A Community Never Dies

Is It Not Insensitive to Interrupt Shivah for a Holiday?

- June 9, 2016

- |

- 3 Sivan 5776

Rabbi YY Jacobson

3651 views

Kantonists

A Community Never Dies

Is It Not Insensitive to Interrupt Shivah for a Holiday?

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- June 9, 2016

Interruption of Shivah

A teaching in the Mishna defines the duties of a Jew who is in mourning at the outset of a festival. “Regalim mafsikim,” state the sages, “festivals interrupt shivah,” the seven-day period of mourning following the death and burial of a close relative (Moed Katan 3:5).

In one of the most brilliant psychological responses to death, mourners, in the Jewish tradition, are supposed to step out of normal life when they have suffered the loss of a loved one. They don’t pretend to be brave and go on as if nothing had happened. They take time to grieve; their normal pattern of behavior is disrupted as a way of recognizing that a profound change has occurred in their life. Thus the custom is that they stay home during shivah, and people come to be with them, to share in their grief. Jewish law recognized that life will never be the same again, and the dramatic transition requires time off.

But the Mishna is saying that if one of the major Jewish festivals (Shavuos, Passover, or Sukkos) begins while you are in the shivah period you are supposed to put aside shivah and join with the community in celebrating the festival. So for example, if someone lost a loved one on Sunday and buried them on Monday, Shivah would only go till Saturday night, when Shavuos begins. The mourner takes part in a Shavuos celebration, attends a Passover seder, goes out to eat in the Sukkah, etc.

Why? At first glance this law seems insensitive. Seeing how sensitive Jewish law is to someone who suffered a loss, requiring them to stay home for seven days, why suddenly in this case do we display such brute insensitivity? How can we be expected to put aside our grief and go to a celebration? How can halacha command us to suppress natural human emotions for the sake of going through the motions of a ritual?

The Talmud, the commentary on the Mishna, explains the reason for this ruling: “aseh d’rabim” – a positive mitzvah incumbent on the community, overrides “aseh d’yachid” – a positive mitzvahincumbent on the individual” (Talmud Moed Katan 14b). Celebration of the festivals is a mitzvah of the entire community; mourning is a mitzvah on the individual who suffered the loss. The communal time of joy overrides the individual’s time of grief.

But this does not seem to answer the question. After all, if someone lost a loved one, how do we ask of them to transcend their individual state of mourning because of the communal state of joy? Let the community celebrate, but let the individual mourn!

If I Am Only For Myself…

Each and every Jew can experience himself or herself in one of two ways, and they are both equally true. We are individuals. Each of us has our own “pekel,” our own baggage, our own unique story and narrative. I got my issues, you got yours; I got my life, you got yours. You fend for yourself, I fend for myself. In the words of Hillel: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”

Together with this, we are each also an indispensable part of “klal Yisroel,” of the community of Israel. We are not only individuals; we are also an integral part of “keneset Yisroel,” the collective soul of the Jewish people. Like limbs in a body, each limb has its own individual character and chemistry, but it is also a part of a single organism we call the human body.

The difference between these two components is critical. The individual life can die. But, in the words of the Talmud, “tzebor lo mas,” the community does not die (Talmud Horayos 6a). The collective body we call “the Jewish people” never dies, it only changes hands. The very same “body” of “klal Yisroel” that existed 3000 years ago still exists today. Moses was a Jew and you are a Jew. Rabbi Akiva was a Jew and you are a Jew. The Ball Shem Tov was a Jew and you are a Jew. An individual can die; a nation does not die (unless the entire nation is obliterated.) Again in the words of Hilel: “But if I am only for myself, what am I?”

The tyrants and Anti-Semites in history could sadly wipe put individual Jews, but never the Jewish people. “Tzebor lo mas.” The community of Israel never dies.

Eternity

Now we will understand the explanation of the Talmud, that shivah gets interrupted for a holiday because the mitzvah of the community takes precedent over the mitzvah of the individual. This is not saying that the individual who suffered a loss must forget about his or her own pain because the community is celebrating. That would be unfair. Rather the Talmud is telling us something deeper.

When the community of Israel is experiencing a celebration, a festival, marking a watershed moment in the history of our people—that celebration of the “tzebur,” of the collective body of the Jewish people, includes also the person who passed away, because that aspect of us which is part of the community of Israel never ever dies. The “Jew” in the Jew cannot die, because it lives on in the collective body of the Jewish nation.

When the mourner interrupts his shivah to celebrate the holiday of Passover, Shavuos or Sukkos, he is not diverting his heart from his or her beloved one; rather he is given the ability to connect to the central defining moments defining Jewish history and eternity, and it is in that drama that his loved one still lives on. In the collective life of the Jewish people, and in our collective celebrations of Jewish faith and history, our loved ones continue to live.

A Lost Child

This may be of the reasons we recite Yizkor on each of the three holidays. During Yizkor, we don’t only remember our loved ones who passed on; we also ensure that a part of them never dies, by insuring that the collective organism of Am Yisroel—the people of Israel—survives and thrives.

A moving story is told by the Yiddish writer Shalom Asch, about an elderly Jewish couple in Russia forced by the government to house a soldier in their home. They move out of their bedroom, and the young man, all gruffness and glares, moves in with his pack, rifle and bedroll. It's Friday night, and the couple prepares to sit down for Shabbat dinner. The soldier takes his place at the table. Only now is it apparent just how young he is. He sits and stares with wide eyes as the old woman kindles the Shabbas candles. And he listens as the old man chants the Kiddush and Hamotzie. He quickly devours the hunk of challah placed before him, and speaking for the first time, he asks for more. His face is a picture of bewilderment. Something about this scene -- the candles, the chant, the taste of the challah, captures him. It touches him in some mysterious way.

He rises from his seat at the table, and beckons the old man to follow him, back into the bedroom. He pulls his heavy pack from the floor onto the bed, and begins to pull things out. Uniforms, equipment, ammunition. Until finally, at the very bottom, he pulls out a small velvet bag, tied with a drawstring. "Can you tell me, perhaps, what this is?" he asks the old man, with eyes suddenly gentle and imploring.

The old man, takes the bag in trembling fingers and opens the string. Inside is a child's tallis, a tiny set of tefillin, and small book of Hebrew prayers.

"Where did you get this?" he asks the soldier.

"I have always had it...I don't remember when..."

The old man opens the prayer book, and reads the inscription, his eyes filling with tears:

“To our son, Yossel, taken from us as a boy, should you ever see your Bar Mitzvah, know that your mama and tata always love you.”

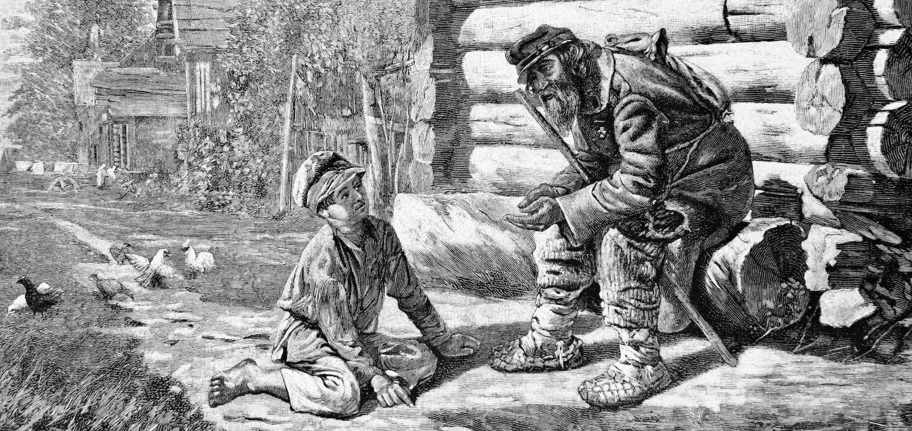

You see, this boy was one of the cantonists. On August 26, 1827, Tsar Nicholas published the Recruitment Decree calling for conscription of Jewish boys between the ages of twelve and twenty-five into the Russian army. These boys were known as Cantonists; derived from the term 'Canton' referring to the 'districts' they were sent, and the 'barracks' in which they were kept. Conscripts under the age of eighteen were assigned to live in preparatory institutions until they were old enough to formally join the army. The twenty-five years of service required that these recruits be counted from age eighteen, even if they had already spent many years in military institutions before reaching that age.

Nicholas strengthened the Cantonist system and used it to single out Jewish children for persecution, their baptism being of a high priority to him. No other group or minority in Russia was expected to serve at such a young age, nor were other groups of recruits tormented in the same way. Nicholas wrote in a confidential memorandum, "The chief benefit to be derived from the drafting of the Jews is the certainty that it will move them most effectively to change their religion."

During the reign of Nicholas I, approximately seventy thousand Jews, some fifty thousand who were children, were taken by force from their homes and families and inducted into the Russian army. The boys, raised in the traditional world of the Shtetle, were pressured via every possible means, including torture, to accept baptism. Many resisted and some managed to maintain their Jewish identity. The magnitude of their struggle is difficult to conceive.

This thirty-year period from 1827 till 1856 saw the Jewish community in an unrelieved state of panic. Parents lived in perpetual fear that their children would be the next to fill the Tsar's quota. A child could be snatched from any place at any time. Every moment might be the last together; when a child left for cheder (school) in the morning, parents did not know if they would ever see him again. When they retired at night after singing him to sleep, they never knew whether they would have to struggle with the chappers (kidnapper, chap is the Yiddish term for grab) during the night in a last ditch effort to hold onto their son.

These kids were beaten and lashed, often with whips fashioned from their own confiscated tefillin (phylacteries.) In their malnourished states, the open wounds on their chests and backs would turn septic and many boys, who had heroically resisted renouncing their Judaism for months, would either perish or cave in and consent to the show of baptism. As kosher food was unavailable, they were faced with the choice of either abandoning Jewish dietary laws or starvation. To avoid this horrific fate, some parents actually had their sons' limbs amputated in the forests at the hands of local blacksmiths, and their sons—no longer able bodied—would avoid conscription. Other children committed suicide rather than convert.

All cantonists were institutionally underfed, and encouraged to steal food from the local population, in emulation of the Spartan character building. (On one occasion in 1856 a Jewish cantonist Khodulevich managed to steal the Tsar's watch during military games at Uman. Not only was he not punished, but he was given a reward of 25 rubles for his display of prowess.)

This boy in our story was one of those cantonists.

Let Them Live

At Yizkor, our mama and tata, our zeide and babe, our great grandparents for many generations, whisper to us how deeply they love us and believe in us. No matter how many years have passed, the bond is eternal and timeless.

And when we embrace and continue their story, we ensure that every single Jew who ever walked the face of this earth is still, in some very real way, alive.

- Comment

Class Summary:

It seems like an insensitive law: If one of the major Jewish festivals begins while you are in the shivah period, you are supposed to put aside shivah and join with the community in celebrating the festival. But how can we be expected to put aside our grief and go to a celebration? How can halacha command us to suppress natural human emotions for the sake of going through the motions of a ritual?

There are two dimensions existing in every Jew, one that dies, and one that can never die. On Yizkor, we connect to that part of our loved ones which never dies. On yizkor, we ensure that every Jew who ever walked the face of the earth, remains alive in some very real way.

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein in honor of Sholom Yosef Gavriel ben Maya Tifcha, Gavriel Nash

Interruption of Shivah

A teaching in the Mishna defines the duties of a Jew who is in mourning at the outset of a festival. “Regalim mafsikim,” state the sages, “festivals interrupt shivah,” the seven-day period of mourning following the death and burial of a close relative (Moed Katan 3:5).

In one of the most brilliant psychological responses to death, mourners, in the Jewish tradition, are supposed to step out of normal life when they have suffered the loss of a loved one. They don’t pretend to be brave and go on as if nothing had happened. They take time to grieve; their normal pattern of behavior is disrupted as a way of recognizing that a profound change has occurred in their life. Thus the custom is that they stay home during shivah, and people come to be with them, to share in their grief. Jewish law recognized that life will never be the same again, and the dramatic transition requires time off.

But the Mishna is saying that if one of the major Jewish festivals (Shavuos, Passover, or Sukkos) begins while you are in the shivah period you are supposed to put aside shivah and join with the community in celebrating the festival. So for example, if someone lost a loved one on Sunday and buried them on Monday, Shivah would only go till Saturday night, when Shavuos begins. The mourner takes part in a Shavuos celebration, attends a Passover seder, goes out to eat in the Sukkah, etc.

Why? At first glance this law seems insensitive. Seeing how sensitive Jewish law is to someone who suffered a loss, requiring them to stay home for seven days, why suddenly in this case do we display such brute insensitivity? How can we be expected to put aside our grief and go to a celebration? How can halacha command us to suppress natural human emotions for the sake of going through the motions of a ritual?

The Talmud, the commentary on the Mishna, explains the reason for this ruling: “aseh d’rabim” – a positive mitzvah incumbent on the community, overrides “aseh d’yachid” – a positive mitzvahincumbent on the individual” (Talmud Moed Katan 14b). Celebration of the festivals is a mitzvah of the entire community; mourning is a mitzvah on the individual who suffered the loss. The communal time of joy overrides the individual’s time of grief.

But this does not seem to answer the question. After all, if someone lost a loved one, how do we ask of them to transcend their individual state of mourning because of the communal state of joy? Let the community celebrate, but let the individual mourn!

If I Am Only For Myself…

Each and every Jew can experience himself or herself in one of two ways, and they are both equally true. We are individuals. Each of us has our own “pekel,” our own baggage, our own unique story and narrative. I got my issues, you got yours; I got my life, you got yours. You fend for yourself, I fend for myself. In the words of Hillel: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”

Together with this, we are each also an indispensable part of “klal Yisroel,” of the community of Israel. We are not only individuals; we are also an integral part of “keneset Yisroel,” the collective soul of the Jewish people. Like limbs in a body, each limb has its own individual character and chemistry, but it is also a part of a single organism we call the human body.

The difference between these two components is critical. The individual life can die. But, in the words of the Talmud, “tzebor lo mas,” the community does not die (Talmud Horayos 6a). The collective body we call “the Jewish people” never dies, it only changes hands. The very same “body” of “klal Yisroel” that existed 3000 years ago still exists today. Moses was a Jew and you are a Jew. Rabbi Akiva was a Jew and you are a Jew. The Ball Shem Tov was a Jew and you are a Jew. An individual can die; a nation does not die (unless the entire nation is obliterated.) Again in the words of Hilel: “But if I am only for myself, what am I?”

The tyrants and Anti-Semites in history could sadly wipe put individual Jews, but never the Jewish people. “Tzebor lo mas.” The community of Israel never dies.

Eternity

Now we will understand the explanation of the Talmud, that shivah gets interrupted for a holiday because the mitzvah of the community takes precedent over the mitzvah of the individual. This is not saying that the individual who suffered a loss must forget about his or her own pain because the community is celebrating. That would be unfair. Rather the Talmud is telling us something deeper.

When the community of Israel is experiencing a celebration, a festival, marking a watershed moment in the history of our people—that celebration of the “tzebur,” of the collective body of the Jewish people, includes also the person who passed away, because that aspect of us which is part of the community of Israel never ever dies. The “Jew” in the Jew cannot die, because it lives on in the collective body of the Jewish nation.

When the mourner interrupts his shivah to celebrate the holiday of Passover, Shavuos or Sukkos, he is not diverting his heart from his or her beloved one; rather he is given the ability to connect to the central defining moments defining Jewish history and eternity, and it is in that drama that his loved one still lives on. In the collective life of the Jewish people, and in our collective celebrations of Jewish faith and history, our loved ones continue to live.

A Lost Child

This may be of the reasons we recite Yizkor on each of the three holidays. During Yizkor, we don’t only remember our loved ones who passed on; we also ensure that a part of them never dies, by insuring that the collective organism of Am Yisroel—the people of Israel—survives and thrives.

A moving story is told by the Yiddish writer Shalom Asch, about an elderly Jewish couple in Russia forced by the government to house a soldier in their home. They move out of their bedroom, and the young man, all gruffness and glares, moves in with his pack, rifle and bedroll. It's Friday night, and the couple prepares to sit down for Shabbat dinner. The soldier takes his place at the table. Only now is it apparent just how young he is. He sits and stares with wide eyes as the old woman kindles the Shabbas candles. And he listens as the old man chants the Kiddush and Hamotzie. He quickly devours the hunk of challah placed before him, and speaking for the first time, he asks for more. His face is a picture of bewilderment. Something about this scene -- the candles, the chant, the taste of the challah, captures him. It touches him in some mysterious way.

He rises from his seat at the table, and beckons the old man to follow him, back into the bedroom. He pulls his heavy pack from the floor onto the bed, and begins to pull things out. Uniforms, equipment, ammunition. Until finally, at the very bottom, he pulls out a small velvet bag, tied with a drawstring. "Can you tell me, perhaps, what this is?" he asks the old man, with eyes suddenly gentle and imploring.

The old man, takes the bag in trembling fingers and opens the string. Inside is a child's tallis, a tiny set of tefillin, and small book of Hebrew prayers.

"Where did you get this?" he asks the soldier.

"I have always had it...I don't remember when..."

The old man opens the prayer book, and reads the inscription, his eyes filling with tears:

“To our son, Yossel, taken from us as a boy, should you ever see your Bar Mitzvah, know that your mama and tata always love you.”

You see, this boy was one of the cantonists. On August 26, 1827, Tsar Nicholas published the Recruitment Decree calling for conscription of Jewish boys between the ages of twelve and twenty-five into the Russian army. These boys were known as Cantonists; derived from the term 'Canton' referring to the 'districts' they were sent, and the 'barracks' in which they were kept. Conscripts under the age of eighteen were assigned to live in preparatory institutions until they were old enough to formally join the army. The twenty-five years of service required that these recruits be counted from age eighteen, even if they had already spent many years in military institutions before reaching that age.

Nicholas strengthened the Cantonist system and used it to single out Jewish children for persecution, their baptism being of a high priority to him. No other group or minority in Russia was expected to serve at such a young age, nor were other groups of recruits tormented in the same way. Nicholas wrote in a confidential memorandum, "The chief benefit to be derived from the drafting of the Jews is the certainty that it will move them most effectively to change their religion."

During the reign of Nicholas I, approximately seventy thousand Jews, some fifty thousand who were children, were taken by force from their homes and families and inducted into the Russian army. The boys, raised in the traditional world of the Shtetle, were pressured via every possible means, including torture, to accept baptism. Many resisted and some managed to maintain their Jewish identity. The magnitude of their struggle is difficult to conceive.

This thirty-year period from 1827 till 1856 saw the Jewish community in an unrelieved state of panic. Parents lived in perpetual fear that their children would be the next to fill the Tsar's quota. A child could be snatched from any place at any time. Every moment might be the last together; when a child left for cheder (school) in the morning, parents did not know if they would ever see him again. When they retired at night after singing him to sleep, they never knew whether they would have to struggle with the chappers (kidnapper, chap is the Yiddish term for grab) during the night in a last ditch effort to hold onto their son.

These kids were beaten and lashed, often with whips fashioned from their own confiscated tefillin (phylacteries.) In their malnourished states, the open wounds on their chests and backs would turn septic and many boys, who had heroically resisted renouncing their Judaism for months, would either perish or cave in and consent to the show of baptism. As kosher food was unavailable, they were faced with the choice of either abandoning Jewish dietary laws or starvation. To avoid this horrific fate, some parents actually had their sons' limbs amputated in the forests at the hands of local blacksmiths, and their sons—no longer able bodied—would avoid conscription. Other children committed suicide rather than convert.

All cantonists were institutionally underfed, and encouraged to steal food from the local population, in emulation of the Spartan character building. (On one occasion in 1856 a Jewish cantonist Khodulevich managed to steal the Tsar's watch during military games at Uman. Not only was he not punished, but he was given a reward of 25 rubles for his display of prowess.)

This boy in our story was one of those cantonists.

Let Them Live

At Yizkor, our mama and tata, our zeide and babe, our great grandparents for many generations, whisper to us how deeply they love us and believe in us. No matter how many years have passed, the bond is eternal and timeless.

And when we embrace and continue their story, we ensure that every single Jew who ever walked the face of this earth is still, in some very real way, alive.

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- June 9, 2016

- |

- 3 Sivan 5776

- |

- 3651 views

A Community Never Dies

Is It Not Insensitive to Interrupt Shivah for a Holiday?

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- June 9, 2016

Interruption of Shivah

A teaching in the Mishna defines the duties of a Jew who is in mourning at the outset of a festival. “Regalim mafsikim,” state the sages, “festivals interrupt shivah,” the seven-day period of mourning following the death and burial of a close relative (Moed Katan 3:5).

In one of the most brilliant psychological responses to death, mourners, in the Jewish tradition, are supposed to step out of normal life when they have suffered the loss of a loved one. They don’t pretend to be brave and go on as if nothing had happened. They take time to grieve; their normal pattern of behavior is disrupted as a way of recognizing that a profound change has occurred in their life. Thus the custom is that they stay home during shivah, and people come to be with them, to share in their grief. Jewish law recognized that life will never be the same again, and the dramatic transition requires time off.

But the Mishna is saying that if one of the major Jewish festivals (Shavuos, Passover, or Sukkos) begins while you are in the shivah period you are supposed to put aside shivah and join with the community in celebrating the festival. So for example, if someone lost a loved one on Sunday and buried them on Monday, Shivah would only go till Saturday night, when Shavuos begins. The mourner takes part in a Shavuos celebration, attends a Passover seder, goes out to eat in the Sukkah, etc.

Why? At first glance this law seems insensitive. Seeing how sensitive Jewish law is to someone who suffered a loss, requiring them to stay home for seven days, why suddenly in this case do we display such brute insensitivity? How can we be expected to put aside our grief and go to a celebration? How can halacha command us to suppress natural human emotions for the sake of going through the motions of a ritual?

The Talmud, the commentary on the Mishna, explains the reason for this ruling: “aseh d’rabim” – a positive mitzvah incumbent on the community, overrides “aseh d’yachid” – a positive mitzvahincumbent on the individual” (Talmud Moed Katan 14b). Celebration of the festivals is a mitzvah of the entire community; mourning is a mitzvah on the individual who suffered the loss. The communal time of joy overrides the individual’s time of grief.

But this does not seem to answer the question. After all, if someone lost a loved one, how do we ask of them to transcend their individual state of mourning because of the communal state of joy? Let the community celebrate, but let the individual mourn!

If I Am Only For Myself…

Each and every Jew can experience himself or herself in one of two ways, and they are both equally true. We are individuals. Each of us has our own “pekel,” our own baggage, our own unique story and narrative. I got my issues, you got yours; I got my life, you got yours. You fend for yourself, I fend for myself. In the words of Hillel: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”

Together with this, we are each also an indispensable part of “klal Yisroel,” of the community of Israel. We are not only individuals; we are also an integral part of “keneset Yisroel,” the collective soul of the Jewish people. Like limbs in a body, each limb has its own individual character and chemistry, but it is also a part of a single organism we call the human body.

The difference between these two components is critical. The individual life can die. But, in the words of the Talmud, “tzebor lo mas,” the community does not die (Talmud Horayos 6a). The collective body we call “the Jewish people” never dies, it only changes hands. The very same “body” of “klal Yisroel” that existed 3000 years ago still exists today. Moses was a Jew and you are a Jew. Rabbi Akiva was a Jew and you are a Jew. The Ball Shem Tov was a Jew and you are a Jew. An individual can die; a nation does not die (unless the entire nation is obliterated.) Again in the words of Hilel: “But if I am only for myself, what am I?”

The tyrants and Anti-Semites in history could sadly wipe put individual Jews, but never the Jewish people. “Tzebor lo mas.” The community of Israel never dies.

Eternity

Now we will understand the explanation of the Talmud, that shivah gets interrupted for a holiday because the mitzvah of the community takes precedent over the mitzvah of the individual. This is not saying that the individual who suffered a loss must forget about his or her own pain because the community is celebrating. That would be unfair. Rather the Talmud is telling us something deeper.

When the community of Israel is experiencing a celebration, a festival, marking a watershed moment in the history of our people—that celebration of the “tzebur,” of the collective body of the Jewish people, includes also the person who passed away, because that aspect of us which is part of the community of Israel never ever dies. The “Jew” in the Jew cannot die, because it lives on in the collective body of the Jewish nation.

When the mourner interrupts his shivah to celebrate the holiday of Passover, Shavuos or Sukkos, he is not diverting his heart from his or her beloved one; rather he is given the ability to connect to the central defining moments defining Jewish history and eternity, and it is in that drama that his loved one still lives on. In the collective life of the Jewish people, and in our collective celebrations of Jewish faith and history, our loved ones continue to live.

A Lost Child

This may be of the reasons we recite Yizkor on each of the three holidays. During Yizkor, we don’t only remember our loved ones who passed on; we also ensure that a part of them never dies, by insuring that the collective organism of Am Yisroel—the people of Israel—survives and thrives.

A moving story is told by the Yiddish writer Shalom Asch, about an elderly Jewish couple in Russia forced by the government to house a soldier in their home. They move out of their bedroom, and the young man, all gruffness and glares, moves in with his pack, rifle and bedroll. It's Friday night, and the couple prepares to sit down for Shabbat dinner. The soldier takes his place at the table. Only now is it apparent just how young he is. He sits and stares with wide eyes as the old woman kindles the Shabbas candles. And he listens as the old man chants the Kiddush and Hamotzie. He quickly devours the hunk of challah placed before him, and speaking for the first time, he asks for more. His face is a picture of bewilderment. Something about this scene -- the candles, the chant, the taste of the challah, captures him. It touches him in some mysterious way.

He rises from his seat at the table, and beckons the old man to follow him, back into the bedroom. He pulls his heavy pack from the floor onto the bed, and begins to pull things out. Uniforms, equipment, ammunition. Until finally, at the very bottom, he pulls out a small velvet bag, tied with a drawstring. "Can you tell me, perhaps, what this is?" he asks the old man, with eyes suddenly gentle and imploring.

The old man, takes the bag in trembling fingers and opens the string. Inside is a child's tallis, a tiny set of tefillin, and small book of Hebrew prayers.

"Where did you get this?" he asks the soldier.

"I have always had it...I don't remember when..."

The old man opens the prayer book, and reads the inscription, his eyes filling with tears:

“To our son, Yossel, taken from us as a boy, should you ever see your Bar Mitzvah, know that your mama and tata always love you.”

You see, this boy was one of the cantonists. On August 26, 1827, Tsar Nicholas published the Recruitment Decree calling for conscription of Jewish boys between the ages of twelve and twenty-five into the Russian army. These boys were known as Cantonists; derived from the term 'Canton' referring to the 'districts' they were sent, and the 'barracks' in which they were kept. Conscripts under the age of eighteen were assigned to live in preparatory institutions until they were old enough to formally join the army. The twenty-five years of service required that these recruits be counted from age eighteen, even if they had already spent many years in military institutions before reaching that age.

Nicholas strengthened the Cantonist system and used it to single out Jewish children for persecution, their baptism being of a high priority to him. No other group or minority in Russia was expected to serve at such a young age, nor were other groups of recruits tormented in the same way. Nicholas wrote in a confidential memorandum, "The chief benefit to be derived from the drafting of the Jews is the certainty that it will move them most effectively to change their religion."

During the reign of Nicholas I, approximately seventy thousand Jews, some fifty thousand who were children, were taken by force from their homes and families and inducted into the Russian army. The boys, raised in the traditional world of the Shtetle, were pressured via every possible means, including torture, to accept baptism. Many resisted and some managed to maintain their Jewish identity. The magnitude of their struggle is difficult to conceive.

This thirty-year period from 1827 till 1856 saw the Jewish community in an unrelieved state of panic. Parents lived in perpetual fear that their children would be the next to fill the Tsar's quota. A child could be snatched from any place at any time. Every moment might be the last together; when a child left for cheder (school) in the morning, parents did not know if they would ever see him again. When they retired at night after singing him to sleep, they never knew whether they would have to struggle with the chappers (kidnapper, chap is the Yiddish term for grab) during the night in a last ditch effort to hold onto their son.

These kids were beaten and lashed, often with whips fashioned from their own confiscated tefillin (phylacteries.) In their malnourished states, the open wounds on their chests and backs would turn septic and many boys, who had heroically resisted renouncing their Judaism for months, would either perish or cave in and consent to the show of baptism. As kosher food was unavailable, they were faced with the choice of either abandoning Jewish dietary laws or starvation. To avoid this horrific fate, some parents actually had their sons' limbs amputated in the forests at the hands of local blacksmiths, and their sons—no longer able bodied—would avoid conscription. Other children committed suicide rather than convert.

All cantonists were institutionally underfed, and encouraged to steal food from the local population, in emulation of the Spartan character building. (On one occasion in 1856 a Jewish cantonist Khodulevich managed to steal the Tsar's watch during military games at Uman. Not only was he not punished, but he was given a reward of 25 rubles for his display of prowess.)

This boy in our story was one of those cantonists.

Let Them Live

At Yizkor, our mama and tata, our zeide and babe, our great grandparents for many generations, whisper to us how deeply they love us and believe in us. No matter how many years have passed, the bond is eternal and timeless.

And when we embrace and continue their story, we ensure that every single Jew who ever walked the face of this earth is still, in some very real way, alive.

- Comment

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein in honor of Sholom Yosef Gavriel ben Maya Tifcha, Gavriel Nash

Class Summary:

It seems like an insensitive law: If one of the major Jewish festivals begins while you are in the shivah period, you are supposed to put aside shivah and join with the community in celebrating the festival. But how can we be expected to put aside our grief and go to a celebration? How can halacha command us to suppress natural human emotions for the sake of going through the motions of a ritual?

There are two dimensions existing in every Jew, one that dies, and one that can never die. On Yizkor, we connect to that part of our loved ones which never dies. On yizkor, we ensure that every Jew who ever walked the face of the earth, remains alive in some very real way.

Related Classes

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!

cz -4 years ago

yizkor

I live in a community where many immigrants from the former soviet union and Ukraine live. It"s a very interesting phenomenon as the elderly people come to shul on Yom Kippur for yizkor. many of them cannot read Hebrew. but they come (even with their phones as they don't know better)you see their will for connection. I was told by an immigrant how they saved the yizkor page in a recipe book as it was illegal to have anything in Hebrew. yizkor definitely has something powerful in connecting.many of these people will sit for a while as long as they won't miss the tefilla.

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.

sj -8 years ago

So moving so touching. It would have been beautiful to hear it from every Rabbi before Yizkor. Thank you for bringing "Life" into the usually sad ritual.

Reply to this comment.Flag this comment.