A Jewish Heart, Spine, Eye and Mouth

How the Four Species Reflect the Lives of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph

- October 3, 2017

- |

- 13 Tishrei 5778

Rabbi YY Jacobson

9 views

A Jewish Heart, Spine, Eye and Mouth

How the Four Species Reflect the Lives of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2017

My Daily Regimen

My doctor took one look at my gut and refused to believe that I work out. So I listed the exercises I do every day: jump to conclusions, climb the walls, drag my heels, push my luck, make mountains out of molehills, bend over backward, run around in circles, put my foot in my mouth, go over the edge, and beat around the bush.

The Psychiatrist

At psychiatrist:

- Do you consume alcohol?

- No.

- Do you smoke?

- No.

- Do you use drugs?

- No.

- Do you play cards?

- No.

- Do you run after other women?

- No.

- So why did you come to me?

- You see, doc, I have one little problem - I lie a lot...

The Four Species

Comes Sukkos, and Jews the world over become expert botanists, suddenly gaining impeccable tastes in the growth, health, and beauty of a citron fruit, a palm branch, a myrtle and a willow. These are the four species which Jews around the world have spent exorbitant amounts of money to buy what they perceived to be the best and most perfect of these four species. We hold on to these four types for the seven days of Sukkos, we shake them every day, and we treat them like little princesses.

It comes straight from Leviticus:

אמור כג, מ: וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי נָחַל וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים.

And you shall take for yourselves on the first day, the splendid tree-fruit, date palm fronds, a branch of a braided tree, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your G-d for a seven day period.

But why these four?

Do you know how many plants there are in the world? The total number of plant species in the world is estimated at 390,900 by the Royal Botanic Gardens. Approximately 1,000 to 2,000 species of plants are edible by humans. About 100 to 200 species of plants play an important role in world commerce, and about 15 species provide the majority of food crops. (These include soybeans, peanuts, rice, wheat and bananas.)

There are estimated to be about 7500 types of just apples and 1600 types of bananas alone. To put that in perspective, if you ate a new type of apple each day, it would take you a little over twenty years to try them all. For the bananas, it's a little over four years.

So the obvious question is, why does the Torah choose from among 390,000 pants to take these four species on Sukkos? The citrus, palm branch, myrtle, and willow. They are not even edible fruits and plants!

Four Persons

Over millennia, scores of insights have been offered. Two of them (among others) are quoted in the Midrash, and they both seem strange.

ויקרא רבה ל, י: "פרי עץ הדר" - זה אברהם, שהדרו הקדוש ברוך הוא בשיבה טובה, שנאמר (בראשית כד, א): "ואברהם זקן בא בימים", וכתיב (ויקרא יט, לב): "והדרת פני זקן", "כפות תמרים" - זה יצחק, שהיה כפות ועקוד על גבי המזבח. "וענף עץ עבות" - זה יעקב, מה הדס זה רחוש בעלין כך היה יעקב רחוש בבנים. "וערבי נחל" - זה יוסף, מה ערבה זו כמושה לפני ג' מינין הללו כך מת יוסף לפני אחיו.

The Midrash explains that these four species represents our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph. The “beautiful fruit” represents Abraham, beautified by old age. “And Abraham grew old; he came in his days,” Genesis says.

The palm branch combining all the leaves and binding them together [The Torah writes, “fronds of dates,” but the word kapot (“fronds of”) also means “bound,” implying that we are to take a closed frond, the heart of the palm], reminds of us of Isaac who was bound on the altar.

Jacob had many children just as the myrtle branch is full of leaves. Joseph died before his brother just as the willow withers before the other three plants.

This begs for an explanation. The connection between these four types of plants and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and Joseph appears like a stretch. Also, why do we want to remind ourselves on Sukkos of these particular four people? Furthermore, must we use plants to recall them?

Four Organs

A few lines later, the Midrash gives us another insight:

ויקרא רבה ל, יד: יד רבי מני פתח (תהלים לה, י): "כל עצמותי תאמרנה ה' מי כמוך" לא נאמר פסוק זה אלא בשביל לולב. השדרה של לולב דומה לשדרה של אדם. וההדס דומה לעין. וערבה דומה לפה. והאתרוג דומה ללב. אמר דוד אין בכל האיברים גדול מאלו שהן שקולין כנגד כל הגוף הוי "כל עצמותי תאמרנה":

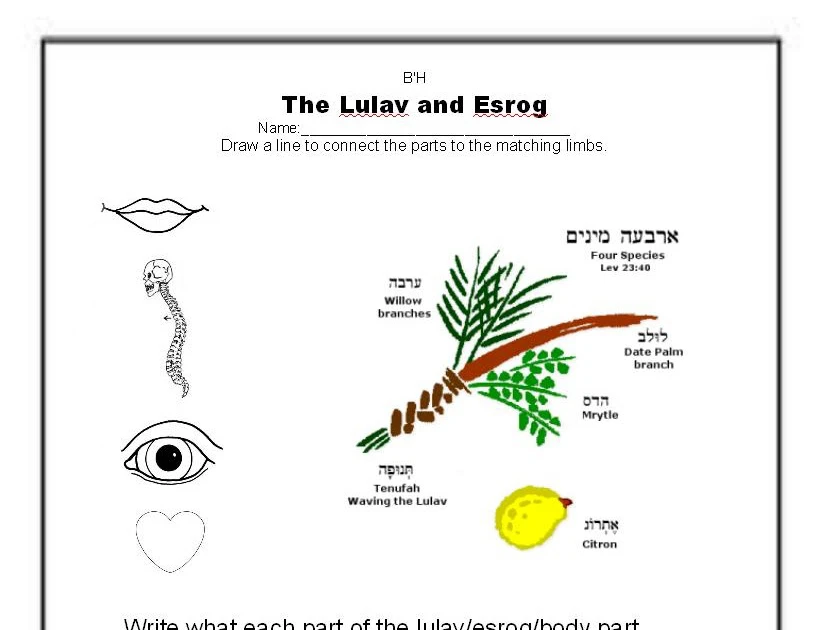

The four plants reflect four major parts of the human body. (Demonstrate to your crowd, by lifting up each type and perhaps a large image of a heart, spine, eye and mouth). The citrus looks like the heart. The Lulav mirrors the human spine. The hadas leaf is shaped like an eye. The willow leaf is shaped like a mouth.

This is charming. But here too we must ask, why are trying to recall these four parts of our body?

Perhaps, the two explanations in the Midrash are interrelated. On Sukkos we are invited to “take to ourselves” the heart, spine, eye and mouth. But of whom? Of Abaraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. On this holiday we are charged with the mission to embracing the Esrog—the heart of Abraham; the Lulav—the spine of Isaac; the Hadas—the eyes of Jacob; and Arravah—the mouth of Joseph.[1]

The Jewish Heart

The heart of Abraham represents the legendary and timeless “Jewish heart.”

A Jew walked in to a shul in New York in 1949. No one knew him. No one owed him anything. A complete stranger. But people walked over to him: Sholom Aleichem! Where are you from? Do you have where to stay? Do you have where to eat? Which city you come from? Ah! You knew my uncle. Which camp did you survive? How did you make it out of here? You need help finding a job? Did you maybe meet anyone of my family in the D.P. camps?

And a Jew walks in to a shul in 2017. The questions may be different, but the heart—the heart of Abraham, the heart filled with sensitivity, love to mankind—is the same. The same Jewish heart, the heart of the man who had a tent with four doors, on all sides, to welcome guests from all directions—still beats in our organisms 3600 years later.

“Chesed L’Avraham,” the prophet says. Kindness belongs to Abraham. This was the “hadar,” the beauty and splendor he was blessed with.

The Function of a Heart

Rabbi Moshe Tzur, an Israeli Air Force veteran, now lives with his family in Jerusalem, Israel. After his service in the Air Force, he went on to found a number of yeshivos.

He related this story.

In 1969, when I was serving in the Israeli Air Force – during the hard times in the aftermath of the Six Day War, when soldiers did not have much food to eat – I remember a jeep pulling up and someone handing me a package. A note on the package said, “Purim Samayach mehaRebbe miLubavitch – Happy Purim from the Lubavitcher Rebbe.”

I remember wondering, as did every soldier who got the same package, “Who is this Rebbe of Lubavitch? Why does he care so much about us to deliver sweets to us in the middle of the desert?” I must say I was touched and impressed.

In 1971, I was sent to the Suez Canal to bring back wounded soldiers to the hospital in the north. I did this day after day, and it was really very difficult to see so many gravely wounded. One day, my convoy came across two Chabad people who asked us to put teffilin on. I did, and when I recited the Shema prayer – “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is one” – I became very emotional and started crying. From that moment began my journey of return to Judaism.

When I finished my military service, I came to New York and I met the Rebbe.

In one of my meetings with the Rebbe he asked me what I was doing for the Jewish community. And he spoke to me about the commandment to love your neighbor as yourself.

As the conversation got more intense and involved, the Rebbe finally turned to me and said:

I have a question. Which is the most important limb after the brain?

“The heart.”

And which is the more important side in Judaism? Right or left?

For sure the right. Joseph is upset when his father places his left hand on the oldest son. The right is associated with more love, closeness, and vigor.

So, asked the Rebbe, why is the heart on the left side of the body? Everything important in Judaism is on the right side. We put on tefillin with the right hand, we put the mezuzah on the right side of the door, we shake hands with the right hand, we hold the Torah scroll on our right side, in the Temple they always waked to the right, so why is the heart—the organ responsible for our blood and vitality—is on the left?”

The man remained silent.

I will tell you the answer, said the Rebbe. The heart is really to the right, not to the left.

You see, the heart of a person is made to feel, to emphasize with, to connect, to be there for another person, for another Jew. My heart was given to me to feel your pain, your needs, and your concerns. My heart was given to me to experience the soul and the heart of the person standing in front of me. My heart is here for you. And from your vantage point, my heart is on your right!…

When you face another Jew, your heart is opposite his right side. For your heart beats not for you but for the other, for the fellow whom you must love as yourself.

This message really spoke to me, and I adopted it as the center of my philosophy of life. And, since then, my mission in life has been to reach the heart of every Jew that I meet.

After succeeding in business in Chicago, I returned to Israel, and I established two important yeshivot. One yeshiva is called Aish HaTalmud; it is a yeshiva high school with almost two hundred boys enrolled. The other is called Torat Moshe, with about ninety-five boys. I have also established four kollelim, study groups for married men, with almost a hundred-twenty enrolled.

I also founded an organization to support poor families for Rosh Hashanah and Passover. These are people who don’t have much income, and we help them with food and money.

All this because of the words of the Rebbe – that the key is to help others – which changed my perspective on life and shaped my life’s mission.

A Scroll on Mt. Herzl

It all happened on a simple day back in 2011.[2] A group of 50 Jewish teenagers visited Israel in a program known as “Write on For Israel,” in which these youngsters spend a few intense weeks learning much of the history and the reality of Israel, as a training program for them to become spokesmen for Israel at their future schools and campuses.

As their visit was coming to an end, just a few hours before their flight back home to the US, the kids visited Mt. Herzl, gazing at the thousands of graves of Israeli soldiers killed in battle over the last seven decades.

Suddenly they noticed a mom and dad standing at a grave, weeping silently. One of the boys approached them, introduced himself, and inquired about the person buried in the grave.

They said it was their son Erez. Erez Deri, the son of Penina and Gidon Deri, was killed in 2006 following an operation in Jenin. He went in to Jenin, the center for dispatching suicide bombers to murder as many Jews as possible, to take on the killers. His tank turned over and he was killed.

Erez’s mother said:

“Our dream was to bring Erez to the chupah… to watch him get married and begin a family. But in 2006, our dream was shattered. Our family has been devastated as a result of this tragedy.

“Last night, Erez came to me in a dream. He said: Mother! We bring our children into chupah. But there is one more thing we “bring in to the chupah:” A Torah Scroll. When we complete writing a Torah, we lead it under a chupah, just like a groom and bride, and we bring it in to a shul, singing and dancing, just like a wedding.

“You can’t bring me into marriage. But you know what? Why not write a Torah in my name and you will bring that it to a chupah—it will be like marrying me off!”

And the mother continues: I awoke from the dream. But we are a simple family, not wealthy. We are also a secular family, and do not know much about writing a Torah Scroll. I do not even know where to begin. How do I write a Torah for my son Erez? So I came to here to my son’s grave to pray…”

The teenager approached the director of their group, Rabbi Yutav Eliach, and asked him one question:

How much does it cost to write a new Torah?

$35,000. Or, 130,000 Shekel, he said.

The teenager shared the story with the entire group. They all decided right there at Mt. Herzl to donate the Torah for Erez.

They did the math. If each of the 50 students gave or raised $700 it would cover the entire project.

Many of them stuck their hands into their pockets and gave Rabbi Yutav the $700. The others pledged to deliver him the money they would raise upon their return to the US.

A few month later, a surreal scene took place in Maale Adumim, a town close to Jerusalem, where Erez’s family lives. It was Sunday, March 4, 2012. With music blasting, 50 New York-area teens from Write On For Israel, danced up the streets of this West Bank community with a Sefer Torah they brought from the United States. The Torah was donated to a local synagogue in memory of one of its young members, fallen IDF soldier Erez Deri.

The 50 students fulfilled the promise made to Deri’s parents following a chance meeting at Mount Herzl a few months earlier.

“We started as strangers and returned as extended members of the Deri family,” said Daniella Greenbaum, leader of the fundraising effort. “It was beyond exciting to see the joy that we brought to these parents and to affirm the idea that we are all members of Am Yisrael, responsible for one another.”

At the celebration, Penina Erez, said to the students: I feel the presence of Erez at this celebration. I feel like I brought my child into the chupah! I feel like he is dancing with us. A terrible burden has been lifted from our family.

A few months later, the family celebrated the wedding of one of Erez’s brothers.

This is the embodiment of the Jewish heart—the Esrog. The heart of Abraham. A heart that feels the pain, the needs, the plight and the soul of another human being.

The Spine

The Lulav represents the “Jewish spine.” This is the spine and sense of confidence and pride represented by Isaac who with an upright posture walked to the altar and allowed himself, like the fronds of the palm, to be bound. As Abraham tells him that G-d chose him as an offering, the Torah states, “they walked together.” Isaac continues to walk upright. He does not duck, bend, or run.

Isaac bequeathed that “spine,” the Lulav, to us—the ability for us to make sacrifices for truth, for G-d, for Yiddishkeit, with vigor, pride, dignity and unwavering resolve. We need not apologize for being Jewish, and become defensive, meek, bent, or repressed. We carry our Jewishness with full confidence and dignity. We stand erect. We are capable of standing up for our people and our faith with pride and full stature.

A King in Dachau

Rabbi Yosef Wallis living today in Israel related the following story he heard from his father. For me, it captures the image of a Jew who even in the hell of hells never forfeits his spine, his Lulav; he sees himself as a King. Even in a place where they stripped you from every notion of value, this man did not duck.

While his father, Judah, was in the Dachau concentration camp, a Jew who was being taken to his death suddenly flung a small bag at Judah Wallis. He caught it, thinking it might contain a piece of bread. Upon opening it, however, he discovered a pair of tefilin (the phylacteries donned each morning by Jewish men). Judah was very frightened because he knew that were he to be caught carrying tefillin, he would be put to death instantly. So he hid the tefillin under his shirt and headed for his bunkhouse.

In the morning, just before the roll call, while still in his bunkhouse, he would put on the tefillin. One morning, unexpectedly, a German officer appeared. He ordered him to remove the tefillin, noted the number on Judah’s arm, and ordered him to go straight to the roll call.

At the roll call, in front of thousands of silent Jews, the officer called out Judah’s number and he had no choice but to step forward. The German officer waved the tefillin in the air and screamed, “Dog! I sentence you to death by public hanging for wearing these!”

Judah was placed on a stool and a noose was placed around his neck. Before he was hanged, the officer said in a mocking tone, “Dog, what is your last wish?” “To wear my tefillin one last time,” Judah replied.

The SS officer was dumbfounded. He handed Judah the tefillin. As Judah put them on, he recited the incredibly moving verse from the prophet Hosea that many Jews say while winding the tefillin around the fingers: “Ve’eirastich li le’olam, ve’eirastich li b’tzedek ub’mishpat, ub’chessed, ub’rachamim, ve’eirastich li b’emunah, v’yodaat es Hashem;” I will betroth you to Me forever and I will betroth you to Me with righteousness, and with justice, and with kindness, and with mercy, and I will betroth you to Me with loyalty, and you shall know G-d.

In silence, the entire camped looked on at the Jew with a noose around his neck, and tefillin on his head and arm, awaiting his death for the ‘crime’ of observing this mitzvah. Even women from the adjoining camp were lined up at the barbed wire fence that separated them from the men’s camp, compelled to watch this ominous sight.

As Judah turned to the silent crowd, he saw tears in many people’s eyes. Even at that moment, as he was about to be hanged, he was shocked: Jews were crying! How was it possible that they still had tears left to shed? And for a stranger? Where were those tears coming from? Impulsively, in Yiddish, he called out, “Yidden, don’t cry. With tefillin on, I am the victor! Don’t you understand? The victory is mine!”

The German officer understood the Yiddish and was infuriated. He said to Judah, “You dog, you think you are the victor? Hanging is too good for you. You are going to get another kind of death.”

Judah was taken from the stool, and the noose was removed from his neck. He was forced into a squatting position and two large rocks were placed under his armpits. Then he was told that he would be receiving 25 lashes to his head–the head on which he had dared to place tefillin. The officer told him that if he dropped even one of the rocks from his armpits, he would be shot immediately. In fact, because this was such an extremely painful form of death, the officer advised him, “Drop the rocks now. You will never survive the 25 lashes to the head. Nobody ever does.”

“No,” Judah responded, “I won’t give you the pleasure.”

At the 25th lash, Judah lost consciousness and was left for dead. He was about to be dragged to a pile of corpses, and then burned in a ditch, when another Jew saw him, shoved him to the side, and covered his head with a rag, so people wouldn’t realize he was alive. Eventually, after he recovered consciousness, he crawled to the nearest bunkhouse that was on raised piles, and hid under it until he was strong enough to come out under his own power. Two months, on April 29, 1945, the U.S. Seventh Army's 45th Infantry Division liberated Dachau. Judah was free.

During the hanging and beating episode of Judah in the tefilin, a 17-year-old girl had been watching from the women’s side of the fence. After the liberation, she made her way to the men’s camp and found Judah. She walked over to him and said, “I’ve lost everyone. I don’t want to be alone any more. I saw what you did that day when the officer wanted to hang you. Will you marry me?”

The rest is history. The couple walked over to the Klausenberger Rebbe, Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Halberstam, who lost his wife and 11 children in the Holocaust, and requested that he perform the marriage ceremony. The Klausenberger Rebbe wrote out a kesubah (the legal marriage contract required to perform a Jewish marriage) by hand from memory and married them. The young couple ultimately made Aliya and rebuilt their lives in the Holy Land.

“I, Rabbi Yosef Wallis, their son, keep and cherish that kesubah to this day,” Rabbi Wallis concluded his story. “After all, I was born from this marriage.”

The Jewish Eye

Then there is the eye of Jacob. He is, by all counts, a success story. He traveled to a far place and built himself up amazingly well. His own crooked father in law admits that he was blessed with wealth because of Jacob. If only I have now found favor in your eyes! I have divined, and the Lord has blessed me for your sake." He has security, comfort, wealth and a large supporting family. Yet he insists on leaving Laban’s home. He seeks to abandon the home where he spent 20 years. “Jacob said to Laban, ‘Send me away, and I will go to my place and to my land. Give [me] my wives and my children for whom I worked for you, and I will go, for you know my work, which I have worked for you.’"

Why? Because he has an “eye” for the future. Jacob professes long term vision. He is the first Jew to have a dream. In middle of a dark night he dreams of a “ladder standing on earth, and its peak etched in heaven.” So he sees that now he may be comfortable; but if he wants to guarantee the future, there is no way he can educate his children when they are in the environment and under the spell of Laban the crook, the idolater, the liar, and the thief. Jacob must leave, return to his old country, and raise the children near their old grandfather Isaac.

This is what the Midrash intimates when it says that just as the Hadas has many leaves, Jacob had many children. Jacob never considers only the moment; he has an “eye” for the future, a dream for where things are going. He focuses on his children, and on their children, all the way down to our times. Jacob understands that we must not allow our eyes to become blinded by the bliss and ignorance of the present.

It is this Jewish eye, the myrtle leaf, which Jacob bequeathed to us. Do you have an eye for your own future? Do you sacrifice your destiny for present comfort? Do you see the consequences long-term for how you are educating your children today?

Sometimes, we wake up late, because we failed to use our Jewish eyes, our Jewish vision. We got caught up in the moment, and failed to make hard decisions that will transform our future into a blessing. Some people get divorced in haste, ignoring their future. Some people make short term decisions about the schooling and education of their children, not realizing that when these kids grow up they might be lacking the heart, spine and eyes that we didn’t give them out of short sidedness.

The Mouth

Finally, on Sukkos we celebrate the mouth of Joseph. He is the man who gave us the “Jewish mouth.”

As Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, after 22 years of estrangement, they can’t believe it. They are astounded, frightened and overwhelmed. Joseph calms them with these words:

ויגש מה, יב: וְהִנֵּה עֵינֵיכֶם רֹאוֹת וְעֵינֵי אָחִי בִנְיָמִין כִּי פִי הַמְדַבֵּר אֲלֵיכֶם.

And behold, your eyes see, as well as the eyes of my brother Benjamin, that it is my mouth speaking to you.

You see it is my mouth that speaks to you. What does that mean? How do they know it is his mouth? Rashi says, he spoke to them in the “Holy Tongue.” But how did that prove anything, is it not possible that an Egyptian Prime Minister knows Hebrew? We all know plenty of non-Jews who speak a fluent Hebrew, and plenty of Jews who don’t know Hebrew?

Joseph, of course, was not referring only to the technical language, to words, syntax, grammar, and diction. He was referring to a “common language” they shared, what we call in Yiddish, “a Yidishe shprach,” a Jewish shared language. Words express our value system, our priorities, our longings and belief system. As Joseph shared that common language with them they knew he must be their long lost brother. Joseph knew “the language” of the Jewish family; they saw he had a keen awareness of the soul, the weltanschauung, the terms, concepts, quips, euphemisms, cultural associations and passions that no one but their brother could have known.

There is a certain “family language” that a family shares. And there is a certain shared language that Jews have shared over 4000 years.

Joseph bequeaths to us that “Jewish mouth.” Even in Egypt, he never lost that language. Or as the Psalmist puts it: “As a testimony for Josef, when he went forth over the land of Egypt. I heard a language that I had not known.” It was and remains a unique language; how a Jew speaks, how a Jew thinks, how a Jew communicates, how a Jew processes, how a Jew feels.

Even in depraved Egypt, Joseph never lost the language of the Jew. “Shem Shamayim Shagur befev,” the sages say. The name of G-d was a constant on his lips. As a slave, as prisoner and as a Prime Minister. Which is why to further prove he is alive, he sends a message to his father reminding him of their last conversation in Torah learning before Joseph left 22 years earlier. It was that conversation that bonded them across decades and countries. It is that language that still binds us to each other today.

No matter if you are a banker, lawyer, doctor, CPA, a broker, or a barber, we Jews have a “shprach,” a language. Our mouth is shaped to produce words, concepts, sensitivities ingrained in us from the days of Joseph.

[Joseph passed away before his brother, just as the willow dries up before the citrus, palm frond and myrtle. The Jewish language offers dies prematurely. Our grandparents or great grandparents spoke fluent Yiddish; today for most of their grandchildren it is forgotten. Languages that we spoke go through dramatic changes. Who knows Aramaic? Ladino? Esperanto? Yiddish? Yet the soul, the spirit, the faith, the values contained in these languages live on. There is a Jewish way to speak English.]

A Tale of a Black Boy in the Bronx

Unlike today’s vista of decrepit buildings, dilapidated housing and rusting junked cars, the South Bronx in 1950 was the home of a large and thriving community, one that was predominantly Jewish. Today a mere remnant of this once-vibrant community survives, but in the 1950’s the Bronx offered synagogues, mikvahs, kosher bakeries, and kosher butchers — all the comforts one would expect from a traditional Jewish community.

The baby boom of the post-war years happily resulted in many new young parents. As a matter of course, the South Bronx had its own baby equipment store. Sickser’s was located on the corner of Westchester and Fox, and specialized in “everything for the baby,” as its slogan ran. The inventory began with cribs, baby carriages, playpens, high chairs, changing tables, and toys.

Mr. Sickser, assisted by his son-in-law Lou Kirshner, ran a profitable business out of the needs of the rapidly-expanding child population. The language of the store was primarily Yiddish, but Sickser’s was a place where not only Jewish families but also many non-Jewish ones could acquire the necessary paraphernalia for their newly-arrived bundles of joy.

Business was particularly busy one spring day, so much so that Mr. Sickser and his son-in-law could not handle the unexpected throng of customers. Desperate for help, Mr. Sickser ran out of the store and stopped the first youth he spotted on the street.

“Young man,” he panted, “how would you like to make a little extra money? I need some help in the store. You want to work a little?”

The tall, lanky African-American boy flashed a toothy smile back. “Yes, sir, I’d like some work.”

“Well then, let’s get started.” The boy followed his new employer into the store.

Mr. Sickser was immediately impressed with the boy’s good manners and demeanor. As the days went by and he came again and again to lend his help, Mr. Sickser became increasingly impressed with the youth’s diligence, punctuality and readiness to learn. Eventually Mr. Sickser made him a regular employee at the store. It was gratifying to find an employee with an almost soldier-like willingness to perform even the most menial of tasks, and to perform them well.

From the age of 13 until his sophomore year in college, the young man, by the name of Colin, put in from 12-15 hours a week, at 50 to 75 cents an hour. Mostly, he performed general labor: assembling merchandise, unloading trucks and preparing items for shipments. He seemed, in his quiet way, to appreciate not only the steady employment but the friendly atmosphere Mr. Sickser’s store offered. Mr. Sickser learned in time about their helper’s Jamaican origins, and he in turn picked up a good deal of Yiddish. In time young Colin was able to converse fairly well with his employers, and more importantly, with a number of the Jewish customers whose English was not fluent.

After serving two tours of duty in Vietnam, the young man quickly rose to the top ranks of the U.S. military. In 1989, under President George Bush, this young boy, Colin Powell, was sworn in as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and later becomes U.S. Secretary of State.

In 1993, two years after he guided the American victory over Iraq in the Gulf War, Colin Powell visited the Holy Land. Upon meeting Israel’s Prime Minister Yitzchak Shamir in Jerusalem. Shamir was born in Belarus, to family that spoke mainly Yiddish.

So it is 1993. And the Prime Minister of Israel meets the impressive African American General.

They sit down to have a talk.

Colin Powell turns to Shamir and asks: “Men ken reden Yiddish?” — “Do you mind if we speak in Yiddish?”

Shamir almost falls off his chair. He is stunned. As he tried to pull himself together, Colin Powell continued chatting in his second-favorite language. He had never forgotten his early days in the Bronx.

Get Your Four Organs Together

So on Sukkos, G-d tells us: “Take for yourself the Esrog, Lulav, Hadas and Aravah. Embrace the Jewish heart of Abraham; the Jewish spine of Isaac; the Jewish eyes of Jacob, and the Jewish mouth of Joseph. Then you will rejoice before your G-d for seven days. To experience unbridled joy, we must embrace these four dimensions of our lives. Because with these four “organs” in place, you are good to go. You will remain secure, powerful, wholesome, cohesive, and eternal.

Today we must ask ourselves: Do I possess the heart of Abraham? The spine of Isaac? The eyes and vision of Jacob? The mouth of Joseph?

[1] The nucleus of this insight I heard from Rabbi Israel Meir Lau.

[2] Part of this story has been written up in the Jewish Week: http://www.thejewishweek.com/news/new_york/write_students_dedicate_torah_israel

- Comment

Class Summary:

There are some 390,000 plants existing in the world. From all of these the Torah chooses four species for us to shake on Sukkos: The citrus, palm branch, myrtle, and willow. Why these four?

One Midrash gives two strange explanations. The Esrog represents Abraham; the Lulav—Isaac. The Hadas and Aravah—Jacob and Joseph. A few lines later the Midrash sees these four plants as mirroring the heart, spine, eye and mouth.

Both insights beg for explanation. Why are we celebrating these four parts of our body on Sukkos? And the connection with the above four people seems so stretched?

Upon deeper reflection we discover the profundity of the message here. To celebrate seven days of true, unbridled joy we need to learn how to cultivate the gigantic heart of Abraham, the powerful spine of Isaac, the unique eyes of Jacob, and the extraordinary mouth of Joseph.

The sermon tells the story of the African American US Secretary of State who stunned the Israeli Prime Minister when he asked him if he minds if he speaks to him in… Yiddish. We tell the story of American teen-agers who wrote a Torah for a slain Israeli soldier. We tell the story of how the Rebbe persuaded an air-force veteran to become a great Jewish activity and teacher. And the story of a unique marriage created by the display of a psychological Lulav in the Nazi death camp.

On Sukkos, G-d tells us: “Take for yourself the Esrog, Lulav, Hadas and Aravah.” Embrace the Jewish heart of Abraham; the Jewish spine of Isaac; the Jewish eyes of Jacob, and the Jewish mouth of Joseph. Then you will rejoice before your G-d for seven days.

My Daily Regimen

My doctor took one look at my gut and refused to believe that I work out. So I listed the exercises I do every day: jump to conclusions, climb the walls, drag my heels, push my luck, make mountains out of molehills, bend over backward, run around in circles, put my foot in my mouth, go over the edge, and beat around the bush.

The Psychiatrist

At psychiatrist:

- Do you consume alcohol?

- No.

- Do you smoke?

- No.

- Do you use drugs?

- No.

- Do you play cards?

- No.

- Do you run after other women?

- No.

- So why did you come to me?

- You see, doc, I have one little problem - I lie a lot...

The Four Species

Comes Sukkos, and Jews the world over become expert botanists, suddenly gaining impeccable tastes in the growth, health, and beauty of a citron fruit, a palm branch, a myrtle and a willow. These are the four species which Jews around the world have spent exorbitant amounts of money to buy what they perceived to be the best and most perfect of these four species. We hold on to these four types for the seven days of Sukkos, we shake them every day, and we treat them like little princesses.

It comes straight from Leviticus:

אמור כג, מ: וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי נָחַל וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים.

And you shall take for yourselves on the first day, the splendid tree-fruit, date palm fronds, a branch of a braided tree, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your G-d for a seven day period.

But why these four?

Do you know how many plants there are in the world? The total number of plant species in the world is estimated at 390,900 by the Royal Botanic Gardens. Approximately 1,000 to 2,000 species of plants are edible by humans. About 100 to 200 species of plants play an important role in world commerce, and about 15 species provide the majority of food crops. (These include soybeans, peanuts, rice, wheat and bananas.)

There are estimated to be about 7500 types of just apples and 1600 types of bananas alone. To put that in perspective, if you ate a new type of apple each day, it would take you a little over twenty years to try them all. For the bananas, it's a little over four years.

So the obvious question is, why does the Torah choose from among 390,000 pants to take these four species on Sukkos? The citrus, palm branch, myrtle, and willow. They are not even edible fruits and plants!

Four Persons

Over millennia, scores of insights have been offered. Two of them (among others) are quoted in the Midrash, and they both seem strange.

ויקרא רבה ל, י: "פרי עץ הדר" - זה אברהם, שהדרו הקדוש ברוך הוא בשיבה טובה, שנאמר (בראשית כד, א): "ואברהם זקן בא בימים", וכתיב (ויקרא יט, לב): "והדרת פני זקן", "כפות תמרים" - זה יצחק, שהיה כפות ועקוד על גבי המזבח. "וענף עץ עבות" - זה יעקב, מה הדס זה רחוש בעלין כך היה יעקב רחוש בבנים. "וערבי נחל" - זה יוסף, מה ערבה זו כמושה לפני ג' מינין הללו כך מת יוסף לפני אחיו.

The Midrash explains that these four species represents our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph. The “beautiful fruit” represents Abraham, beautified by old age. “And Abraham grew old; he came in his days,” Genesis says.

The palm branch combining all the leaves and binding them together [The Torah writes, “fronds of dates,” but the word kapot (“fronds of”) also means “bound,” implying that we are to take a closed frond, the heart of the palm], reminds of us of Isaac who was bound on the altar.

Jacob had many children just as the myrtle branch is full of leaves. Joseph died before his brother just as the willow withers before the other three plants.

This begs for an explanation. The connection between these four types of plants and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and Joseph appears like a stretch. Also, why do we want to remind ourselves on Sukkos of these particular four people? Furthermore, must we use plants to recall them?

Four Organs

A few lines later, the Midrash gives us another insight:

ויקרא רבה ל, יד: יד רבי מני פתח (תהלים לה, י): "כל עצמותי תאמרנה ה' מי כמוך" לא נאמר פסוק זה אלא בשביל לולב. השדרה של לולב דומה לשדרה של אדם. וההדס דומה לעין. וערבה דומה לפה. והאתרוג דומה ללב. אמר דוד אין בכל האיברים גדול מאלו שהן שקולין כנגד כל הגוף הוי "כל עצמותי תאמרנה":

The four plants reflect four major parts of the human body. (Demonstrate to your crowd, by lifting up each type and perhaps a large image of a heart, spine, eye and mouth). The citrus looks like the heart. The Lulav mirrors the human spine. The hadas leaf is shaped like an eye. The willow leaf is shaped like a mouth.

This is charming. But here too we must ask, why are trying to recall these four parts of our body?

Perhaps, the two explanations in the Midrash are interrelated. On Sukkos we are invited to “take to ourselves” the heart, spine, eye and mouth. But of whom? Of Abaraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. On this holiday we are charged with the mission to embracing the Esrog—the heart of Abraham; the Lulav—the spine of Isaac; the Hadas—the eyes of Jacob; and Arravah—the mouth of Joseph.[1]

The Jewish Heart

The heart of Abraham represents the legendary and timeless “Jewish heart.”

A Jew walked in to a shul in New York in 1949. No one knew him. No one owed him anything. A complete stranger. But people walked over to him: Sholom Aleichem! Where are you from? Do you have where to stay? Do you have where to eat? Which city you come from? Ah! You knew my uncle. Which camp did you survive? How did you make it out of here? You need help finding a job? Did you maybe meet anyone of my family in the D.P. camps?

And a Jew walks in to a shul in 2017. The questions may be different, but the heart—the heart of Abraham, the heart filled with sensitivity, love to mankind—is the same. The same Jewish heart, the heart of the man who had a tent with four doors, on all sides, to welcome guests from all directions—still beats in our organisms 3600 years later.

“Chesed L’Avraham,” the prophet says. Kindness belongs to Abraham. This was the “hadar,” the beauty and splendor he was blessed with.

The Function of a Heart

Rabbi Moshe Tzur, an Israeli Air Force veteran, now lives with his family in Jerusalem, Israel. After his service in the Air Force, he went on to found a number of yeshivos.

He related this story.

In 1969, when I was serving in the Israeli Air Force – during the hard times in the aftermath of the Six Day War, when soldiers did not have much food to eat – I remember a jeep pulling up and someone handing me a package. A note on the package said, “Purim Samayach mehaRebbe miLubavitch – Happy Purim from the Lubavitcher Rebbe.”

I remember wondering, as did every soldier who got the same package, “Who is this Rebbe of Lubavitch? Why does he care so much about us to deliver sweets to us in the middle of the desert?” I must say I was touched and impressed.

In 1971, I was sent to the Suez Canal to bring back wounded soldiers to the hospital in the north. I did this day after day, and it was really very difficult to see so many gravely wounded. One day, my convoy came across two Chabad people who asked us to put teffilin on. I did, and when I recited the Shema prayer – “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is one” – I became very emotional and started crying. From that moment began my journey of return to Judaism.

When I finished my military service, I came to New York and I met the Rebbe.

In one of my meetings with the Rebbe he asked me what I was doing for the Jewish community. And he spoke to me about the commandment to love your neighbor as yourself.

As the conversation got more intense and involved, the Rebbe finally turned to me and said:

I have a question. Which is the most important limb after the brain?

“The heart.”

And which is the more important side in Judaism? Right or left?

For sure the right. Joseph is upset when his father places his left hand on the oldest son. The right is associated with more love, closeness, and vigor.

So, asked the Rebbe, why is the heart on the left side of the body? Everything important in Judaism is on the right side. We put on tefillin with the right hand, we put the mezuzah on the right side of the door, we shake hands with the right hand, we hold the Torah scroll on our right side, in the Temple they always waked to the right, so why is the heart—the organ responsible for our blood and vitality—is on the left?”

The man remained silent.

I will tell you the answer, said the Rebbe. The heart is really to the right, not to the left.

You see, the heart of a person is made to feel, to emphasize with, to connect, to be there for another person, for another Jew. My heart was given to me to feel your pain, your needs, and your concerns. My heart was given to me to experience the soul and the heart of the person standing in front of me. My heart is here for you. And from your vantage point, my heart is on your right!…

When you face another Jew, your heart is opposite his right side. For your heart beats not for you but for the other, for the fellow whom you must love as yourself.

This message really spoke to me, and I adopted it as the center of my philosophy of life. And, since then, my mission in life has been to reach the heart of every Jew that I meet.

After succeeding in business in Chicago, I returned to Israel, and I established two important yeshivot. One yeshiva is called Aish HaTalmud; it is a yeshiva high school with almost two hundred boys enrolled. The other is called Torat Moshe, with about ninety-five boys. I have also established four kollelim, study groups for married men, with almost a hundred-twenty enrolled.

I also founded an organization to support poor families for Rosh Hashanah and Passover. These are people who don’t have much income, and we help them with food and money.

All this because of the words of the Rebbe – that the key is to help others – which changed my perspective on life and shaped my life’s mission.

A Scroll on Mt. Herzl

It all happened on a simple day back in 2011.[2] A group of 50 Jewish teenagers visited Israel in a program known as “Write on For Israel,” in which these youngsters spend a few intense weeks learning much of the history and the reality of Israel, as a training program for them to become spokesmen for Israel at their future schools and campuses.

As their visit was coming to an end, just a few hours before their flight back home to the US, the kids visited Mt. Herzl, gazing at the thousands of graves of Israeli soldiers killed in battle over the last seven decades.

Suddenly they noticed a mom and dad standing at a grave, weeping silently. One of the boys approached them, introduced himself, and inquired about the person buried in the grave.

They said it was their son Erez. Erez Deri, the son of Penina and Gidon Deri, was killed in 2006 following an operation in Jenin. He went in to Jenin, the center for dispatching suicide bombers to murder as many Jews as possible, to take on the killers. His tank turned over and he was killed.

Erez’s mother said:

“Our dream was to bring Erez to the chupah… to watch him get married and begin a family. But in 2006, our dream was shattered. Our family has been devastated as a result of this tragedy.

“Last night, Erez came to me in a dream. He said: Mother! We bring our children into chupah. But there is one more thing we “bring in to the chupah:” A Torah Scroll. When we complete writing a Torah, we lead it under a chupah, just like a groom and bride, and we bring it in to a shul, singing and dancing, just like a wedding.

“You can’t bring me into marriage. But you know what? Why not write a Torah in my name and you will bring that it to a chupah—it will be like marrying me off!”

And the mother continues: I awoke from the dream. But we are a simple family, not wealthy. We are also a secular family, and do not know much about writing a Torah Scroll. I do not even know where to begin. How do I write a Torah for my son Erez? So I came to here to my son’s grave to pray…”

The teenager approached the director of their group, Rabbi Yutav Eliach, and asked him one question:

How much does it cost to write a new Torah?

$35,000. Or, 130,000 Shekel, he said.

The teenager shared the story with the entire group. They all decided right there at Mt. Herzl to donate the Torah for Erez.

They did the math. If each of the 50 students gave or raised $700 it would cover the entire project.

Many of them stuck their hands into their pockets and gave Rabbi Yutav the $700. The others pledged to deliver him the money they would raise upon their return to the US.

A few month later, a surreal scene took place in Maale Adumim, a town close to Jerusalem, where Erez’s family lives. It was Sunday, March 4, 2012. With music blasting, 50 New York-area teens from Write On For Israel, danced up the streets of this West Bank community with a Sefer Torah they brought from the United States. The Torah was donated to a local synagogue in memory of one of its young members, fallen IDF soldier Erez Deri.

The 50 students fulfilled the promise made to Deri’s parents following a chance meeting at Mount Herzl a few months earlier.

“We started as strangers and returned as extended members of the Deri family,” said Daniella Greenbaum, leader of the fundraising effort. “It was beyond exciting to see the joy that we brought to these parents and to affirm the idea that we are all members of Am Yisrael, responsible for one another.”

At the celebration, Penina Erez, said to the students: I feel the presence of Erez at this celebration. I feel like I brought my child into the chupah! I feel like he is dancing with us. A terrible burden has been lifted from our family.

A few months later, the family celebrated the wedding of one of Erez’s brothers.

This is the embodiment of the Jewish heart—the Esrog. The heart of Abraham. A heart that feels the pain, the needs, the plight and the soul of another human being.

The Spine

The Lulav represents the “Jewish spine.” This is the spine and sense of confidence and pride represented by Isaac who with an upright posture walked to the altar and allowed himself, like the fronds of the palm, to be bound. As Abraham tells him that G-d chose him as an offering, the Torah states, “they walked together.” Isaac continues to walk upright. He does not duck, bend, or run.

Isaac bequeathed that “spine,” the Lulav, to us—the ability for us to make sacrifices for truth, for G-d, for Yiddishkeit, with vigor, pride, dignity and unwavering resolve. We need not apologize for being Jewish, and become defensive, meek, bent, or repressed. We carry our Jewishness with full confidence and dignity. We stand erect. We are capable of standing up for our people and our faith with pride and full stature.

A King in Dachau

Rabbi Yosef Wallis living today in Israel related the following story he heard from his father. For me, it captures the image of a Jew who even in the hell of hells never forfeits his spine, his Lulav; he sees himself as a King. Even in a place where they stripped you from every notion of value, this man did not duck.

While his father, Judah, was in the Dachau concentration camp, a Jew who was being taken to his death suddenly flung a small bag at Judah Wallis. He caught it, thinking it might contain a piece of bread. Upon opening it, however, he discovered a pair of tefilin (the phylacteries donned each morning by Jewish men). Judah was very frightened because he knew that were he to be caught carrying tefillin, he would be put to death instantly. So he hid the tefillin under his shirt and headed for his bunkhouse.

In the morning, just before the roll call, while still in his bunkhouse, he would put on the tefillin. One morning, unexpectedly, a German officer appeared. He ordered him to remove the tefillin, noted the number on Judah’s arm, and ordered him to go straight to the roll call.

At the roll call, in front of thousands of silent Jews, the officer called out Judah’s number and he had no choice but to step forward. The German officer waved the tefillin in the air and screamed, “Dog! I sentence you to death by public hanging for wearing these!”

Judah was placed on a stool and a noose was placed around his neck. Before he was hanged, the officer said in a mocking tone, “Dog, what is your last wish?” “To wear my tefillin one last time,” Judah replied.

The SS officer was dumbfounded. He handed Judah the tefillin. As Judah put them on, he recited the incredibly moving verse from the prophet Hosea that many Jews say while winding the tefillin around the fingers: “Ve’eirastich li le’olam, ve’eirastich li b’tzedek ub’mishpat, ub’chessed, ub’rachamim, ve’eirastich li b’emunah, v’yodaat es Hashem;” I will betroth you to Me forever and I will betroth you to Me with righteousness, and with justice, and with kindness, and with mercy, and I will betroth you to Me with loyalty, and you shall know G-d.

In silence, the entire camped looked on at the Jew with a noose around his neck, and tefillin on his head and arm, awaiting his death for the ‘crime’ of observing this mitzvah. Even women from the adjoining camp were lined up at the barbed wire fence that separated them from the men’s camp, compelled to watch this ominous sight.

As Judah turned to the silent crowd, he saw tears in many people’s eyes. Even at that moment, as he was about to be hanged, he was shocked: Jews were crying! How was it possible that they still had tears left to shed? And for a stranger? Where were those tears coming from? Impulsively, in Yiddish, he called out, “Yidden, don’t cry. With tefillin on, I am the victor! Don’t you understand? The victory is mine!”

The German officer understood the Yiddish and was infuriated. He said to Judah, “You dog, you think you are the victor? Hanging is too good for you. You are going to get another kind of death.”

Judah was taken from the stool, and the noose was removed from his neck. He was forced into a squatting position and two large rocks were placed under his armpits. Then he was told that he would be receiving 25 lashes to his head–the head on which he had dared to place tefillin. The officer told him that if he dropped even one of the rocks from his armpits, he would be shot immediately. In fact, because this was such an extremely painful form of death, the officer advised him, “Drop the rocks now. You will never survive the 25 lashes to the head. Nobody ever does.”

“No,” Judah responded, “I won’t give you the pleasure.”

At the 25th lash, Judah lost consciousness and was left for dead. He was about to be dragged to a pile of corpses, and then burned in a ditch, when another Jew saw him, shoved him to the side, and covered his head with a rag, so people wouldn’t realize he was alive. Eventually, after he recovered consciousness, he crawled to the nearest bunkhouse that was on raised piles, and hid under it until he was strong enough to come out under his own power. Two months, on April 29, 1945, the U.S. Seventh Army's 45th Infantry Division liberated Dachau. Judah was free.

During the hanging and beating episode of Judah in the tefilin, a 17-year-old girl had been watching from the women’s side of the fence. After the liberation, she made her way to the men’s camp and found Judah. She walked over to him and said, “I’ve lost everyone. I don’t want to be alone any more. I saw what you did that day when the officer wanted to hang you. Will you marry me?”

The rest is history. The couple walked over to the Klausenberger Rebbe, Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Halberstam, who lost his wife and 11 children in the Holocaust, and requested that he perform the marriage ceremony. The Klausenberger Rebbe wrote out a kesubah (the legal marriage contract required to perform a Jewish marriage) by hand from memory and married them. The young couple ultimately made Aliya and rebuilt their lives in the Holy Land.

“I, Rabbi Yosef Wallis, their son, keep and cherish that kesubah to this day,” Rabbi Wallis concluded his story. “After all, I was born from this marriage.”

The Jewish Eye

Then there is the eye of Jacob. He is, by all counts, a success story. He traveled to a far place and built himself up amazingly well. His own crooked father in law admits that he was blessed with wealth because of Jacob. If only I have now found favor in your eyes! I have divined, and the Lord has blessed me for your sake." He has security, comfort, wealth and a large supporting family. Yet he insists on leaving Laban’s home. He seeks to abandon the home where he spent 20 years. “Jacob said to Laban, ‘Send me away, and I will go to my place and to my land. Give [me] my wives and my children for whom I worked for you, and I will go, for you know my work, which I have worked for you.’"

Why? Because he has an “eye” for the future. Jacob professes long term vision. He is the first Jew to have a dream. In middle of a dark night he dreams of a “ladder standing on earth, and its peak etched in heaven.” So he sees that now he may be comfortable; but if he wants to guarantee the future, there is no way he can educate his children when they are in the environment and under the spell of Laban the crook, the idolater, the liar, and the thief. Jacob must leave, return to his old country, and raise the children near their old grandfather Isaac.

This is what the Midrash intimates when it says that just as the Hadas has many leaves, Jacob had many children. Jacob never considers only the moment; he has an “eye” for the future, a dream for where things are going. He focuses on his children, and on their children, all the way down to our times. Jacob understands that we must not allow our eyes to become blinded by the bliss and ignorance of the present.

It is this Jewish eye, the myrtle leaf, which Jacob bequeathed to us. Do you have an eye for your own future? Do you sacrifice your destiny for present comfort? Do you see the consequences long-term for how you are educating your children today?

Sometimes, we wake up late, because we failed to use our Jewish eyes, our Jewish vision. We got caught up in the moment, and failed to make hard decisions that will transform our future into a blessing. Some people get divorced in haste, ignoring their future. Some people make short term decisions about the schooling and education of their children, not realizing that when these kids grow up they might be lacking the heart, spine and eyes that we didn’t give them out of short sidedness.

The Mouth

Finally, on Sukkos we celebrate the mouth of Joseph. He is the man who gave us the “Jewish mouth.”

As Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, after 22 years of estrangement, they can’t believe it. They are astounded, frightened and overwhelmed. Joseph calms them with these words:

ויגש מה, יב: וְהִנֵּה עֵינֵיכֶם רֹאוֹת וְעֵינֵי אָחִי בִנְיָמִין כִּי פִי הַמְדַבֵּר אֲלֵיכֶם.

And behold, your eyes see, as well as the eyes of my brother Benjamin, that it is my mouth speaking to you.

You see it is my mouth that speaks to you. What does that mean? How do they know it is his mouth? Rashi says, he spoke to them in the “Holy Tongue.” But how did that prove anything, is it not possible that an Egyptian Prime Minister knows Hebrew? We all know plenty of non-Jews who speak a fluent Hebrew, and plenty of Jews who don’t know Hebrew?

Joseph, of course, was not referring only to the technical language, to words, syntax, grammar, and diction. He was referring to a “common language” they shared, what we call in Yiddish, “a Yidishe shprach,” a Jewish shared language. Words express our value system, our priorities, our longings and belief system. As Joseph shared that common language with them they knew he must be their long lost brother. Joseph knew “the language” of the Jewish family; they saw he had a keen awareness of the soul, the weltanschauung, the terms, concepts, quips, euphemisms, cultural associations and passions that no one but their brother could have known.

There is a certain “family language” that a family shares. And there is a certain shared language that Jews have shared over 4000 years.

Joseph bequeaths to us that “Jewish mouth.” Even in Egypt, he never lost that language. Or as the Psalmist puts it: “As a testimony for Josef, when he went forth over the land of Egypt. I heard a language that I had not known.” It was and remains a unique language; how a Jew speaks, how a Jew thinks, how a Jew communicates, how a Jew processes, how a Jew feels.

Even in depraved Egypt, Joseph never lost the language of the Jew. “Shem Shamayim Shagur befev,” the sages say. The name of G-d was a constant on his lips. As a slave, as prisoner and as a Prime Minister. Which is why to further prove he is alive, he sends a message to his father reminding him of their last conversation in Torah learning before Joseph left 22 years earlier. It was that conversation that bonded them across decades and countries. It is that language that still binds us to each other today.

No matter if you are a banker, lawyer, doctor, CPA, a broker, or a barber, we Jews have a “shprach,” a language. Our mouth is shaped to produce words, concepts, sensitivities ingrained in us from the days of Joseph.

[Joseph passed away before his brother, just as the willow dries up before the citrus, palm frond and myrtle. The Jewish language offers dies prematurely. Our grandparents or great grandparents spoke fluent Yiddish; today for most of their grandchildren it is forgotten. Languages that we spoke go through dramatic changes. Who knows Aramaic? Ladino? Esperanto? Yiddish? Yet the soul, the spirit, the faith, the values contained in these languages live on. There is a Jewish way to speak English.]

A Tale of a Black Boy in the Bronx

Unlike today’s vista of decrepit buildings, dilapidated housing and rusting junked cars, the South Bronx in 1950 was the home of a large and thriving community, one that was predominantly Jewish. Today a mere remnant of this once-vibrant community survives, but in the 1950’s the Bronx offered synagogues, mikvahs, kosher bakeries, and kosher butchers — all the comforts one would expect from a traditional Jewish community.

The baby boom of the post-war years happily resulted in many new young parents. As a matter of course, the South Bronx had its own baby equipment store. Sickser’s was located on the corner of Westchester and Fox, and specialized in “everything for the baby,” as its slogan ran. The inventory began with cribs, baby carriages, playpens, high chairs, changing tables, and toys.

Mr. Sickser, assisted by his son-in-law Lou Kirshner, ran a profitable business out of the needs of the rapidly-expanding child population. The language of the store was primarily Yiddish, but Sickser’s was a place where not only Jewish families but also many non-Jewish ones could acquire the necessary paraphernalia for their newly-arrived bundles of joy.

Business was particularly busy one spring day, so much so that Mr. Sickser and his son-in-law could not handle the unexpected throng of customers. Desperate for help, Mr. Sickser ran out of the store and stopped the first youth he spotted on the street.

“Young man,” he panted, “how would you like to make a little extra money? I need some help in the store. You want to work a little?”

The tall, lanky African-American boy flashed a toothy smile back. “Yes, sir, I’d like some work.”

“Well then, let’s get started.” The boy followed his new employer into the store.

Mr. Sickser was immediately impressed with the boy’s good manners and demeanor. As the days went by and he came again and again to lend his help, Mr. Sickser became increasingly impressed with the youth’s diligence, punctuality and readiness to learn. Eventually Mr. Sickser made him a regular employee at the store. It was gratifying to find an employee with an almost soldier-like willingness to perform even the most menial of tasks, and to perform them well.

From the age of 13 until his sophomore year in college, the young man, by the name of Colin, put in from 12-15 hours a week, at 50 to 75 cents an hour. Mostly, he performed general labor: assembling merchandise, unloading trucks and preparing items for shipments. He seemed, in his quiet way, to appreciate not only the steady employment but the friendly atmosphere Mr. Sickser’s store offered. Mr. Sickser learned in time about their helper’s Jamaican origins, and he in turn picked up a good deal of Yiddish. In time young Colin was able to converse fairly well with his employers, and more importantly, with a number of the Jewish customers whose English was not fluent.

After serving two tours of duty in Vietnam, the young man quickly rose to the top ranks of the U.S. military. In 1989, under President George Bush, this young boy, Colin Powell, was sworn in as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and later becomes U.S. Secretary of State.

In 1993, two years after he guided the American victory over Iraq in the Gulf War, Colin Powell visited the Holy Land. Upon meeting Israel’s Prime Minister Yitzchak Shamir in Jerusalem. Shamir was born in Belarus, to family that spoke mainly Yiddish.

So it is 1993. And the Prime Minister of Israel meets the impressive African American General.

They sit down to have a talk.

Colin Powell turns to Shamir and asks: “Men ken reden Yiddish?” — “Do you mind if we speak in Yiddish?”

Shamir almost falls off his chair. He is stunned. As he tried to pull himself together, Colin Powell continued chatting in his second-favorite language. He had never forgotten his early days in the Bronx.

Get Your Four Organs Together

So on Sukkos, G-d tells us: “Take for yourself the Esrog, Lulav, Hadas and Aravah. Embrace the Jewish heart of Abraham; the Jewish spine of Isaac; the Jewish eyes of Jacob, and the Jewish mouth of Joseph. Then you will rejoice before your G-d for seven days. To experience unbridled joy, we must embrace these four dimensions of our lives. Because with these four “organs” in place, you are good to go. You will remain secure, powerful, wholesome, cohesive, and eternal.

Today we must ask ourselves: Do I possess the heart of Abraham? The spine of Isaac? The eyes and vision of Jacob? The mouth of Joseph?

[1] The nucleus of this insight I heard from Rabbi Israel Meir Lau.

[2] Part of this story has been written up in the Jewish Week: http://www.thejewishweek.com/news/new_york/write_students_dedicate_torah_israel

Categories

Sukkos 5778

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2017

- |

- 13 Tishrei 5778

- |

- 9 views

A Jewish Heart, Spine, Eye and Mouth

How the Four Species Reflect the Lives of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- October 3, 2017

My Daily Regimen

My doctor took one look at my gut and refused to believe that I work out. So I listed the exercises I do every day: jump to conclusions, climb the walls, drag my heels, push my luck, make mountains out of molehills, bend over backward, run around in circles, put my foot in my mouth, go over the edge, and beat around the bush.

The Psychiatrist

At psychiatrist:

- Do you consume alcohol?

- No.

- Do you smoke?

- No.

- Do you use drugs?

- No.

- Do you play cards?

- No.

- Do you run after other women?

- No.

- So why did you come to me?

- You see, doc, I have one little problem - I lie a lot...

The Four Species

Comes Sukkos, and Jews the world over become expert botanists, suddenly gaining impeccable tastes in the growth, health, and beauty of a citron fruit, a palm branch, a myrtle and a willow. These are the four species which Jews around the world have spent exorbitant amounts of money to buy what they perceived to be the best and most perfect of these four species. We hold on to these four types for the seven days of Sukkos, we shake them every day, and we treat them like little princesses.

It comes straight from Leviticus:

אמור כג, מ: וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי נָחַל וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים.

And you shall take for yourselves on the first day, the splendid tree-fruit, date palm fronds, a branch of a braided tree, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your G-d for a seven day period.

But why these four?

Do you know how many plants there are in the world? The total number of plant species in the world is estimated at 390,900 by the Royal Botanic Gardens. Approximately 1,000 to 2,000 species of plants are edible by humans. About 100 to 200 species of plants play an important role in world commerce, and about 15 species provide the majority of food crops. (These include soybeans, peanuts, rice, wheat and bananas.)

There are estimated to be about 7500 types of just apples and 1600 types of bananas alone. To put that in perspective, if you ate a new type of apple each day, it would take you a little over twenty years to try them all. For the bananas, it's a little over four years.

So the obvious question is, why does the Torah choose from among 390,000 pants to take these four species on Sukkos? The citrus, palm branch, myrtle, and willow. They are not even edible fruits and plants!

Four Persons

Over millennia, scores of insights have been offered. Two of them (among others) are quoted in the Midrash, and they both seem strange.

ויקרא רבה ל, י: "פרי עץ הדר" - זה אברהם, שהדרו הקדוש ברוך הוא בשיבה טובה, שנאמר (בראשית כד, א): "ואברהם זקן בא בימים", וכתיב (ויקרא יט, לב): "והדרת פני זקן", "כפות תמרים" - זה יצחק, שהיה כפות ועקוד על גבי המזבח. "וענף עץ עבות" - זה יעקב, מה הדס זה רחוש בעלין כך היה יעקב רחוש בבנים. "וערבי נחל" - זה יוסף, מה ערבה זו כמושה לפני ג' מינין הללו כך מת יוסף לפני אחיו.

The Midrash explains that these four species represents our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph. The “beautiful fruit” represents Abraham, beautified by old age. “And Abraham grew old; he came in his days,” Genesis says.

The palm branch combining all the leaves and binding them together [The Torah writes, “fronds of dates,” but the word kapot (“fronds of”) also means “bound,” implying that we are to take a closed frond, the heart of the palm], reminds of us of Isaac who was bound on the altar.

Jacob had many children just as the myrtle branch is full of leaves. Joseph died before his brother just as the willow withers before the other three plants.

This begs for an explanation. The connection between these four types of plants and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and Joseph appears like a stretch. Also, why do we want to remind ourselves on Sukkos of these particular four people? Furthermore, must we use plants to recall them?

Four Organs

A few lines later, the Midrash gives us another insight:

ויקרא רבה ל, יד: יד רבי מני פתח (תהלים לה, י): "כל עצמותי תאמרנה ה' מי כמוך" לא נאמר פסוק זה אלא בשביל לולב. השדרה של לולב דומה לשדרה של אדם. וההדס דומה לעין. וערבה דומה לפה. והאתרוג דומה ללב. אמר דוד אין בכל האיברים גדול מאלו שהן שקולין כנגד כל הגוף הוי "כל עצמותי תאמרנה":

The four plants reflect four major parts of the human body. (Demonstrate to your crowd, by lifting up each type and perhaps a large image of a heart, spine, eye and mouth). The citrus looks like the heart. The Lulav mirrors the human spine. The hadas leaf is shaped like an eye. The willow leaf is shaped like a mouth.

This is charming. But here too we must ask, why are trying to recall these four parts of our body?

Perhaps, the two explanations in the Midrash are interrelated. On Sukkos we are invited to “take to ourselves” the heart, spine, eye and mouth. But of whom? Of Abaraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. On this holiday we are charged with the mission to embracing the Esrog—the heart of Abraham; the Lulav—the spine of Isaac; the Hadas—the eyes of Jacob; and Arravah—the mouth of Joseph.[1]

The Jewish Heart

The heart of Abraham represents the legendary and timeless “Jewish heart.”

A Jew walked in to a shul in New York in 1949. No one knew him. No one owed him anything. A complete stranger. But people walked over to him: Sholom Aleichem! Where are you from? Do you have where to stay? Do you have where to eat? Which city you come from? Ah! You knew my uncle. Which camp did you survive? How did you make it out of here? You need help finding a job? Did you maybe meet anyone of my family in the D.P. camps?

And a Jew walks in to a shul in 2017. The questions may be different, but the heart—the heart of Abraham, the heart filled with sensitivity, love to mankind—is the same. The same Jewish heart, the heart of the man who had a tent with four doors, on all sides, to welcome guests from all directions—still beats in our organisms 3600 years later.

“Chesed L’Avraham,” the prophet says. Kindness belongs to Abraham. This was the “hadar,” the beauty and splendor he was blessed with.

The Function of a Heart

Rabbi Moshe Tzur, an Israeli Air Force veteran, now lives with his family in Jerusalem, Israel. After his service in the Air Force, he went on to found a number of yeshivos.

He related this story.

In 1969, when I was serving in the Israeli Air Force – during the hard times in the aftermath of the Six Day War, when soldiers did not have much food to eat – I remember a jeep pulling up and someone handing me a package. A note on the package said, “Purim Samayach mehaRebbe miLubavitch – Happy Purim from the Lubavitcher Rebbe.”

I remember wondering, as did every soldier who got the same package, “Who is this Rebbe of Lubavitch? Why does he care so much about us to deliver sweets to us in the middle of the desert?” I must say I was touched and impressed.

In 1971, I was sent to the Suez Canal to bring back wounded soldiers to the hospital in the north. I did this day after day, and it was really very difficult to see so many gravely wounded. One day, my convoy came across two Chabad people who asked us to put teffilin on. I did, and when I recited the Shema prayer – “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is one” – I became very emotional and started crying. From that moment began my journey of return to Judaism.

When I finished my military service, I came to New York and I met the Rebbe.

In one of my meetings with the Rebbe he asked me what I was doing for the Jewish community. And he spoke to me about the commandment to love your neighbor as yourself.

As the conversation got more intense and involved, the Rebbe finally turned to me and said:

I have a question. Which is the most important limb after the brain?

“The heart.”

And which is the more important side in Judaism? Right or left?

For sure the right. Joseph is upset when his father places his left hand on the oldest son. The right is associated with more love, closeness, and vigor.

So, asked the Rebbe, why is the heart on the left side of the body? Everything important in Judaism is on the right side. We put on tefillin with the right hand, we put the mezuzah on the right side of the door, we shake hands with the right hand, we hold the Torah scroll on our right side, in the Temple they always waked to the right, so why is the heart—the organ responsible for our blood and vitality—is on the left?”

The man remained silent.

I will tell you the answer, said the Rebbe. The heart is really to the right, not to the left.

You see, the heart of a person is made to feel, to emphasize with, to connect, to be there for another person, for another Jew. My heart was given to me to feel your pain, your needs, and your concerns. My heart was given to me to experience the soul and the heart of the person standing in front of me. My heart is here for you. And from your vantage point, my heart is on your right!…

When you face another Jew, your heart is opposite his right side. For your heart beats not for you but for the other, for the fellow whom you must love as yourself.

This message really spoke to me, and I adopted it as the center of my philosophy of life. And, since then, my mission in life has been to reach the heart of every Jew that I meet.

After succeeding in business in Chicago, I returned to Israel, and I established two important yeshivot. One yeshiva is called Aish HaTalmud; it is a yeshiva high school with almost two hundred boys enrolled. The other is called Torat Moshe, with about ninety-five boys. I have also established four kollelim, study groups for married men, with almost a hundred-twenty enrolled.

I also founded an organization to support poor families for Rosh Hashanah and Passover. These are people who don’t have much income, and we help them with food and money.

All this because of the words of the Rebbe – that the key is to help others – which changed my perspective on life and shaped my life’s mission.

A Scroll on Mt. Herzl

It all happened on a simple day back in 2011.[2] A group of 50 Jewish teenagers visited Israel in a program known as “Write on For Israel,” in which these youngsters spend a few intense weeks learning much of the history and the reality of Israel, as a training program for them to become spokesmen for Israel at their future schools and campuses.

As their visit was coming to an end, just a few hours before their flight back home to the US, the kids visited Mt. Herzl, gazing at the thousands of graves of Israeli soldiers killed in battle over the last seven decades.

Suddenly they noticed a mom and dad standing at a grave, weeping silently. One of the boys approached them, introduced himself, and inquired about the person buried in the grave.

They said it was their son Erez. Erez Deri, the son of Penina and Gidon Deri, was killed in 2006 following an operation in Jenin. He went in to Jenin, the center for dispatching suicide bombers to murder as many Jews as possible, to take on the killers. His tank turned over and he was killed.

Erez’s mother said:

“Our dream was to bring Erez to the chupah… to watch him get married and begin a family. But in 2006, our dream was shattered. Our family has been devastated as a result of this tragedy.

“Last night, Erez came to me in a dream. He said: Mother! We bring our children into chupah. But there is one more thing we “bring in to the chupah:” A Torah Scroll. When we complete writing a Torah, we lead it under a chupah, just like a groom and bride, and we bring it in to a shul, singing and dancing, just like a wedding.

“You can’t bring me into marriage. But you know what? Why not write a Torah in my name and you will bring that it to a chupah—it will be like marrying me off!”

And the mother continues: I awoke from the dream. But we are a simple family, not wealthy. We are also a secular family, and do not know much about writing a Torah Scroll. I do not even know where to begin. How do I write a Torah for my son Erez? So I came to here to my son’s grave to pray…”

The teenager approached the director of their group, Rabbi Yutav Eliach, and asked him one question:

How much does it cost to write a new Torah?

$35,000. Or, 130,000 Shekel, he said.

The teenager shared the story with the entire group. They all decided right there at Mt. Herzl to donate the Torah for Erez.

They did the math. If each of the 50 students gave or raised $700 it would cover the entire project.

Many of them stuck their hands into their pockets and gave Rabbi Yutav the $700. The others pledged to deliver him the money they would raise upon their return to the US.

A few month later, a surreal scene took place in Maale Adumim, a town close to Jerusalem, where Erez’s family lives. It was Sunday, March 4, 2012. With music blasting, 50 New York-area teens from Write On For Israel, danced up the streets of this West Bank community with a Sefer Torah they brought from the United States. The Torah was donated to a local synagogue in memory of one of its young members, fallen IDF soldier Erez Deri.

The 50 students fulfilled the promise made to Deri’s parents following a chance meeting at Mount Herzl a few months earlier.

“We started as strangers and returned as extended members of the Deri family,” said Daniella Greenbaum, leader of the fundraising effort. “It was beyond exciting to see the joy that we brought to these parents and to affirm the idea that we are all members of Am Yisrael, responsible for one another.”

At the celebration, Penina Erez, said to the students: I feel the presence of Erez at this celebration. I feel like I brought my child into the chupah! I feel like he is dancing with us. A terrible burden has been lifted from our family.

A few months later, the family celebrated the wedding of one of Erez’s brothers.

This is the embodiment of the Jewish heart—the Esrog. The heart of Abraham. A heart that feels the pain, the needs, the plight and the soul of another human being.

The Spine

The Lulav represents the “Jewish spine.” This is the spine and sense of confidence and pride represented by Isaac who with an upright posture walked to the altar and allowed himself, like the fronds of the palm, to be bound. As Abraham tells him that G-d chose him as an offering, the Torah states, “they walked together.” Isaac continues to walk upright. He does not duck, bend, or run.

Isaac bequeathed that “spine,” the Lulav, to us—the ability for us to make sacrifices for truth, for G-d, for Yiddishkeit, with vigor, pride, dignity and unwavering resolve. We need not apologize for being Jewish, and become defensive, meek, bent, or repressed. We carry our Jewishness with full confidence and dignity. We stand erect. We are capable of standing up for our people and our faith with pride and full stature.

A King in Dachau