Elkana Vizel's Last Letter

Jewish History Is a Study of the Future: “Moses and the Children of Israel Will Sing”

- January 25, 2024

- |

- 15 Sh'vat 5784

Rabbi YY Jacobson

7015 views

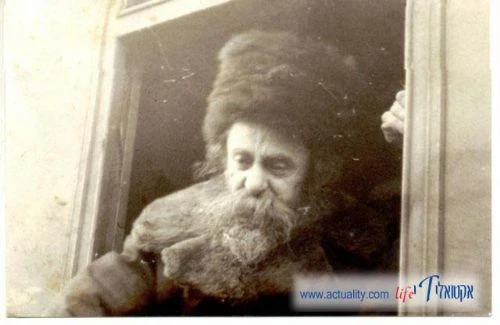

The Belzer Rebbe, Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880-1957)

Elkana Vizel's Last Letter

Jewish History Is a Study of the Future: “Moses and the Children of Israel Will Sing”

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 25, 2024

Elkanah Vizel

Before heading into battle, Master Sgt. Elkana Vizel, 35, penned a letter for his loved ones. At his funeral this week, his widow read the letter.

The father of four young children, Rabbi Elkana Vizel was among 21 reservists killed last Monday night in Northern Gaza.

Despite sustaining injuries in Operation Protective Edge and having the choice to stay out of combat service, Elkana opted to enlist in the reserves, dedicating himself to defending his people. In his heartfelt letter to his loved ones, he expressed unwavering conviction in his decision to return to the frontlines. Here is what he wrote:

If you are reading these words, something must have happened to me. If I was kidnapped, I demand that no deal be made for the release of any terrorist to release me. Our overwhelming victory is more important than anything, so please continue to work with all your might so that the victory is as overwhelming as possible.

Maybe I fell in battle. When a soldier falls in battle, it is sad, but I ask you to be happy. Don't be sad when you part with me. Touch hearts, hold each other's hands, and strengthen each other. We have so much to be proud and happy about.

We are writing the most significant moments in the history of our nation and the entire world. So please, be happy, be optimistic, keep choosing life all the time. Spread love, light, and optimism. Look at your loved ones in the whites of their eyes and remind them that everything we go through in this life is worth it and we have something to live for.

Don't stop the power of life for a moment. I was already wounded in Operation Tzuk Eitan, but I do not regret that I returned to fight. This is the best decision I ever made.

We have no words to describe the nobility, love, purity and holiness of our soldiers and our brothers and sisters fighting for their life. Elkana's letter brought back a story and message that transpired 80 years ago, in one of the darkest moments of our history.

Future Tense

"That day, G-d saved Israel from the hands of the Egyptians . . . The Israelites saw the great power G-d had displayed against the Egyptians, and the people were in awe of G-d. They believed in G-d and in his servant Moses. Moses and the Israelites then sang this song, saying…"[1]

The Song at the Sea was one of the great epiphanies of history. The sages said that even the humblest of Jews saw at that moment what even the greatest of prophets was not privileged to see. For the first time, they broke into a collective song—a song we recite every day during the morning prayers.

Yet, as is often the case, the English translation does not capture all of the nuances. In the original text, the Torah states:

Then Moses and the children of Israel will sing this song to the Lord, and they spoke, saying, I will sing to the Lord, for very exalted is He; a horse and its rider He cast into the sea.

בשלח טו, א: אָ֣ז יָשִֽׁיר־משֶׁה֩ וּבְנֵ֨י יִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ לַֽיהֹוָ֔ה וַיֹּֽאמְר֖וּ לֵאמֹ֑ר אָשִׁ֤ירָה לַּֽיהֹוָה֙ כִּֽי־גָאֹ֣ה גָּאָ֔ה ס֥וּס וְרֹֽכְב֖וֹ רָמָ֥ה בַיָּֽם:

It speaks of Moses’ and the Jews’ singing, in the future tense. This is profoundly strange. The Torah is relating a story that occurred in the past, not one that will occur in the future. It seems like a “bad grammatical error.”

The sages, quoted by Rashi, offer a fascinating insight:

סנהדרין צא, ב: תניא אמר רבי מאיר מניין לתחיית המתים מן התורה שנאמר (שמות טו, א) אז ישיר משה ובני ישראל את השירה הזאת לה', שר לא נאמר אלא ישיר מכאן לתחיית המתים מן התורה.

One of the principles of the Jewish faith is the belief in Techiyas Hamesim, the resurrection of the dead, following the messianic era. Death is not the end of the story. The soul continues to live and exist, spiritually. What is more, the soul will return back to a body.

This is why the Torah chooses to describe the song in the future tense: Moses and his people will indeed sing in the future, after the resurrection. Their song was not only a story of the past; it will also occur in the future.

While this is a fascinating idea, it still begs the question: Why does the Torah specifically hint to the future resurrection here, as opposed to any other place in the Torah? And why will Moses and Israel sing in the future as well?

After the War

The following story happened on this very Shabbos, 80 years ago.[2]

One of the great rabbis of Pre-war Europe was Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880 – 1957), the fourth Rebbe of the Belz Chasidic dynasty (Belz is a city in Galicia, Poland.) He led the movement from 1926 until his death in 1957.

Known for his piety and saintliness, Reb Aharon of Belz was called the "Wonder Rabbi" by Jews and gentiles alike for the miracles he performed. He barely ate or slept. He was made of “spiritual stuff.” (The Lubavitcher Rebbe once visited him in Berlin, and described him as “tzurah bli chomer,” energy without matter.)

His reign as Rebbe saw the devastation of the Belz community, along with most of European Jewry during the Holocaust. During the war, Reb Aharon was high on the list of Gestapo targets as a high-profile Rebbe. They murdered his wife and each of his children and grandchildren. He had no one left. With the support and financial assistance of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe in the US, and Belzer Chasidim in Israel, England, and the United States, he and his half-brother, Rabbi Mordechai of Bilgoray, managed to escape from Poland into Hungary, then into Turkey, Lebanon, and finally into Israel, in February 1944. He remarried but had no children.

Most thought that Belz was an item of history. Yet, the impossible occurred. His half-brother Rabbi Mordechai also remarried and had a son, then died suddenly a few months later. Reb Aharon raised his half-brother's year-old son, Yissachar Dov, and groomed him to succeed him as Belzer Rebbe. Today, it is one of the largest Chassidic groups in Israel, numbering more than 50,000, with hundreds of institutions, schools, synagogues, and yeshivos.

The Belzer Rebbe not once said any of the prescribed prayers like Yizkor or Kaddish for his wife and children, because he felt that those who had been slain by the Nazis for being Jews were of transcendent holiness; their spiritual stature was beyond our comprehension. Any words about them that we might utter were irrelevant and perhaps even a desecration of their memory.

For Reb Aharon, the only proper way to respond to the near-destruction of Belz and honor the memory of the dead was to build new institutions and slowly nurture a new generation of Chasidim. This is what he did for the remainder of his life. He settled in secular Zionist Tel Aviv, and not in the more religious Jerusalem because, he said, it is the only city without a Church or Mosque.

The First Shabbos

The first Shabbos after he arrived in Israel during the winter of 1944 was Shabbos Parshas Beshalach, and he spent it in Haifa. He was alone in the world, without a single relative (save his brother) alive.

During the Shabbos, he held a “tisch,” a formal Chassidic gathering, in which Chassidim sing, dance, and share words of inspiration and Torah. The Belzer Rebbe quickly realized that the Holocaust survivors present, who had endured indescribable suffering and had lost virtually everything they had, were in no mood of singing. The Rebbe decided to address himself and his few broken Chassidim who had survived.

The Belzer Rebbe raised the above question of why the Torah specifically alludes to techiyas hameisim, the resurrection of the dead, in conjunction with the song that was sung celebrating the splitting of the Red Sea?

He gave this chilling answer. When the Jewish people sang the Song of the Sea, much of the nation was not present. How many people did not survive the enslavement of Egypt? How many Jewish children were drowned in the Nile? How many Jews never lived to see the day of the Exodus? How many refused to embark on a journey into the unknown?

According to tradition, only a fifth of the Jewish people made it out.[3] 80% of the Jews died in Egypt. It is safe to say that everyone who did make it out of Egypt had lost relatives and could not fully rejoice in the miracles they were witnessing. Now, the sea split. The wonder of wonders. Moses says to them, “It is time to sing." But they responded, "Sing? How can we sing? Eighty percent of our people are missing!"

Hence, the Torah says, “Moses and the children of Israel will sing,” in the future tense. Moses explained to his people, that the story is far from over. The Jews in Egypt have died, but their souls are alive, and they will return during the resurrection of the dead. We can sing now, said Moses, not because there is no pain, but because despite the pain, we do not believe we have seen the end of the story. We can celebrate the future.

Future and Past

This is what sets apart Jewish history. All of history is, by definition, a study of the past. Jewish history alone is unique. It is a story of the past based on the future. For the Jewish people, history is defined not only by the past but also by the future. Since we know that redemption will come, we go back and redefine exile as the catalyst for redemption and healing.

For the Jewish people, the future defines and gives meaning to the past.

With this, the Belzer Rebbe inspired his students to begin singing yet again as they arrived at the soil of the Holy Land, on Shabbos Beshalach 1944, 80 years ago.

His disciples did sing. And if you visit the main Belz synagogue in Jerusalem, you can hear thousands of Jews, young and old, singing and celebrating Jewish life.

Sunrise

I once read an article by a survivor of Auschwitz. He related how every morning, as the sun rose over Auschwitz, his heart would swell with anger. How dare you?! How can the sun be so indifferent to the suffering of millions and just rise again to cast its warm glow on a world drenched in the blood of the purest and holiest? How can the sun be so cruel and apathetic? Where was the protest?

But, he continued his story, he survived. I came out of the hell. And the day after liberation, as I lay in a bed for the first time in years, I watched the sunrise. For the first time, I felt so grateful for the sun. I felt empowered that after the long night, which seemed to never end, light has at last arrived.

This is the story of our people. Our sun has set. But our sun will also rise. Life, love, and hope will prevail. “Netzach Yisroel Lo Yishaker,” the Eternal One of Israel does not lie. There will be an end to the night. “Moses and the children of Israel will sing.”

And the singing can begin now. We will see Moshiach very very soon -- may it be NOW!

__________________

[1] Exodus 14:15.

[2] The story is recorded in the book “B’kdushaso Shel Aaron,” page 436.

[3] Mechilta and Rashi Exodus 13:2- Comment

Class Summary:

As is often the case, the English translation does not capture all of the nuances of the original text. The Torah states: “Then Moses and the children of Israel will sing this song to the Lord…” This is strange. The Torah is relating a story that occurred in the past, not one that will occur in the future. It seems like a grammatical error.

The sages, quoted by Rashi, offer a fascinating insight: One of the principles of Jewish faith is the belief in Techiyas Hamesim, the resurrection of the dead, following the messianic era. It is the notion that death is not the end of the story. This is why the Torah chooses to describe the song in the future tense: Moses and his people will indeed sing in the future, after the resurrection. Their song was not only a story of the past; it will also occur in the future.

While this is a fascinating idea, it still begs the question: Why does the Torah specifically hint to the future resurrection here as opposed to any other place in the Torah?

I wish to share with you a story that happened on this very Shabbos, more than seven decades ago. One of the great rabbis of Pre-war Europe was Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880–1957), the fourth Rebbe of the Belz Chasidic dynasty. He led the movement from 1926 until his death in 1957. Known for his piety and mysticism, Reb Aharon was called the "Wonder Rabbi" by Jews and gentiles alike for the miracles he performed. He barely ate or slept. He was made of “spiritual stuff.”

He lost his entire family and most of his followers in the war. When he escaped and made it to Israel in February 1944, he spent his first Shabbos, Parshat Beshalach, in Haifa. After the horrible pain they endured, nobody was in the mood of singing. And the Belzer Rebbe shared an incredible insight into the nature of Jewish history. “Moshe will sing.”

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein in honor of Sholom Yosef Gavriel ben Maya Tifcha, Gavriel Nash.

Dedicated by Yisroel Yitzchak HaKohain Kaplan in honor of Yud Shevat and the 74th yartzeit of the Previous Rebbe and in honor of our brave soldiers.

Dedicated by Charline Rubinstein In memory of her father, Rabbi Yaakov ben Moshe Masoud Nezri z"l, grandson of Rabbi Yitzhak Abihsera, and her brother, Abba ben Moshe Masoud Nezri z"l

Elkanah Vizel

Before heading into battle, Master Sgt. Elkana Vizel, 35, penned a letter for his loved ones. At his funeral this week, his widow read the letter.

The father of four young children, Rabbi Elkana Vizel was among 21 reservists killed last Monday night in Northern Gaza.

Despite sustaining injuries in Operation Protective Edge and having the choice to stay out of combat service, Elkana opted to enlist in the reserves, dedicating himself to defending his people. In his heartfelt letter to his loved ones, he expressed unwavering conviction in his decision to return to the frontlines. Here is what he wrote:

If you are reading these words, something must have happened to me. If I was kidnapped, I demand that no deal be made for the release of any terrorist to release me. Our overwhelming victory is more important than anything, so please continue to work with all your might so that the victory is as overwhelming as possible.

Maybe I fell in battle. When a soldier falls in battle, it is sad, but I ask you to be happy. Don't be sad when you part with me. Touch hearts, hold each other's hands, and strengthen each other. We have so much to be proud and happy about.

We are writing the most significant moments in the history of our nation and the entire world. So please, be happy, be optimistic, keep choosing life all the time. Spread love, light, and optimism. Look at your loved ones in the whites of their eyes and remind them that everything we go through in this life is worth it and we have something to live for.

Don't stop the power of life for a moment. I was already wounded in Operation Tzuk Eitan, but I do not regret that I returned to fight. This is the best decision I ever made.

We have no words to describe the nobility, love, purity and holiness of our soldiers and our brothers and sisters fighting for their life. Elkana's letter brought back a story and message that transpired 80 years ago, in one of the darkest moments of our history.

Future Tense

"That day, G-d saved Israel from the hands of the Egyptians . . . The Israelites saw the great power G-d had displayed against the Egyptians, and the people were in awe of G-d. They believed in G-d and in his servant Moses. Moses and the Israelites then sang this song, saying…"[1]

The Song at the Sea was one of the great epiphanies of history. The sages said that even the humblest of Jews saw at that moment what even the greatest of prophets was not privileged to see. For the first time, they broke into a collective song—a song we recite every day during the morning prayers.

Yet, as is often the case, the English translation does not capture all of the nuances. In the original text, the Torah states:

|

Then Moses and the children of Israel will sing this song to the Lord, and they spoke, saying, I will sing to the Lord, for very exalted is He; a horse and its rider He cast into the sea. |

|

בשלח טו, א: אָ֣ז יָשִֽׁיר־משֶׁה֩ וּבְנֵ֨י יִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ לַֽיהֹוָ֔ה וַיֹּֽאמְר֖וּ לֵאמֹ֑ר אָשִׁ֤ירָה לַּֽיהֹוָה֙ כִּֽי־גָאֹ֣ה גָּאָ֔ה ס֥וּס וְרֹֽכְב֖וֹ רָמָ֥ה בַיָּֽם: |

It speaks of Moses’ and the Jews’ singing, in the future tense. This is profoundly strange. The Torah is relating a story that occurred in the past, not one that will occur in the future. It seems like a “bad grammatical error.”

The sages, quoted by Rashi, offer a fascinating insight:

סנהדרין צא, ב: תניא אמר רבי מאיר מניין לתחיית המתים מן התורה שנאמר (שמות טו, א) אז ישיר משה ובני ישראל את השירה הזאת לה', שר לא נאמר אלא ישיר מכאן לתחיית המתים מן התורה.

One of the principles of the Jewish faith is the belief in Techiyas Hamesim, the resurrection of the dead, following the messianic era. Death is not the end of the story. The soul continues to live and exist, spiritually. What is more, the soul will return back to a body.

This is why the Torah chooses to describe the song in the future tense: Moses and his people will indeed sing in the future, after the resurrection. Their song was not only a story of the past; it will also occur in the future.

While this is a fascinating idea, it still begs the question: Why does the Torah specifically hint to the future resurrection here, as opposed to any other place in the Torah? And why will Moses and Israel sing in the future as well?

After the War

The following story happened on this very Shabbos, 80 years ago.[2]

One of the great rabbis of Pre-war Europe was Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880 – 1957), the fourth Rebbe of the Belz Chasidic dynasty (Belz is a city in Galicia, Poland.) He led the movement from 1926 until his death in 1957.

Known for his piety and saintliness, Reb Aharon of Belz was called the "Wonder Rabbi" by Jews and gentiles alike for the miracles he performed. He barely ate or slept. He was made of “spiritual stuff.” (The Lubavitcher Rebbe once visited him in Berlin, and described him as “tzurah bli chomer,” energy without matter.)

His reign as Rebbe saw the devastation of the Belz community, along with most of European Jewry during the Holocaust. During the war, Reb Aharon was high on the list of Gestapo targets as a high-profile Rebbe. They murdered his wife and each of his children and grandchildren. He had no one left. With the support and financial assistance of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe in the US, and Belzer Chasidim in Israel, England, and the United States, he and his half-brother, Rabbi Mordechai of Bilgoray, managed to escape from Poland into Hungary, then into Turkey, Lebanon, and finally into Israel, in February 1944. He remarried but had no children.

Most thought that Belz was an item of history. Yet, the impossible occurred. His half-brother Rabbi Mordechai also remarried and had a son, then died suddenly a few months later. Reb Aharon raised his half-brother's year-old son, Yissachar Dov, and groomed him to succeed him as Belzer Rebbe. Today, it is one of the largest Chassidic groups in Israel, numbering more than 50,000, with hundreds of institutions, schools, synagogues, and yeshivos.

The Belzer Rebbe not once said any of the prescribed prayers like Yizkor or Kaddish for his wife and children, because he felt that those who had been slain by the Nazis for being Jews were of transcendent holiness; their spiritual stature was beyond our comprehension. Any words about them that we might utter were irrelevant and perhaps even a desecration of their memory.

For Reb Aharon, the only proper way to respond to the near-destruction of Belz and honor the memory of the dead was to build new institutions and slowly nurture a new generation of Chasidim. This is what he did for the remainder of his life. He settled in secular Zionist Tel Aviv, and not in the more religious Jerusalem because, he said, it is the only city without a Church or Mosque.

The First Shabbos

The first Shabbos after he arrived in Israel during the winter of 1944 was Shabbos Parshas Beshalach, and he spent it in Haifa. He was alone in the world, without a single relative (save his brother) alive.

During the Shabbos, he held a “tisch,” a formal Chassidic gathering, in which Chassidim sing, dance, and share words of inspiration and Torah. The Belzer Rebbe quickly realized that the Holocaust survivors present, who had endured indescribable suffering and had lost virtually everything they had, were in no mood of singing. The Rebbe decided to address himself and his few broken Chassidim who had survived.

The Belzer Rebbe raised the above question of why the Torah specifically alludes to techiyas hameisim, the resurrection of the dead, in conjunction with the song that was sung celebrating the splitting of the Red Sea?

He gave this chilling answer. When the Jewish people sang the Song of the Sea, much of the nation was not present. How many people did not survive the enslavement of Egypt? How many Jewish children were drowned in the Nile? How many Jews never lived to see the day of the Exodus? How many refused to embark on a journey into the unknown?

According to tradition, only a fifth of the Jewish people made it out.[3] 80% of the Jews died in Egypt. It is safe to say that everyone who did make it out of Egypt had lost relatives and could not fully rejoice in the miracles they were witnessing. Now, the sea split. The wonder of wonders. Moses says to them, “It is time to sing." But they responded, "Sing? How can we sing? Eighty percent of our people are missing!"

Hence, the Torah says, “Moses and the children of Israel will sing,” in the future tense. Moses explained to his people, that the story is far from over. The Jews in Egypt have died, but their souls are alive, and they will return during the resurrection of the dead. We can sing now, said Moses, not because there is no pain, but because despite the pain, we do not believe we have seen the end of the story. We can celebrate the future.

Future and Past

This is what sets apart Jewish history. All of history is, by definition, a study of the past. Jewish history alone is unique. It is a story of the past based on the future. For the Jewish people, history is defined not only by the past but also by the future. Since we know that redemption will come, we go back and redefine exile as the catalyst for redemption and healing.

For the Jewish people, the future defines and gives meaning to the past.

With this, the Belzer Rebbe inspired his students to begin singing yet again as they arrived at the soil of the Holy Land, on Shabbos Beshalach 1944, 80 years ago.

His disciples did sing. And if you visit the main Belz synagogue in Jerusalem, you can hear thousands of Jews, young and old, singing and celebrating Jewish life.

Sunrise

I once read an article by a survivor of Auschwitz. He related how every morning, as the sun rose over Auschwitz, his heart would swell with anger. How dare you?! How can the sun be so indifferent to the suffering of millions and just rise again to cast its warm glow on a world drenched in the blood of the purest and holiest? How can the sun be so cruel and apathetic? Where was the protest?

But, he continued his story, he survived. I came out of the hell. And the day after liberation, as I lay in a bed for the first time in years, I watched the sunrise. For the first time, I felt so grateful for the sun. I felt empowered that after the long night, which seemed to never end, light has at last arrived.

This is the story of our people. Our sun has set. But our sun will also rise. Life, love, and hope will prevail. “Netzach Yisroel Lo Yishaker,” the Eternal One of Israel does not lie. There will be an end to the night. “Moses and the children of Israel will sing.”

And the singing can begin now. We will see Moshiach very very soon -- may it be NOW!

__________________

[1] Exodus 14:15.

[2] The story is recorded in the book “B’kdushaso Shel Aaron,” page 436.

[3] Mechilta and Rashi Exodus 13:2

Tags

Categories

Essay Parshas Beshalach

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 25, 2024

- |

- 15 Sh'vat 5784

- |

- 7015 views

Elkana Vizel's Last Letter

Jewish History Is a Study of the Future: “Moses and the Children of Israel Will Sing”

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- January 25, 2024

Elkanah Vizel

Before heading into battle, Master Sgt. Elkana Vizel, 35, penned a letter for his loved ones. At his funeral this week, his widow read the letter.

The father of four young children, Rabbi Elkana Vizel was among 21 reservists killed last Monday night in Northern Gaza.

Despite sustaining injuries in Operation Protective Edge and having the choice to stay out of combat service, Elkana opted to enlist in the reserves, dedicating himself to defending his people. In his heartfelt letter to his loved ones, he expressed unwavering conviction in his decision to return to the frontlines. Here is what he wrote:

If you are reading these words, something must have happened to me. If I was kidnapped, I demand that no deal be made for the release of any terrorist to release me. Our overwhelming victory is more important than anything, so please continue to work with all your might so that the victory is as overwhelming as possible.

Maybe I fell in battle. When a soldier falls in battle, it is sad, but I ask you to be happy. Don't be sad when you part with me. Touch hearts, hold each other's hands, and strengthen each other. We have so much to be proud and happy about.

We are writing the most significant moments in the history of our nation and the entire world. So please, be happy, be optimistic, keep choosing life all the time. Spread love, light, and optimism. Look at your loved ones in the whites of their eyes and remind them that everything we go through in this life is worth it and we have something to live for.

Don't stop the power of life for a moment. I was already wounded in Operation Tzuk Eitan, but I do not regret that I returned to fight. This is the best decision I ever made.

We have no words to describe the nobility, love, purity and holiness of our soldiers and our brothers and sisters fighting for their life. Elkana's letter brought back a story and message that transpired 80 years ago, in one of the darkest moments of our history.

Future Tense

"That day, G-d saved Israel from the hands of the Egyptians . . . The Israelites saw the great power G-d had displayed against the Egyptians, and the people were in awe of G-d. They believed in G-d and in his servant Moses. Moses and the Israelites then sang this song, saying…"[1]

The Song at the Sea was one of the great epiphanies of history. The sages said that even the humblest of Jews saw at that moment what even the greatest of prophets was not privileged to see. For the first time, they broke into a collective song—a song we recite every day during the morning prayers.

Yet, as is often the case, the English translation does not capture all of the nuances. In the original text, the Torah states:

Then Moses and the children of Israel will sing this song to the Lord, and they spoke, saying, I will sing to the Lord, for very exalted is He; a horse and its rider He cast into the sea.

בשלח טו, א: אָ֣ז יָשִֽׁיר־משֶׁה֩ וּבְנֵ֨י יִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ לַֽיהֹוָ֔ה וַיֹּֽאמְר֖וּ לֵאמֹ֑ר אָשִׁ֤ירָה לַּֽיהֹוָה֙ כִּֽי־גָאֹ֣ה גָּאָ֔ה ס֥וּס וְרֹֽכְב֖וֹ רָמָ֥ה בַיָּֽם:

It speaks of Moses’ and the Jews’ singing, in the future tense. This is profoundly strange. The Torah is relating a story that occurred in the past, not one that will occur in the future. It seems like a “bad grammatical error.”

The sages, quoted by Rashi, offer a fascinating insight:

סנהדרין צא, ב: תניא אמר רבי מאיר מניין לתחיית המתים מן התורה שנאמר (שמות טו, א) אז ישיר משה ובני ישראל את השירה הזאת לה', שר לא נאמר אלא ישיר מכאן לתחיית המתים מן התורה.

One of the principles of the Jewish faith is the belief in Techiyas Hamesim, the resurrection of the dead, following the messianic era. Death is not the end of the story. The soul continues to live and exist, spiritually. What is more, the soul will return back to a body.

This is why the Torah chooses to describe the song in the future tense: Moses and his people will indeed sing in the future, after the resurrection. Their song was not only a story of the past; it will also occur in the future.

While this is a fascinating idea, it still begs the question: Why does the Torah specifically hint to the future resurrection here, as opposed to any other place in the Torah? And why will Moses and Israel sing in the future as well?

After the War

The following story happened on this very Shabbos, 80 years ago.[2]

One of the great rabbis of Pre-war Europe was Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880 – 1957), the fourth Rebbe of the Belz Chasidic dynasty (Belz is a city in Galicia, Poland.) He led the movement from 1926 until his death in 1957.

Known for his piety and saintliness, Reb Aharon of Belz was called the "Wonder Rabbi" by Jews and gentiles alike for the miracles he performed. He barely ate or slept. He was made of “spiritual stuff.” (The Lubavitcher Rebbe once visited him in Berlin, and described him as “tzurah bli chomer,” energy without matter.)

His reign as Rebbe saw the devastation of the Belz community, along with most of European Jewry during the Holocaust. During the war, Reb Aharon was high on the list of Gestapo targets as a high-profile Rebbe. They murdered his wife and each of his children and grandchildren. He had no one left. With the support and financial assistance of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe in the US, and Belzer Chasidim in Israel, England, and the United States, he and his half-brother, Rabbi Mordechai of Bilgoray, managed to escape from Poland into Hungary, then into Turkey, Lebanon, and finally into Israel, in February 1944. He remarried but had no children.

Most thought that Belz was an item of history. Yet, the impossible occurred. His half-brother Rabbi Mordechai also remarried and had a son, then died suddenly a few months later. Reb Aharon raised his half-brother's year-old son, Yissachar Dov, and groomed him to succeed him as Belzer Rebbe. Today, it is one of the largest Chassidic groups in Israel, numbering more than 50,000, with hundreds of institutions, schools, synagogues, and yeshivos.

The Belzer Rebbe not once said any of the prescribed prayers like Yizkor or Kaddish for his wife and children, because he felt that those who had been slain by the Nazis for being Jews were of transcendent holiness; their spiritual stature was beyond our comprehension. Any words about them that we might utter were irrelevant and perhaps even a desecration of their memory.

For Reb Aharon, the only proper way to respond to the near-destruction of Belz and honor the memory of the dead was to build new institutions and slowly nurture a new generation of Chasidim. This is what he did for the remainder of his life. He settled in secular Zionist Tel Aviv, and not in the more religious Jerusalem because, he said, it is the only city without a Church or Mosque.

The First Shabbos

The first Shabbos after he arrived in Israel during the winter of 1944 was Shabbos Parshas Beshalach, and he spent it in Haifa. He was alone in the world, without a single relative (save his brother) alive.

During the Shabbos, he held a “tisch,” a formal Chassidic gathering, in which Chassidim sing, dance, and share words of inspiration and Torah. The Belzer Rebbe quickly realized that the Holocaust survivors present, who had endured indescribable suffering and had lost virtually everything they had, were in no mood of singing. The Rebbe decided to address himself and his few broken Chassidim who had survived.

The Belzer Rebbe raised the above question of why the Torah specifically alludes to techiyas hameisim, the resurrection of the dead, in conjunction with the song that was sung celebrating the splitting of the Red Sea?

He gave this chilling answer. When the Jewish people sang the Song of the Sea, much of the nation was not present. How many people did not survive the enslavement of Egypt? How many Jewish children were drowned in the Nile? How many Jews never lived to see the day of the Exodus? How many refused to embark on a journey into the unknown?

According to tradition, only a fifth of the Jewish people made it out.[3] 80% of the Jews died in Egypt. It is safe to say that everyone who did make it out of Egypt had lost relatives and could not fully rejoice in the miracles they were witnessing. Now, the sea split. The wonder of wonders. Moses says to them, “It is time to sing." But they responded, "Sing? How can we sing? Eighty percent of our people are missing!"

Hence, the Torah says, “Moses and the children of Israel will sing,” in the future tense. Moses explained to his people, that the story is far from over. The Jews in Egypt have died, but their souls are alive, and they will return during the resurrection of the dead. We can sing now, said Moses, not because there is no pain, but because despite the pain, we do not believe we have seen the end of the story. We can celebrate the future.

Future and Past

This is what sets apart Jewish history. All of history is, by definition, a study of the past. Jewish history alone is unique. It is a story of the past based on the future. For the Jewish people, history is defined not only by the past but also by the future. Since we know that redemption will come, we go back and redefine exile as the catalyst for redemption and healing.

For the Jewish people, the future defines and gives meaning to the past.

With this, the Belzer Rebbe inspired his students to begin singing yet again as they arrived at the soil of the Holy Land, on Shabbos Beshalach 1944, 80 years ago.

His disciples did sing. And if you visit the main Belz synagogue in Jerusalem, you can hear thousands of Jews, young and old, singing and celebrating Jewish life.

Sunrise

I once read an article by a survivor of Auschwitz. He related how every morning, as the sun rose over Auschwitz, his heart would swell with anger. How dare you?! How can the sun be so indifferent to the suffering of millions and just rise again to cast its warm glow on a world drenched in the blood of the purest and holiest? How can the sun be so cruel and apathetic? Where was the protest?

But, he continued his story, he survived. I came out of the hell. And the day after liberation, as I lay in a bed for the first time in years, I watched the sunrise. For the first time, I felt so grateful for the sun. I felt empowered that after the long night, which seemed to never end, light has at last arrived.

This is the story of our people. Our sun has set. But our sun will also rise. Life, love, and hope will prevail. “Netzach Yisroel Lo Yishaker,” the Eternal One of Israel does not lie. There will be an end to the night. “Moses and the children of Israel will sing.”

And the singing can begin now. We will see Moshiach very very soon -- may it be NOW!

__________________

[1] Exodus 14:15.

[2] The story is recorded in the book “B’kdushaso Shel Aaron,” page 436.

[3] Mechilta and Rashi Exodus 13:2- Comment

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein in honor of Sholom Yosef Gavriel ben Maya Tifcha, Gavriel Nash.

Dedicated by Yisroel Yitzchak HaKohain Kaplan in honor of Yud Shevat and the 74th yartzeit of the Previous Rebbe and in honor of our brave soldiers.

Dedicated by Charline Rubinstein In memory of her father, Rabbi Yaakov ben Moshe Masoud Nezri z"l, grandson of Rabbi Yitzhak Abihsera, and her brother, Abba ben Moshe Masoud Nezri z"l

Class Summary:

As is often the case, the English translation does not capture all of the nuances of the original text. The Torah states: “Then Moses and the children of Israel will sing this song to the Lord…” This is strange. The Torah is relating a story that occurred in the past, not one that will occur in the future. It seems like a grammatical error.

The sages, quoted by Rashi, offer a fascinating insight: One of the principles of Jewish faith is the belief in Techiyas Hamesim, the resurrection of the dead, following the messianic era. It is the notion that death is not the end of the story. This is why the Torah chooses to describe the song in the future tense: Moses and his people will indeed sing in the future, after the resurrection. Their song was not only a story of the past; it will also occur in the future.

While this is a fascinating idea, it still begs the question: Why does the Torah specifically hint to the future resurrection here as opposed to any other place in the Torah?

I wish to share with you a story that happened on this very Shabbos, more than seven decades ago. One of the great rabbis of Pre-war Europe was Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880–1957), the fourth Rebbe of the Belz Chasidic dynasty. He led the movement from 1926 until his death in 1957. Known for his piety and mysticism, Reb Aharon was called the "Wonder Rabbi" by Jews and gentiles alike for the miracles he performed. He barely ate or slept. He was made of “spiritual stuff.”

He lost his entire family and most of his followers in the war. When he escaped and made it to Israel in February 1944, he spent his first Shabbos, Parshat Beshalach, in Haifa. After the horrible pain they endured, nobody was in the mood of singing. And the Belzer Rebbe shared an incredible insight into the nature of Jewish history. “Moshe will sing.”

Please help us continue our work

Sign up to receive latest content by Rabbi YY

Join our WhatsApp Community

Join our WhatsApp Community

Please leave your comment below!