The Lame Leading the Blind

The Kabbalah of Chess

- March 7, 2011

- |

- 1 Adar II 5771

Rabbi YY Jacobson

1603 צפיות

The Lame Leading the Blind

The Kabbalah of Chess

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 7, 2011

A Tale of Two Pilots

One day at a busy airport, the passengers on a commercial airliner are seated, waiting for the cockpit crew to show up so they can get underway. The pilot and co-pilot finally appear in the rear of the plane and begin walking up to the cockpit through the center aisle. Both appear to be blind.

The pilot is using a white cane, bumping into passengers right and left as he stumbles down the aisle, and the co-pilot is using a guide dog. Both have their eyes covered with huge sunglasses. At first, the passengers don't react, thinking that it must be some sort of practical joke. However, after a few minutes, the engines start revving and the airplane starts moving.

The passengers look at each other with some uneasiness, whispering among themselves and looking desperately to the stewardesses for reassurance. Then the airplane starts accelerating rapidly down the runway and people begin panicking. Some passengers are praying, and as the plane gets closer and closer to the end of the runway, the voices are becoming more and more hysterical. Finally, when the airplane has less than 20 feet of runway left, and about to plunge into the water, there is a sudden change in the pitch of the shouts as everyone screams at once, and at the very last moment, the airplane lifts off and is airborne.

Up in the cockpit, the co-pilot breathes a sigh of relief and turns to the pilot: "You know, one of these days the passengers aren't going to scream, and we're gonna go straight into the water and die!"

The Orchard

The Midrash is intrigued by the statement in this week’s Torah portion, Vayikra: “When a soul (nefesh) sins.”[1] Not “when a person sins,” but “when a soul sins.” Is it the soul who sins?

Says the Midrash[2]: Rabbi Yishmael taught: this is comparable to a king who has an orchard of prime figs. He appoints two watchmen, one was lame, and the other was blind, entrusting them with his orchard. After a while, the lame turns to the blind and says, “I see such delicious fruit in this vineyard!” And the blind man replies, “So let us eat.”

“But can I walk?!”

“And can I see?!”

So the lame man rode on the back of the blind man, and together they reached and ate the fruit, and then returned to their positions.

After a while, the king enters his orchard. He asks them, “Where is my beautiful fruit?”

The blind man says, “O king, how can I have eaten them? I can't see!” And the lame man says, “O king, can I walk? How can I have reached them?”

The king was wise, what did he do? He hoisted the lame man on the back of the blind man and had them walk together, saying “This is how you ate my figs.”

Just so, in the future day of reckoning, G-d will ask the soul, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the soul will reply, “Master of the Universe! I did not sin, the body sinned! Behold! From the moment I departed him I am like a pure bird, soaring towards heaven. How have I sinned?” So G-d will say to the body, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the body will reply, “Master of the Universe! I have not sinned, the soul sinned! Behold! From the moment the soul departed, I am lifeless as a stone cast upon the earth! How can I have sinned before you?”

What does G-d do? He brings the soul, casts it into the body, and cleanses them together, as it is written, [3]He shall call to the heavens above -- this is the soul -- and to the earth -- this is the body -- to judge His people.

Who Needs the Metaphor?

The Midrash is explaining that sin is only possible through a full and working collaboration between the body and the soul. The body can get things done, but it is directionless; the soul gives direction but it is aloof and “lame”—spiritual and ethereal. Together, they can achieve their goals: they can transgress together, and they can perform good deeds together. Yet the questions should be asked: The objective of allegories in the Torah is to clarify an otherwise difficult concept. Yet the point in this Midrash seems to be straightforward and simple: The body on its own is a corpse; the soul on its own is heavenly. Together, they create the reality we call “the human being.” Why the need for the elaborate metaphor of the blind and the lame in an orchard to explain the concept?The truth is, however, that this metaphor explains to us not only that the body and soul need each other, but also the very nature of the body and the soul and why they so desperately need each other.

The Capacity for Revolution

The body is represented by the blind man. Blinded by material reality, on its own, it is oblivious to the existence of transcendent oneness, to G-d. It subscribes to a “what you see is what you get” interpretation of existence; it is unable to see beyond its temporal perspective; it is unable to ever perceive or identify truth. It can't even see electricity, never mind the Divine electricity of life. And the worst type of blindness is the blindness of the one who thinks he can see.But the soul can see. She is intimately aware of the higher realities of life; she is not fooled by the illusion of materialism and consumerism.

On the other hand, the body can walk, while the soul is immobile. This is one of the great paradoxes of life: Because the soul can see, it is rendered “lame” and immobile. In the face of stark truth there is no room for mistakes, hence no room for decisions. If there is no decision-making, if there is no challenge or struggle, then there is no growth, no real movement. The soul, because it is so intensely aware of the truth, and because it is so perfect, is “stuck” in its orbit. Growth depends on the catalyst of failure, of imperfection. Only if you are capable of falling very low are you capable of climbing very high.

The body, because of its blindness, knows how to walk, and run. In the words of King Solomon: “I returned and saw under the sun, that the race does not belong to the swift, nor the war to the mighty; neither do the wise have bread, nor do the understanding have riches.” [4] In its ignorance, the body is susceptible to fall and rise, to struggle and persevere, to learn from its mistakes, and grow. And it teaches the soul the secret of growth. Before that, it was on autopilot, robotic and consistent as the angels, and therefore stagnant.

The Story of Sam Reshevsky

Samuel Herman (Sammy) Reshevsky (1911-1992) was a famous chess prodigy and later a leading American chess Grandmaster. He was a contender for the World Chess Championship from about the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s; coming equal third in the World Chess Championship 1948 tournament, and equal second in the 1953 Candidates Tournament. He was also an eight-time winner of the U.S. Chess Championship.

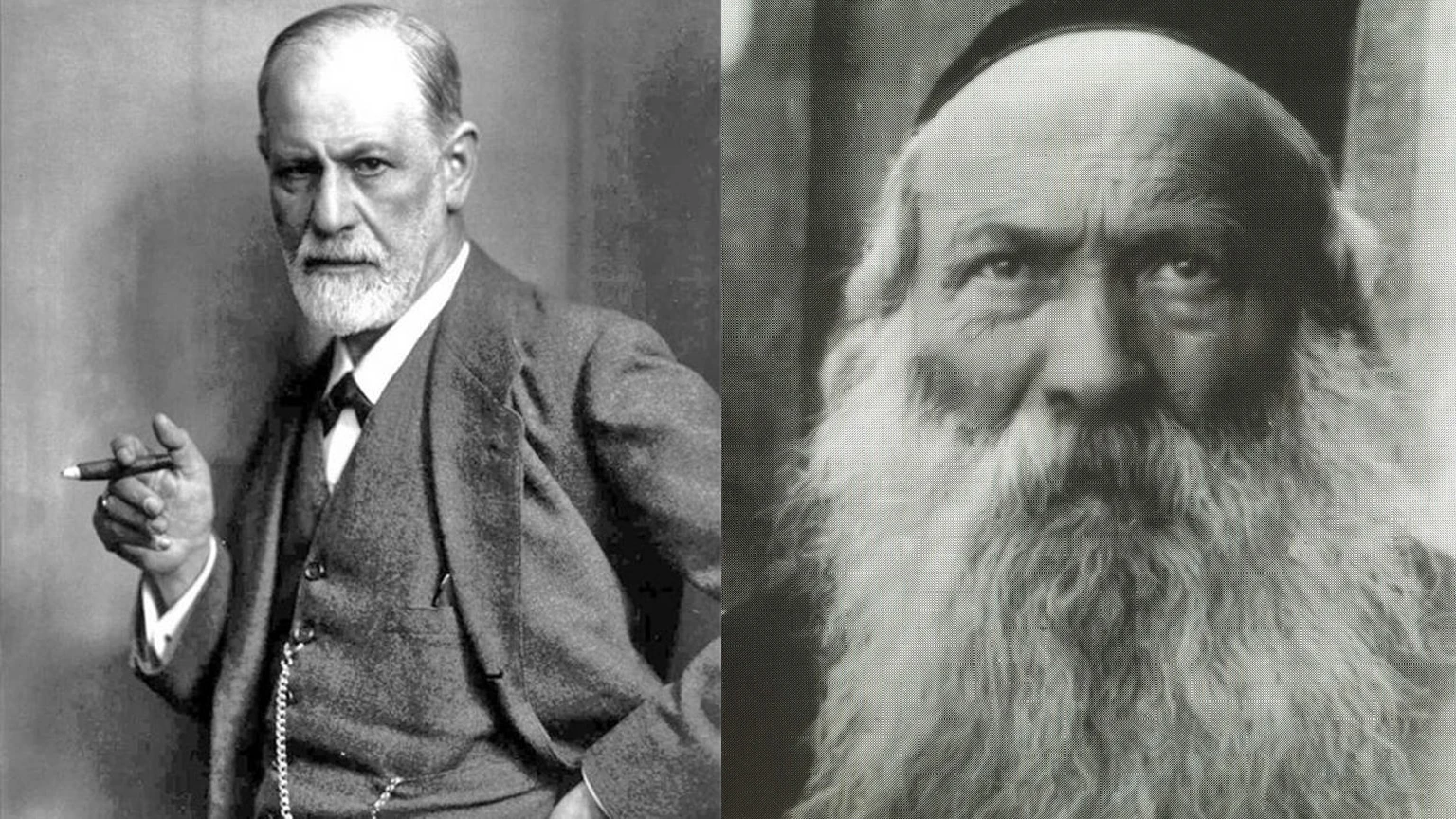

At the age of six, he would play against as many as 30 players at a time, moving quickly from board to board and could repeat all 30 games afterwards, move by move. He was known as "Shmulik der vunder kind”—Shmuel the wonder child. He was a descendant of Rabbi Yonasan Eibshitz, who descended from the great Kabalist, Rabbi Isaac Luria, the Arizal.

Sammy Reshevsky grew up in an observant home, and throughout his life and fame, remained faithful to his Judaism and Torah, refusing to ever play chess on the Sabbath or Holidays. Upon turning 70 and no longer on top of his game, he asked the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schnnersohn, if he should retire. The Rebbe advised him to continue playing because it was a “Kiddush Hashem”—a proud demonstration of a Jew succeeding without compromising his spiritual ideals and values. Reshevsky complied and shortly afterward, he traveled to Russia and upset the world champion, Vassily Smyslov.

An interesting tidbit: in 1984, the Lubavitcher Rebbe sent Sammy Reshevsky to California to try and help his colleague Bobby Fischer get out of his world-famous depression and isolation.

Living in Crown Heights in the 1940’s, Sammy prayed in the central Lubavitch synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, NY. Once, at a Sabbath gathering (farbrengen in Yiddish), in 1948, the Rebbe, in recognition of his presence, explained the spiritual meaning behind the chess game.

The Chess Game

There is one king. All of the other pieces revolve around him and their entire mission is to protect and serve him. G-d is the King, all else was created by Him, given the opportunity to connect to His truth and to serve Him.

The queen represents the feminine manifestation of the divine, known as the “shechinah,” intimately involved with every aspect of creation, granting vitality and substance to every existence. The queen is the most practically effective piece, often sent into the lines of fire, even placed in danger. Likewise, G-d risks His own dignity, as it were, by investing Himself in every creature and existence, subjecting Himself to the vicissitudes of the human condition.

Then there are bishops, rooks, and knights. They are swift, free, not limited by the squares immediately surrounding them; they can “fly” around freely, without constraints. These are symbolic of the angels—in their three mystical categories we discuss in the daily morning services, “seraphim,” “chayos” and “ofanim,” represented by the bishops, rooks, and knights.

In order for there to be free choice in the world, there are two teams, the white and the black. One team representing G-dliness and holiness; the other team representing everything antithetical to G-dliness and holiness. The teams are engaged in a fierce battle. And for the confrontation to be meaningful each team contains, at least on the surface, all the properties contained in the opposite team. Both teams pretend to have a king, queen, bishops, rooks, and knights.

Finally, there are the pawns. They are very limited in their travel, moving only one step at a time, only in a singular direction, and they constantly get “knocked off.” But when they fight through the “board,” arriving at their destination, they can be promoted even to the rank of the queen, something that the bishop, rook, or knight can never achieve.

The Pawn represents the human being living down here on earth. We, humans, take very small steps, and we are so limited in every aspect of our journey and our growth. We also constantly make mistakes and get “knocked down.” But when man perseveres and overcomes the angst and despair of his or her own failings and mortality; when we fight the fight to subdue darkness and to reveal the presence of the “king” within our own bodies, our own psyches and the world around us—the human being surpasses even angels; the pawn is transformed into a queen! The human life reunites with its source above, the queen, the Shechinah, experiencing the deepest intimacy with the King Himself.

The bishops, rooks, and knights, though spiritually powerful and angelic, are predictable, and limited by their role. There is no room for real promotion, no substantive growth, no radical progression. Yes, they fly around, but only within their own orbit. The angels on high, as well as the soul alone on high, before entering the body, are powerful yet confined by their own spiritual standing. It is the limitations of the human person that stimulate his or her deepest growth. The limits of our existence create friction, causing us to strain against the trials and disappointments of life.

Embracing the Difficult Marriage

So the body and soul can choose to accept their natural schizophrenia, as a victim, with each blaming the other for its faults, shirking responsibility and duty. Or they can choose to embrace the challenges and opportunities this existential conflict provides, taking the sight, clarity, and vision of the soul and harnessing it to the mobility and energy of the body.

This, then, is the message behind the midrashic metaphor of the lame and the blind watching the orchard of the king. When the lame soul leads the blind body, the blind body can raise to lame soul to unimaginable heights.[5]

(Please make even a small and secure contribution to help us continue the wisdom & inspiration. Click here.)

[1] Leviticus 4:2

[2] Vayikra Rabba 4:5. The same idea is in Talmud Sanhedrin 91b

[3] Psalms 50:4

[4] Ecclesiastes 9:11

[5] This essay is based on Torah Or Parshas Vayeishev. Sefas Emes Vayikra 5647. Toras Yemei Berieshis, 5708 (1948.)

My thanks to Rabbi Avi Shlomo for his help in writing and preparing this essay.

- תגובה

סיכום השיעור:

The Lame Leading the Blind - The Kabbalah of Chess

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein, in the loving memory of Alta Shula Swerdlov. And in honor of their daughter, Yetta Alta Shula, "Aliyah" Schottenstein.

A Tale of Two Pilots

One day at a busy airport, the passengers on a commercial airliner are seated, waiting for the cockpit crew to show up so they can get underway. The pilot and co-pilot finally appear in the rear of the plane and begin walking up to the cockpit through the center aisle. Both appear to be blind.

The pilot is using a white cane, bumping into passengers right and left as he stumbles down the aisle, and the co-pilot is using a guide dog. Both have their eyes covered with huge sunglasses. At first, the passengers don't react, thinking that it must be some sort of practical joke. However, after a few minutes, the engines start revving and the airplane starts moving.

The passengers look at each other with some uneasiness, whispering among themselves and looking desperately to the stewardesses for reassurance. Then the airplane starts accelerating rapidly down the runway and people begin panicking. Some passengers are praying, and as the plane gets closer and closer to the end of the runway, the voices are becoming more and more hysterical. Finally, when the airplane has less than 20 feet of runway left, and about to plunge into the water, there is a sudden change in the pitch of the shouts as everyone screams at once, and at the very last moment, the airplane lifts off and is airborne.

Up in the cockpit, the co-pilot breathes a sigh of relief and turns to the pilot: "You know, one of these days the passengers aren't going to scream, and we're gonna go straight into the water and die!"

The Orchard

The Midrash is intrigued by the statement in this week’s Torah portion, Vayikra: “When a soul (nefesh) sins.”[1] Not “when a person sins,” but “when a soul sins.” Is it the soul who sins?

Says the Midrash[2]: Rabbi Yishmael taught: this is comparable to a king who has an orchard of prime figs. He appoints two watchmen, one was lame, and the other was blind, entrusting them with his orchard. After a while, the lame turns to the blind and says, “I see such delicious fruit in this vineyard!” And the blind man replies, “So let us eat.”

“But can I walk?!”

“And can I see?!”

So the lame man rode on the back of the blind man, and together they reached and ate the fruit, and then returned to their positions.

After a while, the king enters his orchard. He asks them, “Where is my beautiful fruit?”

The blind man says, “O king, how can I have eaten them? I can't see!” And the lame man says, “O king, can I walk? How can I have reached them?”

The king was wise, what did he do? He hoisted the lame man on the back of the blind man and had them walk together, saying “This is how you ate my figs.”

Just so, in the future day of reckoning, G-d will ask the soul, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the soul will reply, “Master of the Universe! I did not sin, the body sinned! Behold! From the moment I departed him I am like a pure bird, soaring towards heaven. How have I sinned?” So G-d will say to the body, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the body will reply, “Master of the Universe! I have not sinned, the soul sinned! Behold! From the moment the soul departed, I am lifeless as a stone cast upon the earth! How can I have sinned before you?”

What does G-d do? He brings the soul, casts it into the body, and cleanses them together, as it is written, [3]He shall call to the heavens above -- this is the soul -- and to the earth -- this is the body -- to judge His people.

Who Needs the Metaphor?

The Midrash is explaining that sin is only possible through a full and working collaboration between the body and the soul. The body can get things done, but it is directionless; the soul gives direction but it is aloof and “lame”—spiritual and ethereal. Together, they can achieve their goals: they can transgress together, and they can perform good deeds together. Yet the questions should be asked: The objective of allegories in the Torah is to clarify an otherwise difficult concept. Yet the point in this Midrash seems to be straightforward and simple: The body on its own is a corpse; the soul on its own is heavenly. Together, they create the reality we call “the human being.” Why the need for the elaborate metaphor of the blind and the lame in an orchard to explain the concept?

The truth is, however, that this metaphor explains to us not only that the body and soul need each other, but also the very nature of the body and the soul and why they so desperately need each other.

The Capacity for Revolution

The body is represented by the blind man. Blinded by material reality, on its own, it is oblivious to the existence of transcendent oneness, to G-d. It subscribes to a “what you see is what you get” interpretation of existence; it is unable to see beyond its temporal perspective; it is unable to ever perceive or identify truth. It can't even see electricity, never mind the Divine electricity of life. And the worst type of blindness is the blindness of the one who thinks he can see.

But the soul can see. She is intimately aware of the higher realities of life; she is not fooled by the illusion of materialism and consumerism.

On the other hand, the body can walk, while the soul is immobile. This is one of the great paradoxes of life: Because the soul can see, it is rendered “lame” and immobile. In the face of stark truth there is no room for mistakes, hence no room for decisions. If there is no decision-making, if there is no challenge or struggle, then there is no growth, no real movement. The soul, because it is so intensely aware of the truth, and because it is so perfect, is “stuck” in its orbit. Growth depends on the catalyst of failure, of imperfection. Only if you are capable of falling very low are you capable of climbing very high.

The body, because of its blindness, knows how to walk, and run. In the words of King Solomon: “I returned and saw under the sun, that the race does not belong to the swift, nor the war to the mighty; neither do the wise have bread, nor do the understanding have riches.” [4] In its ignorance, the body is susceptible to fall and rise, to struggle and persevere, to learn from its mistakes, and grow. And it teaches the soul the secret of growth. Before that, it was on autopilot, robotic and consistent as the angels, and therefore stagnant.

The Story of Sam Reshevsky

Samuel Herman (Sammy) Reshevsky (1911-1992) was a famous chess prodigy and later a leading American chess Grandmaster. He was a contender for the World Chess Championship from about the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s; coming equal third in the World Chess Championship 1948 tournament, and equal second in the 1953 Candidates Tournament. He was also an eight-time winner of the U.S. Chess Championship.

At the age of six, he would play against as many as 30 players at a time, moving quickly from board to board and could repeat all 30 games afterwards, move by move. He was known as "Shmulik der vunder kind”—Shmuel the wonder child. He was a descendant of Rabbi Yonasan Eibshitz, who descended from the great Kabalist, Rabbi Isaac Luria, the Arizal.

Sammy Reshevsky grew up in an observant home, and throughout his life and fame, remained faithful to his Judaism and Torah, refusing to ever play chess on the Sabbath or Holidays. Upon turning 70 and no longer on top of his game, he asked the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schnnersohn, if he should retire. The Rebbe advised him to continue playing because it was a “Kiddush Hashem”—a proud demonstration of a Jew succeeding without compromising his spiritual ideals and values. Reshevsky complied and shortly afterward, he traveled to Russia and upset the world champion, Vassily Smyslov.

An interesting tidbit: in 1984, the Lubavitcher Rebbe sent Sammy Reshevsky to California to try and help his colleague Bobby Fischer get out of his world-famous depression and isolation.

Living in Crown Heights in the 1940’s, Sammy prayed in the central Lubavitch synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, NY. Once, at a Sabbath gathering (farbrengen in Yiddish), in 1948, the Rebbe, in recognition of his presence, explained the spiritual meaning behind the chess game.

The Chess Game

There is one king. All of the other pieces revolve around him and their entire mission is to protect and serve him. G-d is the King, all else was created by Him, given the opportunity to connect to His truth and to serve Him.

The queen represents the feminine manifestation of the divine, known as the “shechinah,” intimately involved with every aspect of creation, granting vitality and substance to every existence. The queen is the most practically effective piece, often sent into the lines of fire, even placed in danger. Likewise, G-d risks His own dignity, as it were, by investing Himself in every creature and existence, subjecting Himself to the vicissitudes of the human condition.

Then there are bishops, rooks, and knights. They are swift, free, not limited by the squares immediately surrounding them; they can “fly” around freely, without constraints. These are symbolic of the angels—in their three mystical categories we discuss in the daily morning services, “seraphim,” “chayos” and “ofanim,” represented by the bishops, rooks, and knights.

In order for there to be free choice in the world, there are two teams, the white and the black. One team representing G-dliness and holiness; the other team representing everything antithetical to G-dliness and holiness. The teams are engaged in a fierce battle. And for the confrontation to be meaningful each team contains, at least on the surface, all the properties contained in the opposite team. Both teams pretend to have a king, queen, bishops, rooks, and knights.

Finally, there are the pawns. They are very limited in their travel, moving only one step at a time, only in a singular direction, and they constantly get “knocked off.” But when they fight through the “board,” arriving at their destination, they can be promoted even to the rank of the queen, something that the bishop, rook, or knight can never achieve.

The Pawn represents the human being living down here on earth. We, humans, take very small steps, and we are so limited in every aspect of our journey and our growth. We also constantly make mistakes and get “knocked down.” But when man perseveres and overcomes the angst and despair of his or her own failings and mortality; when we fight the fight to subdue darkness and to reveal the presence of the “king” within our own bodies, our own psyches and the world around us—the human being surpasses even angels; the pawn is transformed into a queen! The human life reunites with its source above, the queen, the Shechinah, experiencing the deepest intimacy with the King Himself.

The bishops, rooks, and knights, though spiritually powerful and angelic, are predictable, and limited by their role. There is no room for real promotion, no substantive growth, no radical progression. Yes, they fly around, but only within their own orbit. The angels on high, as well as the soul alone on high, before entering the body, are powerful yet confined by their own spiritual standing. It is the limitations of the human person that stimulate his or her deepest growth. The limits of our existence create friction, causing us to strain against the trials and disappointments of life.

Embracing the Difficult Marriage

So the body and soul can choose to accept their natural schizophrenia, as a victim, with each blaming the other for its faults, shirking responsibility and duty. Or they can choose to embrace the challenges and opportunities this existential conflict provides, taking the sight, clarity, and vision of the soul and harnessing it to the mobility and energy of the body.

This, then, is the message behind the midrashic metaphor of the lame and the blind watching the orchard of the king. When the lame soul leads the blind body, the blind body can raise to lame soul to unimaginable heights.[5]

(Please make even a small and secure contribution to help us continue the wisdom & inspiration. Click here.)

[1] Leviticus 4:2

[2] Vayikra Rabba 4:5. The same idea is in Talmud Sanhedrin 91b

[3] Psalms 50:4

[4] Ecclesiastes 9:11

[5] This essay is based on Torah Or Parshas Vayeishev. Sefas Emes Vayikra 5647. Toras Yemei Berieshis, 5708 (1948.)

My thanks to Rabbi Avi Shlomo for his help in writing and preparing this essay.

תגים

קטגוריות

Essay Vayikra

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 7, 2011

- |

- 1 Adar II 5771

- |

- 1603 צפיות

The Lame Leading the Blind

The Kabbalah of Chess

Rabbi YY Jacobson

- March 7, 2011

A Tale of Two Pilots

One day at a busy airport, the passengers on a commercial airliner are seated, waiting for the cockpit crew to show up so they can get underway. The pilot and co-pilot finally appear in the rear of the plane and begin walking up to the cockpit through the center aisle. Both appear to be blind.

The pilot is using a white cane, bumping into passengers right and left as he stumbles down the aisle, and the co-pilot is using a guide dog. Both have their eyes covered with huge sunglasses. At first, the passengers don't react, thinking that it must be some sort of practical joke. However, after a few minutes, the engines start revving and the airplane starts moving.

The passengers look at each other with some uneasiness, whispering among themselves and looking desperately to the stewardesses for reassurance. Then the airplane starts accelerating rapidly down the runway and people begin panicking. Some passengers are praying, and as the plane gets closer and closer to the end of the runway, the voices are becoming more and more hysterical. Finally, when the airplane has less than 20 feet of runway left, and about to plunge into the water, there is a sudden change in the pitch of the shouts as everyone screams at once, and at the very last moment, the airplane lifts off and is airborne.

Up in the cockpit, the co-pilot breathes a sigh of relief and turns to the pilot: "You know, one of these days the passengers aren't going to scream, and we're gonna go straight into the water and die!"

The Orchard

The Midrash is intrigued by the statement in this week’s Torah portion, Vayikra: “When a soul (nefesh) sins.”[1] Not “when a person sins,” but “when a soul sins.” Is it the soul who sins?

Says the Midrash[2]: Rabbi Yishmael taught: this is comparable to a king who has an orchard of prime figs. He appoints two watchmen, one was lame, and the other was blind, entrusting them with his orchard. After a while, the lame turns to the blind and says, “I see such delicious fruit in this vineyard!” And the blind man replies, “So let us eat.”

“But can I walk?!”

“And can I see?!”

So the lame man rode on the back of the blind man, and together they reached and ate the fruit, and then returned to their positions.

After a while, the king enters his orchard. He asks them, “Where is my beautiful fruit?”

The blind man says, “O king, how can I have eaten them? I can't see!” And the lame man says, “O king, can I walk? How can I have reached them?”

The king was wise, what did he do? He hoisted the lame man on the back of the blind man and had them walk together, saying “This is how you ate my figs.”

Just so, in the future day of reckoning, G-d will ask the soul, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the soul will reply, “Master of the Universe! I did not sin, the body sinned! Behold! From the moment I departed him I am like a pure bird, soaring towards heaven. How have I sinned?” So G-d will say to the body, “Why have you sinned before me?” And the body will reply, “Master of the Universe! I have not sinned, the soul sinned! Behold! From the moment the soul departed, I am lifeless as a stone cast upon the earth! How can I have sinned before you?”

What does G-d do? He brings the soul, casts it into the body, and cleanses them together, as it is written, [3]He shall call to the heavens above -- this is the soul -- and to the earth -- this is the body -- to judge His people.

Who Needs the Metaphor?

The Midrash is explaining that sin is only possible through a full and working collaboration between the body and the soul. The body can get things done, but it is directionless; the soul gives direction but it is aloof and “lame”—spiritual and ethereal. Together, they can achieve their goals: they can transgress together, and they can perform good deeds together. Yet the questions should be asked: The objective of allegories in the Torah is to clarify an otherwise difficult concept. Yet the point in this Midrash seems to be straightforward and simple: The body on its own is a corpse; the soul on its own is heavenly. Together, they create the reality we call “the human being.” Why the need for the elaborate metaphor of the blind and the lame in an orchard to explain the concept?The truth is, however, that this metaphor explains to us not only that the body and soul need each other, but also the very nature of the body and the soul and why they so desperately need each other.

The Capacity for Revolution

The body is represented by the blind man. Blinded by material reality, on its own, it is oblivious to the existence of transcendent oneness, to G-d. It subscribes to a “what you see is what you get” interpretation of existence; it is unable to see beyond its temporal perspective; it is unable to ever perceive or identify truth. It can't even see electricity, never mind the Divine electricity of life. And the worst type of blindness is the blindness of the one who thinks he can see.But the soul can see. She is intimately aware of the higher realities of life; she is not fooled by the illusion of materialism and consumerism.

On the other hand, the body can walk, while the soul is immobile. This is one of the great paradoxes of life: Because the soul can see, it is rendered “lame” and immobile. In the face of stark truth there is no room for mistakes, hence no room for decisions. If there is no decision-making, if there is no challenge or struggle, then there is no growth, no real movement. The soul, because it is so intensely aware of the truth, and because it is so perfect, is “stuck” in its orbit. Growth depends on the catalyst of failure, of imperfection. Only if you are capable of falling very low are you capable of climbing very high.

The body, because of its blindness, knows how to walk, and run. In the words of King Solomon: “I returned and saw under the sun, that the race does not belong to the swift, nor the war to the mighty; neither do the wise have bread, nor do the understanding have riches.” [4] In its ignorance, the body is susceptible to fall and rise, to struggle and persevere, to learn from its mistakes, and grow. And it teaches the soul the secret of growth. Before that, it was on autopilot, robotic and consistent as the angels, and therefore stagnant.

The Story of Sam Reshevsky

Samuel Herman (Sammy) Reshevsky (1911-1992) was a famous chess prodigy and later a leading American chess Grandmaster. He was a contender for the World Chess Championship from about the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s; coming equal third in the World Chess Championship 1948 tournament, and equal second in the 1953 Candidates Tournament. He was also an eight-time winner of the U.S. Chess Championship.

At the age of six, he would play against as many as 30 players at a time, moving quickly from board to board and could repeat all 30 games afterwards, move by move. He was known as "Shmulik der vunder kind”—Shmuel the wonder child. He was a descendant of Rabbi Yonasan Eibshitz, who descended from the great Kabalist, Rabbi Isaac Luria, the Arizal.

Sammy Reshevsky grew up in an observant home, and throughout his life and fame, remained faithful to his Judaism and Torah, refusing to ever play chess on the Sabbath or Holidays. Upon turning 70 and no longer on top of his game, he asked the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schnnersohn, if he should retire. The Rebbe advised him to continue playing because it was a “Kiddush Hashem”—a proud demonstration of a Jew succeeding without compromising his spiritual ideals and values. Reshevsky complied and shortly afterward, he traveled to Russia and upset the world champion, Vassily Smyslov.

An interesting tidbit: in 1984, the Lubavitcher Rebbe sent Sammy Reshevsky to California to try and help his colleague Bobby Fischer get out of his world-famous depression and isolation.

Living in Crown Heights in the 1940’s, Sammy prayed in the central Lubavitch synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, NY. Once, at a Sabbath gathering (farbrengen in Yiddish), in 1948, the Rebbe, in recognition of his presence, explained the spiritual meaning behind the chess game.

The Chess Game

There is one king. All of the other pieces revolve around him and their entire mission is to protect and serve him. G-d is the King, all else was created by Him, given the opportunity to connect to His truth and to serve Him.

The queen represents the feminine manifestation of the divine, known as the “shechinah,” intimately involved with every aspect of creation, granting vitality and substance to every existence. The queen is the most practically effective piece, often sent into the lines of fire, even placed in danger. Likewise, G-d risks His own dignity, as it were, by investing Himself in every creature and existence, subjecting Himself to the vicissitudes of the human condition.

Then there are bishops, rooks, and knights. They are swift, free, not limited by the squares immediately surrounding them; they can “fly” around freely, without constraints. These are symbolic of the angels—in their three mystical categories we discuss in the daily morning services, “seraphim,” “chayos” and “ofanim,” represented by the bishops, rooks, and knights.

In order for there to be free choice in the world, there are two teams, the white and the black. One team representing G-dliness and holiness; the other team representing everything antithetical to G-dliness and holiness. The teams are engaged in a fierce battle. And for the confrontation to be meaningful each team contains, at least on the surface, all the properties contained in the opposite team. Both teams pretend to have a king, queen, bishops, rooks, and knights.

Finally, there are the pawns. They are very limited in their travel, moving only one step at a time, only in a singular direction, and they constantly get “knocked off.” But when they fight through the “board,” arriving at their destination, they can be promoted even to the rank of the queen, something that the bishop, rook, or knight can never achieve.

The Pawn represents the human being living down here on earth. We, humans, take very small steps, and we are so limited in every aspect of our journey and our growth. We also constantly make mistakes and get “knocked down.” But when man perseveres and overcomes the angst and despair of his or her own failings and mortality; when we fight the fight to subdue darkness and to reveal the presence of the “king” within our own bodies, our own psyches and the world around us—the human being surpasses even angels; the pawn is transformed into a queen! The human life reunites with its source above, the queen, the Shechinah, experiencing the deepest intimacy with the King Himself.

The bishops, rooks, and knights, though spiritually powerful and angelic, are predictable, and limited by their role. There is no room for real promotion, no substantive growth, no radical progression. Yes, they fly around, but only within their own orbit. The angels on high, as well as the soul alone on high, before entering the body, are powerful yet confined by their own spiritual standing. It is the limitations of the human person that stimulate his or her deepest growth. The limits of our existence create friction, causing us to strain against the trials and disappointments of life.

Embracing the Difficult Marriage

So the body and soul can choose to accept their natural schizophrenia, as a victim, with each blaming the other for its faults, shirking responsibility and duty. Or they can choose to embrace the challenges and opportunities this existential conflict provides, taking the sight, clarity, and vision of the soul and harnessing it to the mobility and energy of the body.

This, then, is the message behind the midrashic metaphor of the lame and the blind watching the orchard of the king. When the lame soul leads the blind body, the blind body can raise to lame soul to unimaginable heights.[5]

(Please make even a small and secure contribution to help us continue the wisdom & inspiration. Click here.)

[1] Leviticus 4:2

[2] Vayikra Rabba 4:5. The same idea is in Talmud Sanhedrin 91b

[3] Psalms 50:4

[4] Ecclesiastes 9:11

[5] This essay is based on Torah Or Parshas Vayeishev. Sefas Emes Vayikra 5647. Toras Yemei Berieshis, 5708 (1948.)

My thanks to Rabbi Avi Shlomo for his help in writing and preparing this essay.

- תגובה

Dedicated by David and Eda Schottenstein, in the loving memory of Alta Shula Swerdlov. And in honor of their daughter, Yetta Alta Shula, "Aliyah" Schottenstein.

סיכום השיעור:

The Lame Leading the Blind - The Kabbalah of Chess

שיעורים קשורים

אנא עזרו לנו להמשיך בפעילותנו

הרשמה לקבלת תוכן (באנגלית) עדכני מאת הרב יוסף יצחק ג'ייקובסון

צרפו חברים ומשפחה לקבוצת הווסטאפ שלנו

צרפו חברים ומשפחה לקבוצת הווסטאפ שלנו

אנא השאירו את תגובתכם למטה!