It’s a Beautiful Heart

Counting Days and Weeks: Confronting Mental Illness, Trauma, and Depression

- May 16, 2024

- |

- 8 Iyyar 5784

Rabbi YY Jacobson

4958 views

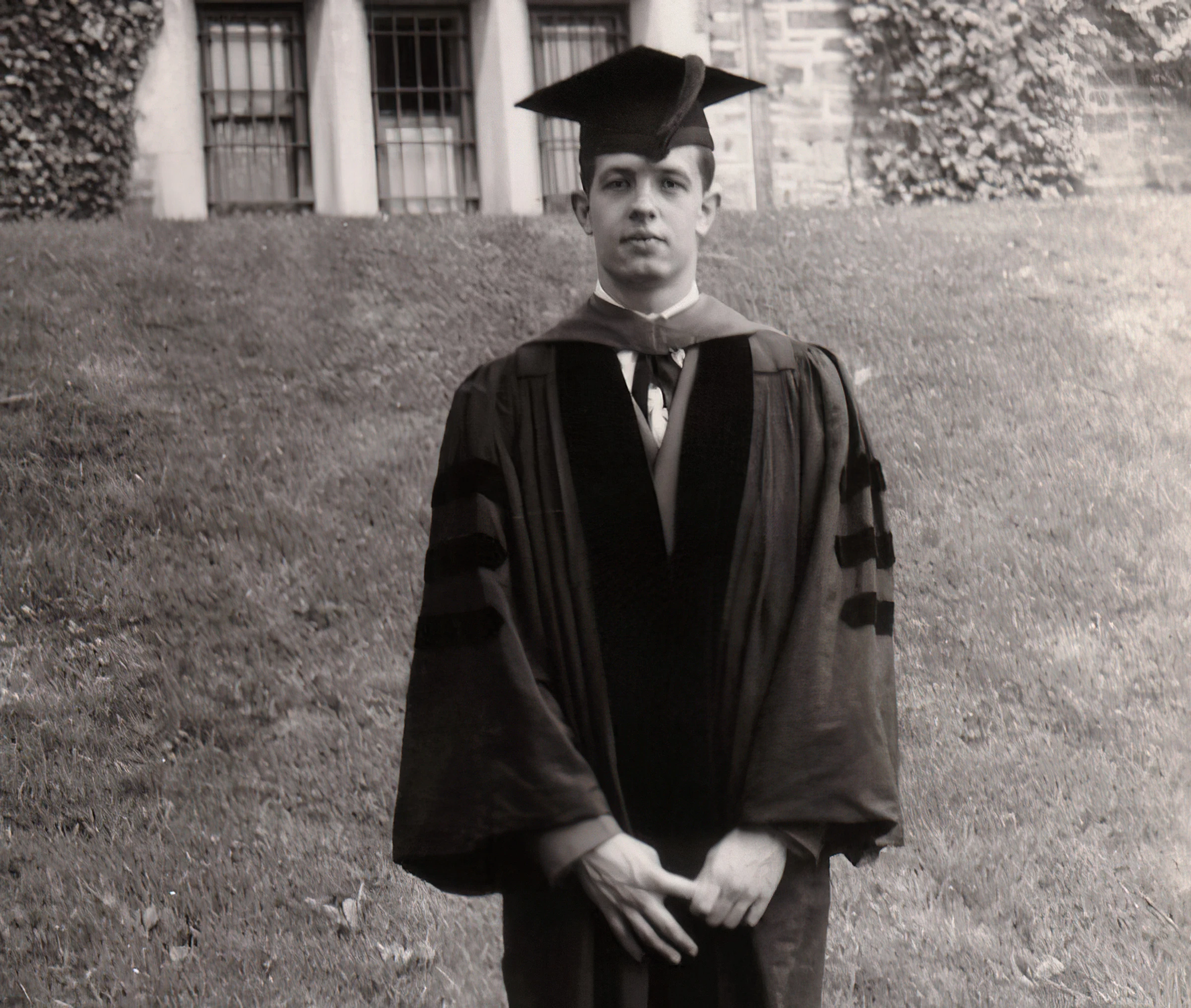

John F. Nash Jr. at his Princeton graduation in 1950

It’s a Beautiful Heart

Counting Days and Weeks: Confronting Mental Illness, Trauma, and Depression

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 16, 2024

Counting Days and Weeks

There are three kinds of people, goes the old joke: those who can count and those who can’t.

There is something strange about the way we count ‘sefirah’—the 49-day count, in the Jewish tradition, between Passover and the festival of Shavuos.

The Talmud states:[1]

Abaye stated, "It is a Mitzvah to count the days, and it is a Mitzvah to count the weeks.” This is because both are mentioned explicitly in the Torah:

Leviticus 23:15-16: From the day following the (first) rest day (of Pesach)—the day you bring the Omer as a wave-offering—you should count for yourselves seven weeks. (When you count them) they should be perfect. You should count until (but not including) fifty days, (i.e.) the day following the seventh week. (On the fiftieth day) you should bring (the first) meal-offering (from the) new (crop) to G-d.

Deuteronomy 16:9-10: You shall count seven weeks for yourself; from [the time] the sickle is first put to the standing crop, you shall begin to count seven weeks. And you shall perform the Festival of Weeks to the Lord, your God, the donation you can afford to give, according to how the Lord, your God, shall bless you.

Clearly, the Torah talks about two forms of counting: counting seven weeks and counting 49 days. We thus fulfill both mandates: At the conclusion of the first week, we count as follows: “Today is seven days, which is one week to the Omer.” The next night, we count as follows: “Today is eight days, which is one week and one day to the Omer.” “Today is forty-eight days, which is six weeks and six days to the Omer.”

Yet this is strange. Why is the Torah adamant that we count both the days and the weeks simultaneously? One of these counts is superfluous. What do we gain by counting the week after counting the days? Either say simply: “Today is seven days to the Omer,” and if you want to know how many weeks that is, you can do the math yourself, or alternatively, stick to weeks: “Today is one week to the Omer,” and you don’t have to be a genius to know how many days that includes!

Biblical or Rabbinic?

There is yet another perplexing matter.

The “Karban Omer” was a barley offering brought to the Holy Temple on the second day of Passover (on the 16th of Nissan). They would harvest barley, grind it to flour, and offer a fistful of the flour on the altar. The rest of the flour would be baked as matzah and eaten by the Kohanim (Omer is the Hebrew name for the volume of flour prepared; it is the volume of 42.2 eggs).

Hence, the Torah states:[2] “And you shall count for yourselves from the morrow of the Sabbath, from the day on which you bring the Omer offering, seven complete weeks shall there be ,until the morrow of the seventh week you shall count fifty days...”

When the Beis HaMikdash (Holy Temple) stood in Jerusalem, this offering of a measure (omer) of barley, brought on the second day of Passover, marked the commencement of the seven-week count. Today, we lack the opportunity to bring the Omer offering on Passover. The question then arises, is there still a mandate to do the sefirat haomer, the counting of the Omer? Without the Omer, are we still obligated to count the seven-week period?

As you may have guessed, there is a dispute among our sages.

שולחן ערוך הרב אורח חיים סימן תפט סעיף ב: ומצוה זו נוהגת בארץ ובחו"ל בפני הבית ושלא בפני הבית. ויש אומרים שבזמן הזה שאין בית המקדש קיים ואין מקריבין העומר אין מצוה זו נוהגת כלל מדברי תורה אלא מדברי סופרים שתיקנו זכר למקדש וכן עיקר.

The Rambam (Maimonides), the Chinuch, the Ravya, and others believe that the mandate to count isn’t dependent on the Omer offering. Even today, we are obligated biblically to count 49 days between Passover and Shavuos.

However, Tosefot and most halachic authorities, including the Code of Jewish Law,[3] maintain the view that the biblical mitzvah of counting directly depends on the actual Omer offering. Hence, today, there is only a rabbinic obligation to count, to commemorate the counting in the time of the Holy Temple. Our counting today is not a full-fledged biblical commandment (mitzvah deoraita) but a rabbinical ordinance that merely commemorates the mitzvah fulfilled in the times of the Beit HaMikdash.

So far so good.

The Third Opinion

But there is a fascinating third and lone opinion, that of the 13th-century French and Spanish sage Rabbeinu Yerucham.[4]

רבינו ירוחם ספר תולדות אדם וחוה, חלק אדם, נתיב ה חלק ד: ונראה לן, משום דכתוב בתורה [שתי פרשיות], שבעה שבועות תספור לך וגו׳ וכתיב נמי מיום הביאכם את עומר וגו׳ שבע שבתות תמימות תהיין, נמצא שלא נכתבה ספירת שבועות כי אם גבי העומר, אבל ספירת הימים [תספרו חמשים יום] לא כתיב גבי עומר, נמצא דספירת הימים הוא מן התורה אפילו בזמן הזה, וספירת השבועות בזמן דאיכא עומר. והיו מברכים זה על זה בזמן שביהמ"ק היה קיים... ובזמן הזה אנו סופרים לשבועות זכר למקדש... לכך אנו אומרים שהם כך וכך שבועות שאין זו ספירה ממש.

He says that it depends which counting we are talking about. The days or the weeks. The counting of the days is a biblical mandate even today, while the counting of the weeks, says Rabbeinu Yerucham, is only a rabbinic mandate.

This third opinion is an interesting combination of the first two: According to Rabbeinu Yerucham, it is a biblical mitzvah to count the days even when the Beit HaMikdash is not extant, but the mitzvah to count the weeks applies only when the Omer is offered and is thus today only a rabbinical commandment.

The rationale behind his view is fascinating. When the Torah states to count the weeks, it is stated in context of the Omer offering; so, without the omer offering, the biblical obligation falls away. But when the Torah states to count the days, it says so independently of the Omer offering. So even without an omer, there is still a mitzvah to count 49 days.

Now this seems really strange. How are we to understand Rabbeinu Yerucham? Counting is counting, what exactly is the difference between saying “Today is twenty-eight days of the Omer” and saying “Today is four weeks of the Omer”? How can we make sense of the notion that counting days is a biblical mandate while counting weeks is a rabbinic mandate?

To be sure, he offers a convincing proof from the Torah text. But that only transfers the question onto the Torah: What would be the logic to command Jews today, in exile, to count only days and not weeks? Yet Jews during the time of the Holy Temple were commanded by the Torah to do both?

The views of Rambam and Tosefos are clear. Either the entire obligation (the count of the days and the weeks) is biblical, or it is all rabbinic. But the split Rabbanu Yerucham suggests seems enigmatic. Why would the Torah make this differentiation? Why would it deny us the opportunity to count weeks during exile, but still obligate us to count days lacking the Holy Temple?

Two Types of Self-Work

Let’s excavate the mystery of the days and the weeks and the three views of Rambam, Tosefos and Rabanu Yerucham, from the deeper emotional, psychological and spiritual vantage point. This explanation was offered by the Lubavitcher Rebbe during an address, on Lag B’Omer 5711, May 24, 1951.[5]

The teachings of Kabbalah and Chassidism describe seven basic character traits in the heart of each human being: Chesed (love, kindness), Gevurah (discipline, boundaries, restraint), Tiferet (beauty, empathy), Netzach (victory, ambition), Hod (humility, gratitude, and acknowledging mistakes), Yesod (bonding and communicatively) and Malchus (leadership, confidence, selflessness).

This is the deeper significance of the “counting of the omer,” the mitzvah to count seven weeks from Passover to Shavuot. Judaism designates a period of the year for “communal therapy,” when together we go through a process of healing our inner selves, step by step, issue by issue, emotion by emotion. For each of the seven weeks, we focus on one of the seven emotions in our lives, examining it, refining it, and fixing it—aligning it with the Divine emotions.[6]

In the first week, we focus on the love in our lives. Do I know how to express and receive love? Do I know how to love? In the second week, we focus on our capacity for creating boundaries. Do I know how to create and maintain proper borders? In the third week, we reflect on our ability to empathize. Do I know how to emphasize? Do I know how to be here for someone else on their terms, not mine? In the fourth week, we look at our capacity to triumph in the face of adversity. Do I know how to win? Do I have ambition? The fifth week is focused on our ability to express gratitude, show vulnerability, and admit mistakes. The sixth week—on our ability to communicate and bond. And finally, in the seventh week, we focus on our skills as leaders. I’m I confident enough to lead? Do I know how to lead? Do I possess inner dignity? Is my leadership driven by insecurity or egotism? I’m I king over myself? Do I possess inner core self-value?

But as we recall, the mitzvah is to count both the days and the weeks. For each of the seven weeks is further divided into seven days. These seven traits are expressed in our life in various thoughts, words and deeds. So during the seven days of each week, we focus each day on another detail of how this particular emotion expresses itself in our lives. If the week-count represents tackling the core of the emotion itself, the day-count represents tackling not the emotion itself, but rather how it expresses itself in our daily lives, in the details of our lives, in our behaviors, words and thoughts.[7]

Transformation vs. Self-Control

When I say, “Today is one week to the omer,” I am saying that today, I managed to tune in to the full scope of that emotion, transforming it and healing it at its core.

Every once in a while, you hear what we call a wonderous journey of incredible healing and transformation. Someone who was struggling with a trauma or an addiction for many years, uncovers a deep awareness, or perhaps goes through a profound healing journey, or a therapeutic program, and they come out completely healed. They have touched such a deep place within themselves, that it completely transformed their life. The trauma is healed; the addiction is gone. Their anger or jealousy is no longer an issue. Like a child who is being toilet trained, at one point, he stops entertaining the idea of using a diaper. He has matured. So too, there is a possibility of counting weeks i.e. completely transforming a particular emotion, completely weeding out the distortions.

The Day Model

But that is a unique experience. And even when it occurs, it may not last forever, or we may still vacillate back to our old coping mechanisms caused by our traumas. We now come to the second model of self-refinement, the “day model.” This is the model that belongs to each of us at every moment. I am not always capable of the week-model, but I am always capable of the day-model. There is no great transformation here, the urges are there, the temptations are there, the dysfunction is there, the addictions are there, the negative emotions are there, and the promiscuous cravings are intact, but I manage to refine the day—meaning I learn how to control where and how that emotion will be expressed in the details of my life. I may not be able to redefine the very core of the emotion—the entire “week”—but I can still choose how it will be channeled, or not channeled, in the details of my life.[8]

Imagine you are driving your car and approaching a red light. Now you've got someone in the backseat screaming, “Go! Run the light! Just do it!” The guy is screaming right in your ear. The screams are loud and annoying, but if you're behind the wheel, no amount of screaming can make you run the light. Why not? Because you can identify the screamer as an alien voice to yourself; he is a stranger bringing up a ludicrous and dangerous idea. You may not be able to stop the screaming, but you can identify it and thus quarantine it, putting it in context of where it belongs—to a strange man hollering stupidity.

But imagine if when hearing that voice “take the red light,” you decide that it is your rational mind speaking to you; you imagine that this is your intelligence speaking to you—then it becomes so much harder to say no.

Same with emotions and thoughts. Even while being emotionally hijacked, I still have the wheel in my hand. I may not have the ability now to transform my urge, and stop the screaming of certain thoughts. Still, as long as I can identify that this thought is not my essence and is coming from a part of me that is insecure and unwholesome, I need not allow that thought to define me and to control my behavior.

Suicidal Thoughts

A woman struggling with suicidal thoughts recently shared with me how she learned to deal with them more effectively.

“I always believed that when I have my suicidal urges, I'm not in control. After all, suicide urges were not something that I could bring up at will - I had to be triggered in a hugely discomforting way for the suicide ideas to surface so vengefully.

“But this time around, I realized that thoughts were just that, thoughts. And it's we who choose if to engage the thoughts and define ourselves by them. We choose to act on our thoughts or not. It's not easy thinking new thoughts when the old familiar thoughts tell you that suicide is the only answer.”

If the only thing people learned was not to be afraid of their experience, that alone would change the world. The moment we can look at our urge or temptation in the eye and say, “Hi! I’m not afraid of you, all you are is a thought,” we have gained control over that urge.

The Text Message

Say you get a text from your wife: “When are you coming home?” Immediately, you experience a thought that produces anger. “Will she ever appreciate how hard I work? What does she think I am doing here in the office? Can’t she just leave me alone!”

But hay, relax. All she asked was when you were coming home, perhaps because she misses you, loves you, and wants to see your face. But due to your own insecurities, you can’t even see that. You are used to your mother bashing you, and you instinctively assume she is also bashing you. But she is not. She just asked a simple, innocent question.

Can I get rid of my insecurity and my anger at the moment? No! But I can IDENTIFY my emotion as coming from my insecure dimensions, and I can say to myself, I will not allow that part of myself to take control over my life. I will not allow the toxic image of myself as the man whom everyone is waiting to criticize to overtake me completely. Once I identify where the emotion comes from, I can quarantine it and let it be what it is, but without allowing it to define me. The key is that I do not get trapped into thinking that that thought is me—that it reflects my essence. No! It is just a thought. It is not me. And it does not have to be me. I define it; it does not define me. It is part of me, but it is not all of me. It is the guy in the back seat screaming, “Take the light.”

I did not manage to refine the week, but I did manage to refine the day—I got control of how my thoughts and emotions manifest themselves in the individual days and behaviors of my life.

Winston Churchill suffered from depression. In his biography, he describes how he came to see his depression as a black dog always accompanying him and sometimes barking very loudly. But the black dog was not him. The depressing thoughts were just that—thoughts.

One of the powerful ideas in Tanya is that thoughts are the “garments of the soul,” not the soul. Garments are made to change. We often see our thoughts as our very selves. But they are not; they are garments. You can change them whenever you want to. [9]

A Beautiful Mind; a Beautiful Life

Several years ago, John Nash, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, was killed with his wife in a devastating car accident in NJ.

It is hard not to shed a tear when you read the biography “A Beautiful Mind” about the tragic and triumphant life of Mr. Nash (later also produced as a film).

John Nash, born in 1928, was named early in his career as one of the most promising mathematicians in the world. Nash is regarded as one of the great mathematicians of the 20th century. He set the foundations of modern game theory— the mathematics of decision-making—while still in his 20s, and his fame grew during his time at Princeton University and at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he met Alicia Larde, a physics major. They married in 1957.

But by the end of the 1950s, insane voices in his head began to overtake his thoughts on mathematical theory. He developed a terrible mental illness. Nash, in his delusions, accused one mathematician of entering his office to steal his ideas and began to hear alien messages. When Nash was offered a prestigious chair at the University of Chicago, he declined because he planned to become Emperor of Antarctica.

John believed that all men who wore red ties were part of a communist conspiracy against him. Nash mailed letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., declaring they were establishing a government. His psychological issues crossed into his professional life when he gave an American Mathematical Society lecture at Columbia University in 1959. While he intended to present proof of the Riemann hypothesis, the lecture was incomprehensible. He spoke as a madman. Colleagues in the audience immediately realized that something was terribly wrong.

He was admitted to the Hospital, where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. For many years he spent periods in psychiatric hospitals, where he received antipsychotic medications and shock therapy.

Due to the stress of dealing with his illness, his wife Alicia divorced him in 1963. And yet Alicia continued to support him throughout his illness. After his final hospital discharge in 1970, he lived in Alicia’s house as a boarder.

It was during this time that he learned how to discard his paranoid delusions consciously. "I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research," Nash later wrote about himself.

He ultimately was allowed by Princeton University to teach again. Over the years, he became a world-renowned mathematician, contributing majorly to the field. In 2001, Alicia decided to marry again her first sweetheart, whom she once divorced. Alicia and John Nash married each other for the second time.

In later years they both became major advocates for mental health care in New Jersey when their son John was also diagnosed with schizophrenia.

In 1994, John Nash won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

What Is Logic?

In the final scene of the film, Nash receives the Nobel Prize. During the ceremony, he says the following:

I've always believed in numbers and the equations and logic that lead to reason.

But after a lifetime of such pursuits, I ask,

"What truly is logic?"

"Who decides reason?"

My quest has taken me through the physical, the metaphysical, the delusional—and back.

And I have made the most important discovery of my career, the most important discovery of my life: It is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logic or reasons can be found.

I'm only here tonight because of you [pointing to his wife, Alicia].

You are the reason I am.

You are all my reasons.

Thank you.

The crowd jumps from their chairs, giving a thundering standing ovation to the brilliant mathematician who has been to hell and back a few times.

And then comes one of the most moving scenes.

Nothing Is Wrong

Right after the Noble Prize ceremony, as John is leaving the hall, the mental disease suddenly attacks him in the most vicious and sinister way. Suddenly, his delusions come right back to him, and in the beautiful hallways of Stockholm, he “sees” the very characters that were responsible for destroying his life. He suddenly “sees” all the communists who he believed were out to destroy him.

It is a potentially tragic moment of epic proportions. Here is a man who just won the Nobel Prize, who has become world-renowned, and who is considered one of the greatest minds of the century. Here is a man standing with his loving wife, basking in the shadow of international glory. And yet, at this very moment, the devil of mental illness strikes lethally, mentally “abducting” poor John Nash.

His wife senses that something is happening; she sees how he has suddenly wandered off. He is not present anymore in the real world. His eyes are elsewhere; his body overtaken by fear.

In deep pain and shock, she turns to her husband and asks him, “What is it? What’s wrong?”

He pauses, looks at the fictional people living in his tormented mind, then looks back at her, and with a smile on his face he says: “Nothing; nothing at all.” He takes her hand and off they go.

It is a moment of profound triumph. Here you have a man at the height of everything, and the schizophrenia suddenly strikes him. There was nothing he could do to get rid of it. It was still there; it never left him. Yet his hard inner world allowed him to identify it as an illness and thus quarantine it. He could define it and place it in context rather than have it define him. He could see it for what it was: an unhealthy mental disease alien to his beautiful essence.

No, he does not get rid of schizophrenia but rather learns how to define it rather than letting it define him. He must be able to at least identify it as thoughts that do not constitute his essence and stem from a part of him that is unhealthy.

John Nash could see all those mental images and say to himself: “These are forces within me; but it is not me. It is a mental illness—and these voices are coming from a part of me that is ill. But I am sitting at the wheel of my life, and I have decided not to allow these thoughts to take over my life. I will continue living, I will continue loving and connecting to my wife and to all the good in my life, even as the devils in my brain never shut up. I can’t count my weeks, but I can count my days.”

Nash once said something very moving about himself. "I wouldn't have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally." He also said, "If I felt completely pressure-less, I don't think I would have gone in this pattern". You see, he managed to even perceive the blessing and the opportunity in his struggle, despite the terrible price he paid for them.

Nash was a hero of real life. Here you have a guy dealing with a terrible mental sickness, but with time, work, and most importantly, with love and support, he learns to stand up to it. He learns how his health isn’t defined by the mental chatter and by what his mind decides to show him now. He has learned that despite all of it, day in and day out, he can show up in his life and be in control, rather than the illness controlling him.

The Accident

On May 23, 2015, John and his wife Alicia were on their way home after a visit to Norway, where Nash had received the Abel Prize for Mathematics from King Harald V for his work.

He did arrange for a limo to pick him and his wife up from Newark airport and take them home to West Windsor, NJ. The plane landed early, so they picked up a regular cab to take them home.

They were both sitting in a cab on the New Jersey Turnpike. When the driver of the taxicab lost control of the vehicle and struck a guardrail. Both John and Alicia were ejected from the car upon impact and died on the spot. Nash was 86 years old; his wife 80.

What Can We Achieve Now?

At last, we can appreciate the depth of the Torah law concerning the counting of the omer. The quest for truth, healing, and perfection continues at all times and under all conditions, even in the darkest hours of exile. Thus, we are instructed to count not only the days but also the weeks. We are charged with the duty of learning self-control (days) and trying to achieve transformation (weeks).[10] But it is here that Rabbeinu Yerucham offers us a deeply comforting thought.

True, in the times of the Holy Temple, a time of great spiritual revelation, the Torah instructs us and empowers us to count both days and weeks. In the presence of such intense spiritual awareness, they also had the ability to count weeks. However today, says Rabbeinu Yerucham, we don’t breathe the same awareness. We are in exile. We live in a spiritually diminished level of awareness. Hence, the biblical obligation is to count the days, to gain control over our behavior. Counting the weeks, i.e. fully transforming our emotions, is only a rabbinic obligation, simply to reminisce and remember that ultimately there is a path of transformation we strive for.[11]

Indeed, as we are living today in the times of redemption, more and more we are experiencing the ability for full healing—transforming our days and our weeks, bidding farewell to our traumas forever.

[1] Menachos 66a

[2] Leviticus 23:15

[3] Tosefos Menachos 66a. Shlchan Aruch Orach Chaim section 489. See all other references quoted in Shlchan Aruch HaRav ibid.

[4] Rabanu Yerucham ben Meshullam (1290-1350), was a prominent rabbi and posek during the period of the Rishonim. He was born in Provence, France. In 1306, after the Jewish expulsion from France, he moved to Toledo, Spain. During this time of his life, he became a student of Rabbi Asher ben Yeciell known as the Rosh. In the year 1330, he began writing his work Sefer Maysharim on civil law. He completed this work in four years. At the end of his life, he wrote his main halachik work Sefer Toldos Adam V'Chava. Various components of halacha as ruled by Rabbenu Yerucham, have been codified in the Shulchan Aruch in the name of Rabbeinu Yerucham. He greatly influenced Rabbi Yosef Karo. He is quoted extensively by Rabbi Karo in both the Shulchan Aruch as well as the Beis Yoseif on the Tur.

[5] Maamar Usfartem Lag Baomer 5711. As far as I know, it is the first and only source to explain the view of Rabanu Yerucham according to Chassidus.

[6] Likkutei Torah Emor, Maamar Usfartem (the first one).

[7] Since the focus is on the expression of emotion in the details of our life, hence there are seven days, representing the seven nuanced ways in which each emotion expresses itself, through love, or through might, or through empathy, or through ambition, etc.

[8] In many ways, this constitutes the basic difference between the Tzaddik and the Banuni in Tanya.

[9] See Tanya Ch. 4, 6, 12, and many more places.

[10] See Tanya ch. 14

[11] For Rambam, both counts even today are biblical. Whereas for Tosefos, both counts today are rabbinic. Perhaps we can connect this with the idea in Sefarim, that the galus for the Ashkenazim was far deeper than for the Sefardim.

- Comment

Class Summary:

In May 2015, John Nash, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, was killed with his wife in a devastating car accident in NJ. It is hard not to shed a tear when you read the biography “A Beautiful Mind” about the tragic and triumphant life of Mr. Nash. Promising to become one of the most promising mathematicians in the world, Nash was struck by the mental illness of schizophrenia. When Nash was offered a prestigious chair at the University of Chicago, he declined because he was planning to become Emperor of Antarctica. John believed that all men who wore red ties were part of a communist conspiracy against him.

His poor wife divorced him, then remarried him, and in 1994 he won the Noble Prize for Economics. But right after the Noble ceremony, there is a scene that represents the profound human triumph of John Nash.

There is something strange about the way we count sefirah—the 49-day count between Passover and Shavuos. The Torah instructs us to count both the days and the weeks. But why is the Torah adamant that we count both the days and the weeks simultaneously? One of these counts is superfluous. What do we gain by counting the week after we have already counted the days? What would be missing if we left out the weeks, or conversely, if we left out the days?

Even more perplexing is the view of the 13th century French and Spanish sage, Rabbeinu Yerucham. He says that it is a biblical mitzvah to count the days also when the Beit HaMikdash is not extant, but the mitzvah to count the weeks applies only when the omer is offered, and is thus today only a rabbinical commandment.

Strange it is. Counting is counting. What exactly is the difference between saying “Today is twenty-eight days of the Omer” and saying “Today is four weeks of the Omer”? How can we make sense of the notion that counting days is a biblical mandate and counting weeks is a rabbinic mandate?

Let’s excavate the mystery of the days and the weeks and the view of Rabanu Yerucham, from the deeper emotional, psychological and spiritual vantage point. This explanation was offered by the Lubavitcher Rebbe during an address, on Lag B’Omer 5711, May 24, 1951.

How did Winston Churchill deal with his depression? How do we define the meaning of Jewish identity? As part of the natural historical process, or as supernatural? Are we part of the natural cycle, embracing its rhythm and changes, or are a chip off another block, governed by a different system, steeped in a reality which is unchangeable? The story of the Nazi desecrating a Torah scroll, which then ended up on the Holy Land.

Dedicated by Shoshana Packouz in loving memory of Kalman Moshe ben Reuven Avigdor

Graciously dedicated by Dan Kramer l'ilui nishmas his beloved mother Ziona Kramer, Tziona bas Gavriel.

Counting Days and Weeks

There are three kinds of people, goes the old joke: those who can count and those who can’t.

There is something strange about the way we count ‘sefirah’—the 49-day count, in the Jewish tradition, between Passover and the festival of Shavuos.

The Talmud states:[1]

Abaye stated, "It is a Mitzvah to count the days, and it is a Mitzvah to count the weeks.” This is because both are mentioned explicitly in the Torah:

Leviticus 23:15-16: From the day following the (first) rest day (of Pesach)—the day you bring the Omer as a wave-offering—you should count for yourselves seven weeks. (When you count them) they should be perfect. You should count until (but not including) fifty days, (i.e.) the day following the seventh week. (On the fiftieth day) you should bring (the first) meal-offering (from the) new (crop) to G-d.

Deuteronomy 16:9-10: You shall count seven weeks for yourself; from [the time] the sickle is first put to the standing crop, you shall begin to count seven weeks. And you shall perform the Festival of Weeks to the Lord, your God, the donation you can afford to give, according to how the Lord, your God, shall bless you.

Clearly, the Torah talks about two forms of counting: counting seven weeks and counting 49 days. We thus fulfill both mandates: At the conclusion of the first week, we count as follows: “Today is seven days, which is one week to the Omer.” The next night, we count as follows: “Today is eight days, which is one week and one day to the Omer.” “Today is forty-eight days, which is six weeks and six days to the Omer.”

Yet this is strange. Why is the Torah adamant that we count both the days and the weeks simultaneously? One of these counts is superfluous. What do we gain by counting the week after counting the days? Either say simply: “Today is seven days to the Omer,” and if you want to know how many weeks that is, you can do the math yourself, or alternatively, stick to weeks: “Today is one week to the Omer,” and you don’t have to be a genius to know how many days that includes!

Biblical or Rabbinic?

There is yet another perplexing matter.

The “Karban Omer” was a barley offering brought to the Holy Temple on the second day of Passover (on the 16th of Nissan). They would harvest barley, grind it to flour, and offer a fistful of the flour on the altar. The rest of the flour would be baked as matzah and eaten by the Kohanim (Omer is the Hebrew name for the volume of flour prepared; it is the volume of 42.2 eggs).

Hence, the Torah states:[2] “And you shall count for yourselves from the morrow of the Sabbath, from the day on which you bring the Omer offering, seven complete weeks shall there be ,until the morrow of the seventh week you shall count fifty days...”

When the Beis HaMikdash (Holy Temple) stood in Jerusalem, this offering of a measure (omer) of barley, brought on the second day of Passover, marked the commencement of the seven-week count. Today, we lack the opportunity to bring the Omer offering on Passover. The question then arises, is there still a mandate to do the sefirat haomer, the counting of the Omer? Without the Omer, are we still obligated to count the seven-week period?

As you may have guessed, there is a dispute among our sages.

שולחן ערוך הרב אורח חיים סימן תפט סעיף ב: ומצוה זו נוהגת בארץ ובחו"ל בפני הבית ושלא בפני הבית. ויש אומרים שבזמן הזה שאין בית המקדש קיים ואין מקריבין העומר אין מצוה זו נוהגת כלל מדברי תורה אלא מדברי סופרים שתיקנו זכר למקדש וכן עיקר.

The Rambam (Maimonides), the Chinuch, the Ravya, and others believe that the mandate to count isn’t dependent on the Omer offering. Even today, we are obligated biblically to count 49 days between Passover and Shavuos.

However, Tosefot and most halachic authorities, including the Code of Jewish Law,[3] maintain the view that the biblical mitzvah of counting directly depends on the actual Omer offering. Hence, today, there is only a rabbinic obligation to count, to commemorate the counting in the time of the Holy Temple. Our counting today is not a full-fledged biblical commandment (mitzvah deoraita) but a rabbinical ordinance that merely commemorates the mitzvah fulfilled in the times of the Beit HaMikdash.

So far so good.

The Third Opinion

But there is a fascinating third and lone opinion, that of the 13th-century French and Spanish sage Rabbeinu Yerucham.[4]

רבינו ירוחם ספר תולדות אדם וחוה, חלק אדם, נתיב ה חלק ד: ונראה לן, משום דכתוב בתורה [שתי פרשיות], שבעה שבועות תספור לך וגו׳ וכתיב נמי מיום הביאכם את עומר וגו׳ שבע שבתות תמימות תהיין, נמצא שלא נכתבה ספירת שבועות כי אם גבי העומר, אבל ספירת הימים [תספרו חמשים יום] לא כתיב גבי עומר, נמצא דספירת הימים הוא מן התורה אפילו בזמן הזה, וספירת השבועות בזמן דאיכא עומר. והיו מברכים זה על זה בזמן שביהמ"ק היה קיים... ובזמן הזה אנו סופרים לשבועות זכר למקדש... לכך אנו אומרים שהם כך וכך שבועות שאין זו ספירה ממש.

He says that it depends which counting we are talking about. The days or the weeks. The counting of the days is a biblical mandate even today, while the counting of the weeks, says Rabbeinu Yerucham, is only a rabbinic mandate.

This third opinion is an interesting combination of the first two: According to Rabbeinu Yerucham, it is a biblical mitzvah to count the days even when the Beit HaMikdash is not extant, but the mitzvah to count the weeks applies only when the Omer is offered and is thus today only a rabbinical commandment.

The rationale behind his view is fascinating. When the Torah states to count the weeks, it is stated in context of the Omer offering; so, without the omer offering, the biblical obligation falls away. But when the Torah states to count the days, it says so independently of the Omer offering. So even without an omer, there is still a mitzvah to count 49 days.

Now this seems really strange. How are we to understand Rabbeinu Yerucham? Counting is counting, what exactly is the difference between saying “Today is twenty-eight days of the Omer” and saying “Today is four weeks of the Omer”? How can we make sense of the notion that counting days is a biblical mandate while counting weeks is a rabbinic mandate?

To be sure, he offers a convincing proof from the Torah text. But that only transfers the question onto the Torah: What would be the logic to command Jews today, in exile, to count only days and not weeks? Yet Jews during the time of the Holy Temple were commanded by the Torah to do both?

The views of Rambam and Tosefos are clear. Either the entire obligation (the count of the days and the weeks) is biblical, or it is all rabbinic. But the split Rabbanu Yerucham suggests seems enigmatic. Why would the Torah make this differentiation? Why would it deny us the opportunity to count weeks during exile, but still obligate us to count days lacking the Holy Temple?

Two Types of Self-Work

Let’s excavate the mystery of the days and the weeks and the three views of Rambam, Tosefos and Rabanu Yerucham, from the deeper emotional, psychological and spiritual vantage point. This explanation was offered by the Lubavitcher Rebbe during an address, on Lag B’Omer 5711, May 24, 1951.[5]

The teachings of Kabbalah and Chassidism describe seven basic character traits in the heart of each human being: Chesed (love, kindness), Gevurah (discipline, boundaries, restraint), Tiferet (beauty, empathy), Netzach (victory, ambition), Hod (humility, gratitude, and acknowledging mistakes), Yesod (bonding and communicatively) and Malchus (leadership, confidence, selflessness).

This is the deeper significance of the “counting of the omer,” the mitzvah to count seven weeks from Passover to Shavuot. Judaism designates a period of the year for “communal therapy,” when together we go through a process of healing our inner selves, step by step, issue by issue, emotion by emotion. For each of the seven weeks, we focus on one of the seven emotions in our lives, examining it, refining it, and fixing it—aligning it with the Divine emotions.[6]

In the first week, we focus on the love in our lives. Do I know how to express and receive love? Do I know how to love? In the second week, we focus on our capacity for creating boundaries. Do I know how to create and maintain proper borders? In the third week, we reflect on our ability to empathize. Do I know how to emphasize? Do I know how to be here for someone else on their terms, not mine? In the fourth week, we look at our capacity to triumph in the face of adversity. Do I know how to win? Do I have ambition? The fifth week is focused on our ability to express gratitude, show vulnerability, and admit mistakes. The sixth week—on our ability to communicate and bond. And finally, in the seventh week, we focus on our skills as leaders. I’m I confident enough to lead? Do I know how to lead? Do I possess inner dignity? Is my leadership driven by insecurity or egotism? I’m I king over myself? Do I possess inner core self-value?

But as we recall, the mitzvah is to count both the days and the weeks. For each of the seven weeks is further divided into seven days. These seven traits are expressed in our life in various thoughts, words and deeds. So during the seven days of each week, we focus each day on another detail of how this particular emotion expresses itself in our lives. If the week-count represents tackling the core of the emotion itself, the day-count represents tackling not the emotion itself, but rather how it expresses itself in our daily lives, in the details of our lives, in our behaviors, words and thoughts.[7]

Transformation vs. Self-Control

When I say, “Today is one week to the omer,” I am saying that today, I managed to tune in to the full scope of that emotion, transforming it and healing it at its core.

Every once in a while, you hear what we call a wonderous journey of incredible healing and transformation. Someone who was struggling with a trauma or an addiction for many years, uncovers a deep awareness, or perhaps goes through a profound healing journey, or a therapeutic program, and they come out completely healed. They have touched such a deep place within themselves, that it completely transformed their life. The trauma is healed; the addiction is gone. Their anger or jealousy is no longer an issue. Like a child who is being toilet trained, at one point, he stops entertaining the idea of using a diaper. He has matured. So too, there is a possibility of counting weeks i.e. completely transforming a particular emotion, completely weeding out the distortions.

The Day Model

But that is a unique experience. And even when it occurs, it may not last forever, or we may still vacillate back to our old coping mechanisms caused by our traumas. We now come to the second model of self-refinement, the “day model.” This is the model that belongs to each of us at every moment. I am not always capable of the week-model, but I am always capable of the day-model. There is no great transformation here, the urges are there, the temptations are there, the dysfunction is there, the addictions are there, the negative emotions are there, and the promiscuous cravings are intact, but I manage to refine the day—meaning I learn how to control where and how that emotion will be expressed in the details of my life. I may not be able to redefine the very core of the emotion—the entire “week”—but I can still choose how it will be channeled, or not channeled, in the details of my life.[8]

Imagine you are driving your car and approaching a red light. Now you've got someone in the backseat screaming, “Go! Run the light! Just do it!” The guy is screaming right in your ear. The screams are loud and annoying, but if you're behind the wheel, no amount of screaming can make you run the light. Why not? Because you can identify the screamer as an alien voice to yourself; he is a stranger bringing up a ludicrous and dangerous idea. You may not be able to stop the screaming, but you can identify it and thus quarantine it, putting it in context of where it belongs—to a strange man hollering stupidity.

But imagine if when hearing that voice “take the red light,” you decide that it is your rational mind speaking to you; you imagine that this is your intelligence speaking to you—then it becomes so much harder to say no.

Same with emotions and thoughts. Even while being emotionally hijacked, I still have the wheel in my hand. I may not have the ability now to transform my urge, and stop the screaming of certain thoughts. Still, as long as I can identify that this thought is not my essence and is coming from a part of me that is insecure and unwholesome, I need not allow that thought to define me and to control my behavior.

Suicidal Thoughts

A woman struggling with suicidal thoughts recently shared with me how she learned to deal with them more effectively.

“I always believed that when I have my suicidal urges, I'm not in control. After all, suicide urges were not something that I could bring up at will - I had to be triggered in a hugely discomforting way for the suicide ideas to surface so vengefully.

“But this time around, I realized that thoughts were just that, thoughts. And it's we who choose if to engage the thoughts and define ourselves by them. We choose to act on our thoughts or not. It's not easy thinking new thoughts when the old familiar thoughts tell you that suicide is the only answer.”

If the only thing people learned was not to be afraid of their experience, that alone would change the world. The moment we can look at our urge or temptation in the eye and say, “Hi! I’m not afraid of you, all you are is a thought,” we have gained control over that urge.

The Text Message

Say you get a text from your wife: “When are you coming home?” Immediately, you experience a thought that produces anger. “Will she ever appreciate how hard I work? What does she think I am doing here in the office? Can’t she just leave me alone!”

But hay, relax. All she asked was when you were coming home, perhaps because she misses you, loves you, and wants to see your face. But due to your own insecurities, you can’t even see that. You are used to your mother bashing you, and you instinctively assume she is also bashing you. But she is not. She just asked a simple, innocent question.

Can I get rid of my insecurity and my anger at the moment? No! But I can IDENTIFY my emotion as coming from my insecure dimensions, and I can say to myself, I will not allow that part of myself to take control over my life. I will not allow the toxic image of myself as the man whom everyone is waiting to criticize to overtake me completely. Once I identify where the emotion comes from, I can quarantine it and let it be what it is, but without allowing it to define me. The key is that I do not get trapped into thinking that that thought is me—that it reflects my essence. No! It is just a thought. It is not me. And it does not have to be me. I define it; it does not define me. It is part of me, but it is not all of me. It is the guy in the back seat screaming, “Take the light.”

I did not manage to refine the week, but I did manage to refine the day—I got control of how my thoughts and emotions manifest themselves in the individual days and behaviors of my life.

Winston Churchill suffered from depression. In his biography, he describes how he came to see his depression as a black dog always accompanying him and sometimes barking very loudly. But the black dog was not him. The depressing thoughts were just that—thoughts.

One of the powerful ideas in Tanya is that thoughts are the “garments of the soul,” not the soul. Garments are made to change. We often see our thoughts as our very selves. But they are not; they are garments. You can change them whenever you want to. [9]

A Beautiful Mind; a Beautiful Life

Several years ago, John Nash, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, was killed with his wife in a devastating car accident in NJ.

It is hard not to shed a tear when you read the biography “A Beautiful Mind” about the tragic and triumphant life of Mr. Nash (later also produced as a film).

John Nash, born in 1928, was named early in his career as one of the most promising mathematicians in the world. Nash is regarded as one of the great mathematicians of the 20th century. He set the foundations of modern game theory— the mathematics of decision-making—while still in his 20s, and his fame grew during his time at Princeton University and at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he met Alicia Larde, a physics major. They married in 1957.

But by the end of the 1950s, insane voices in his head began to overtake his thoughts on mathematical theory. He developed a terrible mental illness. Nash, in his delusions, accused one mathematician of entering his office to steal his ideas and began to hear alien messages. When Nash was offered a prestigious chair at the University of Chicago, he declined because he planned to become Emperor of Antarctica.

John believed that all men who wore red ties were part of a communist conspiracy against him. Nash mailed letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., declaring they were establishing a government. His psychological issues crossed into his professional life when he gave an American Mathematical Society lecture at Columbia University in 1959. While he intended to present proof of the Riemann hypothesis, the lecture was incomprehensible. He spoke as a madman. Colleagues in the audience immediately realized that something was terribly wrong.

He was admitted to the Hospital, where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. For many years he spent periods in psychiatric hospitals, where he received antipsychotic medications and shock therapy.

Due to the stress of dealing with his illness, his wife Alicia divorced him in 1963. And yet Alicia continued to support him throughout his illness. After his final hospital discharge in 1970, he lived in Alicia’s house as a boarder.

It was during this time that he learned how to discard his paranoid delusions consciously. "I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research," Nash later wrote about himself.

He ultimately was allowed by Princeton University to teach again. Over the years, he became a world-renowned mathematician, contributing majorly to the field. In 2001, Alicia decided to marry again her first sweetheart, whom she once divorced. Alicia and John Nash married each other for the second time.

In later years they both became major advocates for mental health care in New Jersey when their son John was also diagnosed with schizophrenia.

In 1994, John Nash won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

What Is Logic?

In the final scene of the film, Nash receives the Nobel Prize. During the ceremony, he says the following:

I've always believed in numbers and the equations and logic that lead to reason.

But after a lifetime of such pursuits, I ask,

"What truly is logic?"

"Who decides reason?"

My quest has taken me through the physical, the metaphysical, the delusional—and back.

And I have made the most important discovery of my career, the most important discovery of my life: It is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logic or reasons can be found.

I'm only here tonight because of you [pointing to his wife, Alicia].

You are the reason I am.

You are all my reasons.

Thank you.

The crowd jumps from their chairs, giving a thundering standing ovation to the brilliant mathematician who has been to hell and back a few times.

And then comes one of the most moving scenes.

Nothing Is Wrong

Right after the Noble Prize ceremony, as John is leaving the hall, the mental disease suddenly attacks him in the most vicious and sinister way. Suddenly, his delusions come right back to him, and in the beautiful hallways of Stockholm, he “sees” the very characters that were responsible for destroying his life. He suddenly “sees” all the communists who he believed were out to destroy him.

It is a potentially tragic moment of epic proportions. Here is a man who just won the Nobel Prize, who has become world-renowned, and who is considered one of the greatest minds of the century. Here is a man standing with his loving wife, basking in the shadow of international glory. And yet, at this very moment, the devil of mental illness strikes lethally, mentally “abducting” poor John Nash.

His wife senses that something is happening; she sees how he has suddenly wandered off. He is not present anymore in the real world. His eyes are elsewhere; his body overtaken by fear.

In deep pain and shock, she turns to her husband and asks him, “What is it? What’s wrong?”

He pauses, looks at the fictional people living in his tormented mind, then looks back at her, and with a smile on his face he says: “Nothing; nothing at all.” He takes her hand and off they go.

It is a moment of profound triumph. Here you have a man at the height of everything, and the schizophrenia suddenly strikes him. There was nothing he could do to get rid of it. It was still there; it never left him. Yet his hard inner world allowed him to identify it as an illness and thus quarantine it. He could define it and place it in context rather than have it define him. He could see it for what it was: an unhealthy mental disease alien to his beautiful essence.

No, he does not get rid of schizophrenia but rather learns how to define it rather than letting it define him. He must be able to at least identify it as thoughts that do not constitute his essence and stem from a part of him that is unhealthy.

John Nash could see all those mental images and say to himself: “These are forces within me; but it is not me. It is a mental illness—and these voices are coming from a part of me that is ill. But I am sitting at the wheel of my life, and I have decided not to allow these thoughts to take over my life. I will continue living, I will continue loving and connecting to my wife and to all the good in my life, even as the devils in my brain never shut up. I can’t count my weeks, but I can count my days.”

Nash once said something very moving about himself. "I wouldn't have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally." He also said, "If I felt completely pressure-less, I don't think I would have gone in this pattern". You see, he managed to even perceive the blessing and the opportunity in his struggle, despite the terrible price he paid for them.

Nash was a hero of real life. Here you have a guy dealing with a terrible mental sickness, but with time, work, and most importantly, with love and support, he learns to stand up to it. He learns how his health isn’t defined by the mental chatter and by what his mind decides to show him now. He has learned that despite all of it, day in and day out, he can show up in his life and be in control, rather than the illness controlling him.

The Accident

On May 23, 2015, John and his wife Alicia were on their way home after a visit to Norway, where Nash had received the Abel Prize for Mathematics from King Harald V for his work.

He did arrange for a limo to pick him and his wife up from Newark airport and take them home to West Windsor, NJ. The plane landed early, so they picked up a regular cab to take them home.

They were both sitting in a cab on the New Jersey Turnpike. When the driver of the taxicab lost control of the vehicle and struck a guardrail. Both John and Alicia were ejected from the car upon impact and died on the spot. Nash was 86 years old; his wife 80.

What Can We Achieve Now?

At last, we can appreciate the depth of the Torah law concerning the counting of the omer. The quest for truth, healing, and perfection continues at all times and under all conditions, even in the darkest hours of exile. Thus, we are instructed to count not only the days but also the weeks. We are charged with the duty of learning self-control (days) and trying to achieve transformation (weeks).[10] But it is here that Rabbeinu Yerucham offers us a deeply comforting thought.

True, in the times of the Holy Temple, a time of great spiritual revelation, the Torah instructs us and empowers us to count both days and weeks. In the presence of such intense spiritual awareness, they also had the ability to count weeks. However today, says Rabbeinu Yerucham, we don’t breathe the same awareness. We are in exile. We live in a spiritually diminished level of awareness. Hence, the biblical obligation is to count the days, to gain control over our behavior. Counting the weeks, i.e. fully transforming our emotions, is only a rabbinic obligation, simply to reminisce and remember that ultimately there is a path of transformation we strive for.[11]

Indeed, as we are living today in the times of redemption, more and more we are experiencing the ability for full healing—transforming our days and our weeks, bidding farewell to our traumas forever.

[1] Menachos 66a

[2] Leviticus 23:15

[3] Tosefos Menachos 66a. Shlchan Aruch Orach Chaim section 489. See all other references quoted in Shlchan Aruch HaRav ibid.

[4] Rabanu Yerucham ben Meshullam (1290-1350), was a prominent rabbi and posek during the period of the Rishonim. He was born in Provence, France. In 1306, after the Jewish expulsion from France, he moved to Toledo, Spain. During this time of his life, he became a student of Rabbi Asher ben Yeciell known as the Rosh. In the year 1330, he began writing his work Sefer Maysharim on civil law. He completed this work in four years. At the end of his life, he wrote his main halachik work Sefer Toldos Adam V'Chava. Various components of halacha as ruled by Rabbenu Yerucham, have been codified in the Shulchan Aruch in the name of Rabbeinu Yerucham. He greatly influenced Rabbi Yosef Karo. He is quoted extensively by Rabbi Karo in both the Shulchan Aruch as well as the Beis Yoseif on the Tur.

[5] Maamar Usfartem Lag Baomer 5711. As far as I know, it is the first and only source to explain the view of Rabanu Yerucham according to Chassidus.

[6] Likkutei Torah Emor, Maamar Usfartem (the first one).

[7] Since the focus is on the expression of emotion in the details of our life, hence there are seven days, representing the seven nuanced ways in which each emotion expresses itself, through love, or through might, or through empathy, or through ambition, etc.

[8] In many ways, this constitutes the basic difference between the Tzaddik and the Banuni in Tanya.

[9] See Tanya Ch. 4, 6, 12, and many more places.

[10] See Tanya ch. 14

[11] For Rambam, both counts even today are biblical. Whereas for Tosefos, both counts today are rabbinic. Perhaps we can connect this with the idea in Sefarim, that the galus for the Ashkenazim was far deeper than for the Sefardim.

Tags

Categories

Essay Sefirah

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 16, 2024

- |

- 8 Iyyar 5784

- |

- 4958 views

It’s a Beautiful Heart

Counting Days and Weeks: Confronting Mental Illness, Trauma, and Depression

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- May 16, 2024

Counting Days and Weeks

There are three kinds of people, goes the old joke: those who can count and those who can’t.

There is something strange about the way we count ‘sefirah’—the 49-day count, in the Jewish tradition, between Passover and the festival of Shavuos.

The Talmud states:[1]

Abaye stated, "It is a Mitzvah to count the days, and it is a Mitzvah to count the weeks.” This is because both are mentioned explicitly in the Torah:

Leviticus 23:15-16: From the day following the (first) rest day (of Pesach)—the day you bring the Omer as a wave-offering—you should count for yourselves seven weeks. (When you count them) they should be perfect. You should count until (but not including) fifty days, (i.e.) the day following the seventh week. (On the fiftieth day) you should bring (the first) meal-offering (from the) new (crop) to G-d.

Deuteronomy 16:9-10: You shall count seven weeks for yourself; from [the time] the sickle is first put to the standing crop, you shall begin to count seven weeks. And you shall perform the Festival of Weeks to the Lord, your God, the donation you can afford to give, according to how the Lord, your God, shall bless you.

Clearly, the Torah talks about two forms of counting: counting seven weeks and counting 49 days. We thus fulfill both mandates: At the conclusion of the first week, we count as follows: “Today is seven days, which is one week to the Omer.” The next night, we count as follows: “Today is eight days, which is one week and one day to the Omer.” “Today is forty-eight days, which is six weeks and six days to the Omer.”

Yet this is strange. Why is the Torah adamant that we count both the days and the weeks simultaneously? One of these counts is superfluous. What do we gain by counting the week after counting the days? Either say simply: “Today is seven days to the Omer,” and if you want to know how many weeks that is, you can do the math yourself, or alternatively, stick to weeks: “Today is one week to the Omer,” and you don’t have to be a genius to know how many days that includes!

Biblical or Rabbinic?

There is yet another perplexing matter.

The “Karban Omer” was a barley offering brought to the Holy Temple on the second day of Passover (on the 16th of Nissan). They would harvest barley, grind it to flour, and offer a fistful of the flour on the altar. The rest of the flour would be baked as matzah and eaten by the Kohanim (Omer is the Hebrew name for the volume of flour prepared; it is the volume of 42.2 eggs).

Hence, the Torah states:[2] “And you shall count for yourselves from the morrow of the Sabbath, from the day on which you bring the Omer offering, seven complete weeks shall there be ,until the morrow of the seventh week you shall count fifty days...”

When the Beis HaMikdash (Holy Temple) stood in Jerusalem, this offering of a measure (omer) of barley, brought on the second day of Passover, marked the commencement of the seven-week count. Today, we lack the opportunity to bring the Omer offering on Passover. The question then arises, is there still a mandate to do the sefirat haomer, the counting of the Omer? Without the Omer, are we still obligated to count the seven-week period?

As you may have guessed, there is a dispute among our sages.

שולחן ערוך הרב אורח חיים סימן תפט סעיף ב: ומצוה זו נוהגת בארץ ובחו"ל בפני הבית ושלא בפני הבית. ויש אומרים שבזמן הזה שאין בית המקדש קיים ואין מקריבין העומר אין מצוה זו נוהגת כלל מדברי תורה אלא מדברי סופרים שתיקנו זכר למקדש וכן עיקר.

The Rambam (Maimonides), the Chinuch, the Ravya, and others believe that the mandate to count isn’t dependent on the Omer offering. Even today, we are obligated biblically to count 49 days between Passover and Shavuos.

However, Tosefot and most halachic authorities, including the Code of Jewish Law,[3] maintain the view that the biblical mitzvah of counting directly depends on the actual Omer offering. Hence, today, there is only a rabbinic obligation to count, to commemorate the counting in the time of the Holy Temple. Our counting today is not a full-fledged biblical commandment (mitzvah deoraita) but a rabbinical ordinance that merely commemorates the mitzvah fulfilled in the times of the Beit HaMikdash.

So far so good.

The Third Opinion

But there is a fascinating third and lone opinion, that of the 13th-century French and Spanish sage Rabbeinu Yerucham.[4]

רבינו ירוחם ספר תולדות אדם וחוה, חלק אדם, נתיב ה חלק ד: ונראה לן, משום דכתוב בתורה [שתי פרשיות], שבעה שבועות תספור לך וגו׳ וכתיב נמי מיום הביאכם את עומר וגו׳ שבע שבתות תמימות תהיין, נמצא שלא נכתבה ספירת שבועות כי אם גבי העומר, אבל ספירת הימים [תספרו חמשים יום] לא כתיב גבי עומר, נמצא דספירת הימים הוא מן התורה אפילו בזמן הזה, וספירת השבועות בזמן דאיכא עומר. והיו מברכים זה על זה בזמן שביהמ"ק היה קיים... ובזמן הזה אנו סופרים לשבועות זכר למקדש... לכך אנו אומרים שהם כך וכך שבועות שאין זו ספירה ממש.

He says that it depends which counting we are talking about. The days or the weeks. The counting of the days is a biblical mandate even today, while the counting of the weeks, says Rabbeinu Yerucham, is only a rabbinic mandate.

This third opinion is an interesting combination of the first two: According to Rabbeinu Yerucham, it is a biblical mitzvah to count the days even when the Beit HaMikdash is not extant, but the mitzvah to count the weeks applies only when the Omer is offered and is thus today only a rabbinical commandment.

The rationale behind his view is fascinating. When the Torah states to count the weeks, it is stated in context of the Omer offering; so, without the omer offering, the biblical obligation falls away. But when the Torah states to count the days, it says so independently of the Omer offering. So even without an omer, there is still a mitzvah to count 49 days.

Now this seems really strange. How are we to understand Rabbeinu Yerucham? Counting is counting, what exactly is the difference between saying “Today is twenty-eight days of the Omer” and saying “Today is four weeks of the Omer”? How can we make sense of the notion that counting days is a biblical mandate while counting weeks is a rabbinic mandate?

To be sure, he offers a convincing proof from the Torah text. But that only transfers the question onto the Torah: What would be the logic to command Jews today, in exile, to count only days and not weeks? Yet Jews during the time of the Holy Temple were commanded by the Torah to do both?

The views of Rambam and Tosefos are clear. Either the entire obligation (the count of the days and the weeks) is biblical, or it is all rabbinic. But the split Rabbanu Yerucham suggests seems enigmatic. Why would the Torah make this differentiation? Why would it deny us the opportunity to count weeks during exile, but still obligate us to count days lacking the Holy Temple?

Two Types of Self-Work

Let’s excavate the mystery of the days and the weeks and the three views of Rambam, Tosefos and Rabanu Yerucham, from the deeper emotional, psychological and spiritual vantage point. This explanation was offered by the Lubavitcher Rebbe during an address, on Lag B’Omer 5711, May 24, 1951.[5]

The teachings of Kabbalah and Chassidism describe seven basic character traits in the heart of each human being: Chesed (love, kindness), Gevurah (discipline, boundaries, restraint), Tiferet (beauty, empathy), Netzach (victory, ambition), Hod (humility, gratitude, and acknowledging mistakes), Yesod (bonding and communicatively) and Malchus (leadership, confidence, selflessness).

This is the deeper significance of the “counting of the omer,” the mitzvah to count seven weeks from Passover to Shavuot. Judaism designates a period of the year for “communal therapy,” when together we go through a process of healing our inner selves, step by step, issue by issue, emotion by emotion. For each of the seven weeks, we focus on one of the seven emotions in our lives, examining it, refining it, and fixing it—aligning it with the Divine emotions.[6]

In the first week, we focus on the love in our lives. Do I know how to express and receive love? Do I know how to love? In the second week, we focus on our capacity for creating boundaries. Do I know how to create and maintain proper borders? In the third week, we reflect on our ability to empathize. Do I know how to emphasize? Do I know how to be here for someone else on their terms, not mine? In the fourth week, we look at our capacity to triumph in the face of adversity. Do I know how to win? Do I have ambition? The fifth week is focused on our ability to express gratitude, show vulnerability, and admit mistakes. The sixth week—on our ability to communicate and bond. And finally, in the seventh week, we focus on our skills as leaders. I’m I confident enough to lead? Do I know how to lead? Do I possess inner dignity? Is my leadership driven by insecurity or egotism? I’m I king over myself? Do I possess inner core self-value?

But as we recall, the mitzvah is to count both the days and the weeks. For each of the seven weeks is further divided into seven days. These seven traits are expressed in our life in various thoughts, words and deeds. So during the seven days of each week, we focus each day on another detail of how this particular emotion expresses itself in our lives. If the week-count represents tackling the core of the emotion itself, the day-count represents tackling not the emotion itself, but rather how it expresses itself in our daily lives, in the details of our lives, in our behaviors, words and thoughts.[7]

Transformation vs. Self-Control

When I say, “Today is one week to the omer,” I am saying that today, I managed to tune in to the full scope of that emotion, transforming it and healing it at its core.

Every once in a while, you hear what we call a wonderous journey of incredible healing and transformation. Someone who was struggling with a trauma or an addiction for many years, uncovers a deep awareness, or perhaps goes through a profound healing journey, or a therapeutic program, and they come out completely healed. They have touched such a deep place within themselves, that it completely transformed their life. The trauma is healed; the addiction is gone. Their anger or jealousy is no longer an issue. Like a child who is being toilet trained, at one point, he stops entertaining the idea of using a diaper. He has matured. So too, there is a possibility of counting weeks i.e. completely transforming a particular emotion, completely weeding out the distortions.

The Day Model

But that is a unique experience. And even when it occurs, it may not last forever, or we may still vacillate back to our old coping mechanisms caused by our traumas. We now come to the second model of self-refinement, the “day model.” This is the model that belongs to each of us at every moment. I am not always capable of the week-model, but I am always capable of the day-model. There is no great transformation here, the urges are there, the temptations are there, the dysfunction is there, the addictions are there, the negative emotions are there, and the promiscuous cravings are intact, but I manage to refine the day—meaning I learn how to control where and how that emotion will be expressed in the details of my life. I may not be able to redefine the very core of the emotion—the entire “week”—but I can still choose how it will be channeled, or not channeled, in the details of my life.[8]

Imagine you are driving your car and approaching a red light. Now you've got someone in the backseat screaming, “Go! Run the light! Just do it!” The guy is screaming right in your ear. The screams are loud and annoying, but if you're behind the wheel, no amount of screaming can make you run the light. Why not? Because you can identify the screamer as an alien voice to yourself; he is a stranger bringing up a ludicrous and dangerous idea. You may not be able to stop the screaming, but you can identify it and thus quarantine it, putting it in context of where it belongs—to a strange man hollering stupidity.

But imagine if when hearing that voice “take the red light,” you decide that it is your rational mind speaking to you; you imagine that this is your intelligence speaking to you—then it becomes so much harder to say no.

Same with emotions and thoughts. Even while being emotionally hijacked, I still have the wheel in my hand. I may not have the ability now to transform my urge, and stop the screaming of certain thoughts. Still, as long as I can identify that this thought is not my essence and is coming from a part of me that is insecure and unwholesome, I need not allow that thought to define me and to control my behavior.

Suicidal Thoughts

A woman struggling with suicidal thoughts recently shared with me how she learned to deal with them more effectively.

“I always believed that when I have my suicidal urges, I'm not in control. After all, suicide urges were not something that I could bring up at will - I had to be triggered in a hugely discomforting way for the suicide ideas to surface so vengefully.

“But this time around, I realized that thoughts were just that, thoughts. And it's we who choose if to engage the thoughts and define ourselves by them. We choose to act on our thoughts or not. It's not easy thinking new thoughts when the old familiar thoughts tell you that suicide is the only answer.”

If the only thing people learned was not to be afraid of their experience, that alone would change the world. The moment we can look at our urge or temptation in the eye and say, “Hi! I’m not afraid of you, all you are is a thought,” we have gained control over that urge.

The Text Message

Say you get a text from your wife: “When are you coming home?” Immediately, you experience a thought that produces anger. “Will she ever appreciate how hard I work? What does she think I am doing here in the office? Can’t she just leave me alone!”

But hay, relax. All she asked was when you were coming home, perhaps because she misses you, loves you, and wants to see your face. But due to your own insecurities, you can’t even see that. You are used to your mother bashing you, and you instinctively assume she is also bashing you. But she is not. She just asked a simple, innocent question.

Can I get rid of my insecurity and my anger at the moment? No! But I can IDENTIFY my emotion as coming from my insecure dimensions, and I can say to myself, I will not allow that part of myself to take control over my life. I will not allow the toxic image of myself as the man whom everyone is waiting to criticize to overtake me completely. Once I identify where the emotion comes from, I can quarantine it and let it be what it is, but without allowing it to define me. The key is that I do not get trapped into thinking that that thought is me—that it reflects my essence. No! It is just a thought. It is not me. And it does not have to be me. I define it; it does not define me. It is part of me, but it is not all of me. It is the guy in the back seat screaming, “Take the light.”

I did not manage to refine the week, but I did manage to refine the day—I got control of how my thoughts and emotions manifest themselves in the individual days and behaviors of my life.

Winston Churchill suffered from depression. In his biography, he describes how he came to see his depression as a black dog always accompanying him and sometimes barking very loudly. But the black dog was not him. The depressing thoughts were just that—thoughts.

One of the powerful ideas in Tanya is that thoughts are the “garments of the soul,” not the soul. Garments are made to change. We often see our thoughts as our very selves. But they are not; they are garments. You can change them whenever you want to. [9]

A Beautiful Mind; a Beautiful Life

Several years ago, John Nash, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, was killed with his wife in a devastating car accident in NJ.

It is hard not to shed a tear when you read the biography “A Beautiful Mind” about the tragic and triumphant life of Mr. Nash (later also produced as a film).

John Nash, born in 1928, was named early in his career as one of the most promising mathematicians in the world. Nash is regarded as one of the great mathematicians of the 20th century. He set the foundations of modern game theory— the mathematics of decision-making—while still in his 20s, and his fame grew during his time at Princeton University and at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he met Alicia Larde, a physics major. They married in 1957.

But by the end of the 1950s, insane voices in his head began to overtake his thoughts on mathematical theory. He developed a terrible mental illness. Nash, in his delusions, accused one mathematician of entering his office to steal his ideas and began to hear alien messages. When Nash was offered a prestigious chair at the University of Chicago, he declined because he planned to become Emperor of Antarctica.

John believed that all men who wore red ties were part of a communist conspiracy against him. Nash mailed letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., declaring they were establishing a government. His psychological issues crossed into his professional life when he gave an American Mathematical Society lecture at Columbia University in 1959. While he intended to present proof of the Riemann hypothesis, the lecture was incomprehensible. He spoke as a madman. Colleagues in the audience immediately realized that something was terribly wrong.

He was admitted to the Hospital, where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. For many years he spent periods in psychiatric hospitals, where he received antipsychotic medications and shock therapy.

Due to the stress of dealing with his illness, his wife Alicia divorced him in 1963. And yet Alicia continued to support him throughout his illness. After his final hospital discharge in 1970, he lived in Alicia’s house as a boarder.

It was during this time that he learned how to discard his paranoid delusions consciously. "I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research," Nash later wrote about himself.

He ultimately was allowed by Princeton University to teach again. Over the years, he became a world-renowned mathematician, contributing majorly to the field. In 2001, Alicia decided to marry again her first sweetheart, whom she once divorced. Alicia and John Nash married each other for the second time.

In later years they both became major advocates for mental health care in New Jersey when their son John was also diagnosed with schizophrenia.

In 1994, John Nash won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

What Is Logic?

In the final scene of the film, Nash receives the Nobel Prize. During the ceremony, he says the following:

I've always believed in numbers and the equations and logic that lead to reason.

But after a lifetime of such pursuits, I ask,

"What truly is logic?"

"Who decides reason?"

My quest has taken me through the physical, the metaphysical, the delusional—and back.

And I have made the most important discovery of my career, the most important discovery of my life: It is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logic or reasons can be found.

I'm only here tonight because of you [pointing to his wife, Alicia].

You are the reason I am.

You are all my reasons.

Thank you.

The crowd jumps from their chairs, giving a thundering standing ovation to the brilliant mathematician who has been to hell and back a few times.

And then comes one of the most moving scenes.

Nothing Is Wrong

Right after the Noble Prize ceremony, as John is leaving the hall, the mental disease suddenly attacks him in the most vicious and sinister way. Suddenly, his delusions come right back to him, and in the beautiful hallways of Stockholm, he “sees” the very characters that were responsible for destroying his life. He suddenly “sees” all the communists who he believed were out to destroy him.

It is a potentially tragic moment of epic proportions. Here is a man who just won the Nobel Prize, who has become world-renowned, and who is considered one of the greatest minds of the century. Here is a man standing with his loving wife, basking in the shadow of international glory. And yet, at this very moment, the devil of mental illness strikes lethally, mentally “abducting” poor John Nash.

His wife senses that something is happening; she sees how he has suddenly wandered off. He is not present anymore in the real world. His eyes are elsewhere; his body overtaken by fear.

In deep pain and shock, she turns to her husband and asks him, “What is it? What’s wrong?”

He pauses, looks at the fictional people living in his tormented mind, then looks back at her, and with a smile on his face he says: “Nothing; nothing at all.” He takes her hand and off they go.