps, due to his involvement in spreading Judaism in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

One night, in a barrack in ice-cold Siberia, the prisoners began talking about their lives BCE—Before the Communist Era, before Stalin turned daily life into a hellish nightmare in the Soviet Communist experiment, where bullets became substitutes for bread, and the gulag a replacement for having a job. Before he was arrested and exiled, one of the inmates was an actor, the other one—a writer, this one was a government official, the other one—a doctor, a clergy man, a novelist, a journalist, a successful business man, etc. Stalin sent to the Gulag the finest of Russian intelligentsia and kultur. If you thought for yourself, you were a threat to the Communist Party and could be either shot or exiled. Between 30 and 50 million people perished during Stalin’s 30 years of reign (from 1924 till 1953).

As the men were sitting in the barrack, recalling their wonderful, even glorious pasts, they broke down sobbing. “Once upon a time, we had everything; today we have nothing. Once upon a time, we had a sense of self, identity, worth; today everything has been taken from us.”

Only one man in the barrack was not crying. This was the Chabad Chassid, Reb Mendel. He was listening intently to the tales of woe delivered by the inmates but was not weeping with them.

“I guess you were a loser then, so you lost nothing now!” exclaimed one inmate. “If you got nothing, you got nothing to lose…”

“Actually,” Reb Mendel said, “I had a very successful business, which I lost. I also was married with children and I miss my family so deeply.”

“So why don’t you weep with us? Don’t you feel that your very sense of self-worth has been snatched from you be these animals?”

“I do feel tremendous sadness and pain,” responded the Chassid. “I miss my wife, I miss my children, I miss my freedom. I miss having a home and a bed to sleep in, and some extra bread in my pantry. I am concerned for my future. But I must tell you that my primary occupation I did not lose, not even here in Siberia.

“You see, before I was arrested and exiled, I ran a large business, I earned lots of money, but that did not constitute the essence of my identity, it did not define the mission of my life, it did not capture the ultimate meaning of my existence. My primary occupation was that I was a servant of G-d. I awoke each morning remembering that my life was given to me as a gift in order to serve G-d one more day.

“And this primary occupation of mine they could not take away from me in Siberia. Here too I serve G-d each and every day. The only difference is in the software, not in the hardware. Previously I served G-d as a successful businessman; today I serve G-d here as a Siberian prisoner!”

Reb Mendel articulated the secret of the Jew and the secret of inner dignity. He defined himself not by what he had, but by what he was. He was a Jew. He was a servant of G-d; he was an agent of the Divine on earth. In a way, even in Siberia he was a free man. Even in Siberia, he was still one, wholesome, confident, anchored, and centered.

Sometimes G-d wants me to serve Him in the midst of people; sometimes He wants me to serve Him as a quarantined soul.

The Jewish people always understood that you need to have an epicenter, an inner unshakable core that cannot go down with the fluctuations and vicissitudes of life. That core is made up not by our external realities and circumstances, but of our moral integrity, our connectedness to G-d; it is comprised of our love, loyalty, faith, and the intimacy we share with our soul and our Creator.

Tags

Categories

A Perspective on the Coronavirus Quarantine

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 20, 2020

- |

- 24 Adar 5780

- |

- 2130 views

Sometimes, G-d Wants You Quarantined

Going Back to the Core

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 20, 2020

A New World

G-d caught almost everybody off guard. A tiny microorganism, the size of 125 nanometers, turned the world upside down. We are all quarantined in our homes.

This Shabbos will be the first-time millions of us will not attend synagogue services and pray with our communities.

Here are two stories which inspire me today.

The Dirty Pail

The two saintly brothers, Reb Zusha and Reb Elimelech, who lived in 18th century Poland, wandered for years disguised as beggars, seeking to refine their characters and encourage their deprived brethren.

In one city, the two brothers, who later became mentors to many thousands of Jews, earned the wrath of a "real" beggar who informed the local police and had them cast into prison for the night. As they awoke in their prison cell, Reb Zusha noticed his brother weeping silently.

"Why do you cry?" asked Reb Zusha.

Reb Elimelech pointed to the pail situated in the corner of the room that inmates used for a toilet. "Jewish law forbids one to pray in a room inundated with such a repulsive odor," he told his brother. "This will be the first day in my life in which I will not have the opportunity to pray."

"And why are you upset about this?" asked Reb Zusha.

"What do you mean?" responded his brother. "How can I begin my day without connecting to G-d?"

"But you are connecting to G-d," insisted Reb Zusha. "The same G-d who commanded you to pray each morning, also commanded you to abstain from prayer under such circumstances, and with such an odor. In a location such as this, you connect to G-d by the absence of prayer.

“Your absence of prayer today is the will of G-d. today you connect to G-d through not praying…”

His brother's viewpoint elated Reb Elimelech's heart. The awareness that the waste-filled pail in the corner of the room allowed him the opportunity to enjoy an intimate—though different—type of relationship with G-d inspired him so deeply that he began to dance. The two brothers were now holding hands and dancing in celebration of their newly discovered relationship with their Father in heaven.

The non-Jewish inmates imprisoned in the same cell were so moved by the sight, that they soon joined the dance. It did not take long before the entire room was swept away by an electrifying energy of joy, as dozens of prisoners were dancing and jumping around ecstatically.

When the prison warden heard the commotion coming from the cell, he burst open the gate, only to be stunned by the inmates enjoying such a liberating dance. In his fury, the warden pulled aside one of the inmates, demanding from him an explanation for what was going on.

The frightened prisoner related that the outburst was not his fault, nor was it the fault of the other inmates. It was rather the two Jews dancing in the center of the circle who triggered the trouble.

"And what inspired the two Jews to go into such a dance?" thundered the warden.

The prisoner pointed to the pail in the corner of the room. "It is the pail, they claim, that brought about the joy in their heart."

“How can this smelly pail make them happy?”

“Well… they explained, that the pail allowed them to experience a new type of relationship with G-d. There was the pre-pail relationship… and the post-pail relationship… Somehow the pail transformed their spiritual perception.”

"If that's the case, I will teach them a lesson," shouted the angry warden. He took the pail and threw it out of the cell.

Reb Zusha turned to his brother and said: "And now, my brother, you can begin your prayers!"

This is the essence of Judaism. We are always in a relationship. G-d is with me at every moment. Sometimes He wants me to pray in shul; sometimes He wants me to pray at my home, with my heart, with my inner self, with my family.

And if this where I am meant to be, I will be here with my heart, soul, and al my vigor and joy.

Even when I am in a psychological dungeon, and there is a bucket of dirt around me, I am in a meaningful relationship with my soul and G-d. Each moment has an opportunity for growth, for discovery, for integrity.

Sometimes we build the relationship through prayer, sometimes through the absence of prayer. Sometimes we create the relationship by going outward and mingling; and sometimes, by being quarantined and going inward, spending time with ourselves and our closest kin. Sometimes we fulfill our mission by having lots of money and giving lots of charity; and sometimes by having less and giving according to our capabilities.

But the relationship is always intact.

In Siberia

Reb Mendel Futerfas was a Chabad Chassid, who spent 14 years in Soviet prisons and labor camps, due to his involvement in spreading Judaism in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

One night, in a barrack in ice-cold Siberia, the prisoners began talking about their lives BCE—Before the Communist Era, before Stalin turned daily life into a hellish nightmare in the Soviet Communist experiment, where bullets became substitutes for bread, and the gulag a replacement for having a job. Before he was arrested and exiled, one of the inmates was an actor, the other one—a writer, this one was a government official, the other one—a doctor, a clergy man, a novelist, a journalist, a successful business man, etc. Stalin sent to the Gulag the finest of Russian intelligentsia and kultur. If you thought for yourself, you were a threat to the Communist Party and could be either shot or exiled. Between 30 and 50 million people perished during Stalin’s 30 years of reign (from 1924 till 1953).

As the men were sitting in the barrack, recalling their wonderful, even glorious pasts, they broke down sobbing. “Once upon a time, we had everything; today we have nothing. Once upon a time, we had a sense of self, identity, worth; today everything has been taken from us.”

Only one man in the barrack was not crying. This was the Chabad Chassid, Reb Mendel. He was listening intently to the tales of woe delivered by the inmates but was not weeping with them.

“I guess you were a loser then, so you lost nothing now!” exclaimed one inmate. “If you got nothing, you got nothing to lose…”

“Actually,” Reb Mendel said, “I had a very successful business, which I lost. I also was married with children and I miss my family so deeply.”

“So why don’t you weep with us? Don’t you feel that your very sense of self-worth has been snatched from you be these animals?”

“I do feel tremendous sadness and pain,” responded the Chassid. “I miss my wife, I miss my children, I miss my freedom. I miss having a home and a bed to sleep in, and some extra bread in my pantry. I am concerned for my future. But I must tell you that my primary occupation I did not lose, not even here in Siberia.

“You see, before I was arrested and exiled, I ran a large business, I earned lots of money, but that did not constitute the essence of my identity, it did not define the mission of my life, it did not capture the ultimate meaning of my existence. My primary occupation was that I was a servant of G-d. I awoke each morning remembering that my life was given to me as a gift in order to serve G-d one more day.

“And this primary occupation of mine they could not take away from me in Siberia. Here too I serve G-d each and every day. The only difference is in the software, not in the hardware. Previously I served G-d as a successful businessman; today I serve G-d here as a Siberian prisoner!”

Reb Mendel articulated the secret of the Jew and the secret of inner dignity. He defined himself not by what he had, but by what he was. He was a Jew. He was a servant of G-d; he was an agent of the Divine on earth. In a way, even in Siberia he was a free man. Even in Siberia, he was still one, wholesome, confident, anchored, and centered.

Sometimes G-d wants me to serve Him in the midst of people; sometimes He wants me to serve Him as a quarantined soul.

The Jewish people always understood that you need to have an epicenter, an inner unshakable core that cannot go down with the fluctuations and vicissitudes of life. That core is made up not by our external realities and circumstances, but of our moral integrity, our connectedness to G-d; it is comprised of our love, loyalty, faith, and the intimacy we share with our soul and our Creator.

- Comment

Dedicated by Abe Spitz

Class Summary:

Going Back to the Core

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!

Ari -2 years ago

And Moshiach now!

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Ari -2 years ago

Amen! These are amazing stories.

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Chaim -4 years ago

How can you compare ......

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Marvin -4 years ago

Dear Rabbi Jacobson

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Sara -4 years ago

This message really and truly was the best I have heard since the pandemic. Thank you so much

Sarah

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

YEHUDA L KLEIN -4 years ago

I suggest that you pass the word to our friends at Ohr Chaim. They seem to be an outlier -- all other shuls have done the right thing and shut down. They are already know as a breeding ground for the virus and this is clearly not a Kiddush Hashem.

Keep healthy and safe,

Yehuda Klein

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Sheldon Steinlauf -4 years ago

The sky is not falling. Pass it on

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Anonymous -4 years ago

Only a blind eye can't see the works of God, named CoronaVirus. Our history tells us the story of the MERAGLIM, where they lied about Israel.. the MERAGLIM were high positioned rabbi's. Unfortunately most rabbanim never said or say the truth! God d

God doesn't change!

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Miriam Rhodes -4 years ago

miriam rhodes

bravo!

sending warm blessings from bat ayin

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

Rifka Saltz -4 years ago

Dear Rabbi Jacobson,

Well said. In other words we have to accept Hashem’s will for us now, serving him from where we find ourselves. We’re not supposed to think of our separateness as as a reason to not serve G-d. It’s as though Hashem changed the rulebook. Davenning with a minyan - no. Daven alone.

Plus in the quiet and lack of activity of this Shabbos, we might gain insights into what G-d wants fromus, as a tsibur and as individuals.

Thank you for opening our eyes to this extraordinary time we find ourselves in.

have a great Shabbos

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.